Creative provision of radiotherapy clinical placements

A shift towards digital clinical placements has shown significant learning growth

Therapeutic radiographers are a critical workforce group in oncology services. There is a need to grow the profession by 18% by 2025 to achieve the Cancer Workforce Plan target1.

Competing factors may negatively impact on this workforce ambition, for example, RePAIR findings report high levels of attrition for therapeutic radiography students in their second year of study2. More recently, the advent of a global pandemic has resulted in pre-registration students having varied experiences on their degree programmes, with many having interruptions to their clinical placements.

In 2020, Health Education England (HEE) committed to a £10m investment in a clinical placement expansion programme (CPEP) for nursing and allied health professionals3. In September 2020, The Christie Hospital NHS Foundation Trust accepted an investment through the CPEP funding stream. Working with multiple stakeholders, including all higher education institutions (HEIs) in England that delivery therapeutic radiography programmes, NHS England Proton Beam Service and NHS digital tenancy, the radiotherapy education team set out to design and implement a nationally accessible clinical placement to meet CPEP requirements, contributing to the training of our future radiotherapy workforce.

Clinical placement design

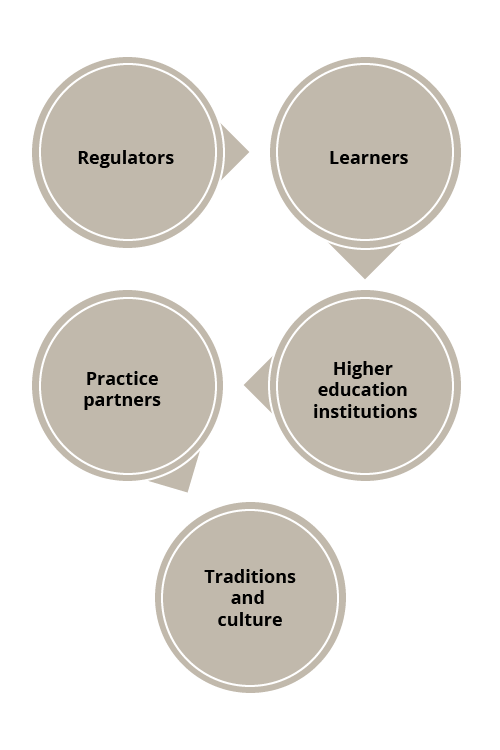

Quality provision of clinical placement activities are designed from multiple perspectives, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Stakeholder perspectives

An NHS Education Contract 2021-24 outlines a tripartite agreement between placement providers, education providers and HEE in terms of responsibilities and overarching governance for good practice, including high-quality learning environments where “learners acquire knowledge, information, comprehension or skill by study, instruction or experience in all fields of healthcare relevant to the programme”4.

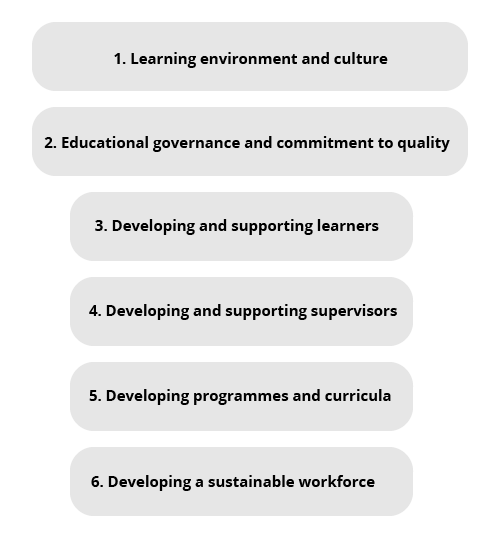

This contract is underpinned by the HEE Quality Framework (2021), articulating clinical learning environments as a whole system encompassing six core domains, illustrated in Figure 25.

Figure 2. HEE Quality Framework

A local CPEP project team was formed. Seven core members included a radiotherapy service transformation lead, head of digital services, clinical educationalist and clinical service subject matter experts (SMEs). Applying a RACI project tool, wider stakeholders were consulted or informed of project plans and progress6.

The main project aim was identified as: a national proton beam therapy blended clinical practice placement. Key objectives included:

- Widening accessibility for pre-registration learners on radiotherapy programmes.

- Promoting diversity and inclusivity.

- Maintaining biosecurity.

- Designing and delivering a modernised curriculum that includes highly technical radiotherapy modalities.

- Promoting multi-disciplinary working and learning across integrated care systems.

- Incorporating NHS leadership qualities and capabilities.

- Maintaining a clear line of sight to patient care experience and promotion of enhanced clinical outcomes.

- Shared learning, supported through a coaching model, enabling peer support and promoting practitioner self-regulation.

- Mapping the placement design against the College of Radiographers’ Education and Career Framework7, The Health and Care Professions Council Standards of Proficiency8 and the HEE Quality Framework5.

- Cost efficient, effective and sustainable in current and future clinical practice educational models.

Blended approach to

clinical practice placement

The creation of an effective clinical learning environment is complex and multifaceted. It is fundamental for both the teacher/supervisor and the learner to cultivate a safe space that promotes both physical and psychological security to enhance learning. Having access to expertise, role models, collaborative activities, time for discussion and deep reflection promotes learning. Information delivered sequentially and building knowledge in an orderly fashion promotes understanding and brings curiosity to the clinical conversation.

In a physical clinical setting, the added value of the patient and carer presence adds elements of “the unknown” and “unpredictability” to clinical scenarios, promoting professional adaptability, problem solving, communication and teamwork. Physical placements unquestionably mirror “real world” practice and encompass all the challenges that our autonomous practitioners face in their daily working lives.

The design of the proton beam blended placement used technology to co-create a virtual clinical placement. This provided an opportunity for students to gain insight into radiotherapy pathways from a systems leadership lens – they gained greater insights into clinical decision making, formulating their knowledge in a sequential order through a spiral clinical curriculum, informed by SME practitioners at the cutting edge of care.

Technology helps bring together local experts and students from across the country, enabling clinical conversations to be constructed and facilitated with support from local clinical educators. Students were offered frequent opportunities to deconstruct understanding and beliefs, reframe new ideas and notions to enhance their practice and that of their peers.

Front loading students with critical information regarding care episodes that they will witness in a physical environment provides a unique opportunity to socialise students in a safe and effective way, preparing students for their clinical learning and exposure to the “real world”. This environment also manages student vulnerability and promotes self-care and wellbeing by acknowledging thoughts and feelings that may be experienced in practice.

Digital alone and physical placements

Digital clinical placements alone provide unique and novel opportunities for SMEs to hold a clinical conversation in a virtual space. Students describe this as “a series of Ted Talks”. The platform, when structured appropriately, cultivates a safe and effective medium to hold clinical conversations, exploration and clinical reasoning. The platform promotes the diversity of clinical practice experiences to be shared and critically evaluated. The platform promotes time, space and activities to reconstruct and reframe clinical reasoning and critical decision making.

The digital environment, in effect, provides permission for students to think and make connections between their learning and its application. Removing a focus on task-orientated priorities (such as technical set up), the students are provided with wider professional growth in a range of professional capabilities essential to their profession.

In highly specialised clinical services, such as proton beam therapy, a physical clinical placement would not be feasible to all pre-registration students in England due to a lack of capacity. In addition, disparity across students would emerge, such as a need to travel and stay in Manchester with additional associated costs. A digital placement tackles such inequalities, promoting inclusivity.

Figure 3. Digital learners, cohort 4, February 2022

Front loading students with critical information regarding their practice placement allocation in a safe and meaningful space unequivocally impacts on the performance of those students who arrive at a clinical site. Students report safety in “already knowing what to expect” and feel motivated to connect their learning to lived experiences. Students have reported this as “the icing on the cake” and refer to meeting their colleagues as “meeting celebrities”. Students report a sense of “privilege, motivation and excitement” to connect learning and adapt to their new clinical surroundings.

The critical challenge

The NHS Long Term Plan reflects the pace of medical advancements, changing health needs and societal expectations, reflecting new models of care delivered by staff with the right skills, values and behaviours9. Arguably, aligned with this, opportunities to educate our future workforce in clinical practice will require remodelling. Traditions and culture within the “what, when and how” we educate and assess our future workforce are open to scrutiny, with opportunities to re-evaluate how students will be supported in the best way to improve clinical outcomes and care experiences for the populations they will serve.

Challenging the norms of physical clinical placement provision by introducing an effective medium to educate students outside of the “physical clinical space” has expectedly destabilised several stakeholders’ views of what clinical teaching and learning should represent.

A shift towards a clinical conversation in a virtual space is not a natural extension of teaching. All parties, including our clinical SMEs, learners and clinical educators, are required to review and reshape traditional ways of teaching and learning in the digital space.

A number of considerations are outlined in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Key considerations when creating a digital platform

The design of a virtual clinical placement has a significant advantage in terms of content and sequencing of learning compared with physical clinical placements.

In comparison to physical placements, a digital platform offers teaching and learning in an orderly and sequential format. Applying a spiral clinical curriculum, a learner’s knowledge is built from basic through to advanced concepts10. The learner is encouraged to draw on previous learning and apply to future scenarios to contextualise learning events and make connections. For example, we may consider the national eligibility criteria for patients offered a modality of radiotherapy and return to this at a later stage in the placement, with learners considering aligning service user expectations of treatments offered. Fundamentally, learners are encouraged to capture the “what” the “so what” and the “what next” when considering the impact of the topic of interest and clinical conversation, encouraging connections back to real-world scenarios.

To promote the construction of the clinical conversation, SMEs are encouraged and supported to create a “show and tell” narrative. Using storytelling, SMEs are able to illustrate their working environment and duties through a range of media and share stories of their personal and professional experiences. It is noted by learners that the vulnerabilities of experienced practitioners increase learner engagement and interest in topics. Stories with patients and carers at the heart of the clinical conversation also promote wider considerations, including ethical and moral decision making11. Complexity in care episodes and an appreciation of multidisciplinary contributions to optimisation of clinical outcomes and care experiences are also valued.

Learners and educators

A clinical conversation in a digital space is not the same as online learning in the traditional sense. Learners have varied experience of using digital learning platforms, and it is not uncommon for them to present to the digital clinical placement with unrealistic expectations of the information they will gain and how they will achieve it. It is not unusual, from The Christie Hospital education teams’ observations, that learners expected to learn through one-way information-giving and were then somewhat bemused when the digital placement required collaborative dialogue, a shared responsibility for knowledge to be generated and for new knowledge and applications of the knowledge to emerge.

The Christie radiotherapy educators anticipated significant challenges when proposing a shift to a blended digital and physical clinical placement model. In discussions with various stakeholders, key concerns included: the digital placement would be sub-optimal compared with a physical placement; learners would not necessarily engage; there would be less opportunity for feedback and assessment; it was unclear how the learning would demonstrate contributions to their academic award.

Drawing on tacit and experiential knowledge – born from vast shared experience of supporting learners and practitioners in both the digital and physical clinical setting – the team drew on a range of knowledge, skills and capabilities that would address the concerns raised. This included the implementation of a coaching framework to support programme contracting, mutual agreements and expectations of the learning environment. Learners were required to reflect daily and to provide anonymised feedback on peers they were learning and working with. This enabled a safe and private learning space, which was regulated virtually through learner and peer feedback. Furthermore, learners were tasked to consider what they were learning (process) and how they were socialising (people), which provided an opportunity to explore team reflexivity to encourage self and team regulation.

The blended clinical placement framework (either digital only or combined with a physical site placement) produced high-quality clinical placement reports rooted in individualised consideration for a learner’s personal journey of growth in professional capabilities. While purposefully creating a shift in traditional measures of pre-registration performance, the reports generated were relevant to professional growth and supported by coaching conversations encouraging learners to follow their own interest, identify opportunities for development and commit to positive change. Consistently, learners were guided by conversations with patient line of sight at its core.

The design and implementation of a digital (alone) and blended (digital and physical) clinical placement model has unequivocally demonstrated that learners do benefit from this model.

Initial data collected by academic colleagues based at St George’s, University of London, demonstrated significant learning growth across eight professional capabilities, across two cohorts of learners. Each cohort demonstrated similar trends. This growth (learning gain) will be explored in a forthcoming article.

Summary of key learning points

This article commenced with the notion that practice placement learning environments are complex and multifaceted. A digital element to the clinical educational offering creates a further dimension in complexity and should not be adopted without a clear and systematic appreciation of all elements of the placement experience that may enhance, or indeed add, risk. A shift to a digital space does not constitute a quick win to increase clinical placement capacity and we must employ caution as a professional community to maintain and enhance clinical placement provision that meet the needs of our key stakeholder, our patients.

A key advantage of a digital clinical placement is its scalability. Not bound by geographic borders, it is widely accessible using the digital resources on offer on the NHS Digital Tenancy. In terms of maximisation of capacity to access the programme, the team would advise caution.

The key limiting factor to substantial growth is the visibility of the learner. In a 12-month period, this placement has successfully moved from 70 to 400 clinical placements. Further work is under way to establish the educationalist-to-learner ratio to realise a positive and meaningful placement experience, and the radiotherapy education team at The Christie NHS Foundation Trust looks forward to continuing to share its experiences.

Alison Sanneh is a Therapeutic Radiographer and Principal Radiotherapy Educator at The Christie NHS Foundation Trust.

Wesley Doherty is a Therapeutic Radiographer and Radiotherapy Clinical Educator at The Christie NHS Foundation Trust.

Acknowledgments: Proton Beam Services and Digital Services, The Christie Hospital NHS Trust; Health Education England; the CPEP Project Team; Julie Hendry and Lauren Fantham at St George’s, University of London.

References

1. NHS. Cancer Workforce Plan. 2017.

2. Health Education England. Reducing Pre-registration Attrition and Improving Retention Report. 2018.

3. Health Education England. Clinical Placements Expansion Programme (AHPs). 2020.

4. Health Education England. NHS Education Contract. 2020. Available at www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/NHS%20Education%20Contract%20-%20April%202021-March%202024.pdf Accessed 28 January 2022.

5. Health Education England. HEE Quality Framework. 2021. Available at https://nshcs.hee.nhs.uk/publications/health-education-england-hee-quality-framework-from-2021/

6. Smith ML, Erwin J and Diaferio S. Role and Responsibility Charting (RACI). Project Management Forum (PMForum), 2005. 5.

7. Coleman L. Education and Career Framework for the Radiography Workforce. 2013. The Society and College of Radiographers, London, UK.

8. Health and Care Professions Council. Standards of Proficiency: Radiographers. 2013: HCPC.

9. NHS. The NHS Long Term Plan. 2019.

10. Ireland J and Mouthaan M. Perspectives on curriculum design: comparing the spiral and the network models. Research Matters, 2020.

11. Liao H-C and Wang Y-H. Storytelling in medical education: narrative medicine as a resource for interdisciplinary collaboration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2020. 17(4): p1135.