Embedding a research culture in clinical radiography

Improving the care, experience and health outcomes of our patients is central to our involvement in research

Research has often been perceived to be undertaken by academics in universities and medics in the clinical field. While this is true to a certain extent, and research is often led or supported by those with research training and familiarity, realistically no research is ever carried out by one individual and the research team will comprise many people who bring different knowledge, skills and experience to the table.

Excitingly, a dynamic change is being seen among radiography students and those working in the diagnostic and therapeutic radiography disciplines, where there is a desire to engage with research to provide or implement the evidence that underpins practice. This may be part of undergraduate training or additional postgraduate education, as an adjunct to clinical or operational duties as part of personal and professional career development, or as a pillar of the main role. Regardless of the setting or hierarchy, improving the care, experience and health outcomes of our patients is always central to our involvement in research. Although the challenges to radiographers participating in or contributing to evidence-based practice are well documented1-3, investment in staff and the provision of support to enable them to take part in the many forms of research should be encouraged.

To coincide with the launch of the new College of Radiographers Research Strategy (2021-2026)4 the authors wanted to highlight the importance of research and to provide some practical ideas for those wishing to begin or progress their proficiency. Both authors have worked in clinical research roles, leading their own projects and supporting teams to undertake research. Both have personal ambitions to embed research into radiography practice and make it an accepted part of everyone’s role.

The value of research in radiography

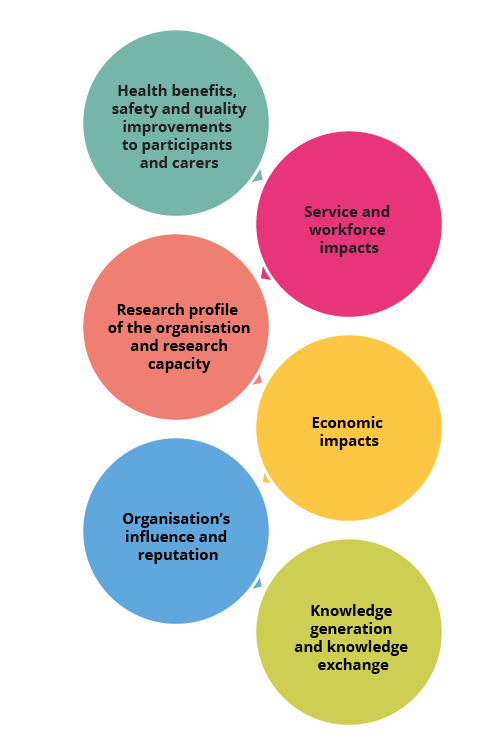

There is shared agreement that research benefits service users, the organisation in which research takes place and the staff engaging with research5. However, there are wider benefits to research that may not immediately be apparent. The VICTOR tool6 helps to identify the visible impacts of research within an organisation and can be useful for demonstrating to executives and managers the value of embedding research as “core business”7. The six key domains are demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The tangible impacts of research6

As well as the health impacts, health literacy gains, safety improvements and social capital that research facilitates for patients and their carers, there are multiple organisational achievements. These include service changes, the development of new clinical or transferable skills, changes to job roles or structures, and collective action by teams that can be born out of research. Importantly, research itself can increase staff confidence in skills, provide a mechanism for patient and public involvement, prompt new career choices, build clinical and research partnerships and foster future collaborative projects (grant funded or locally initiated). Of particular importance during times of austerity are the cost-effectiveness changes, commercialisation and income generation that research can carry as well as professional cohesion, research reputation and recruitment and retention of staff. The latter are not typically the early outcomes of research activity and these successes develop over time.

Radiography departments can be involved in research in two major ways. They can support clinical research trials developed by others as a participating site, or they can initiate primary research. Across diagnostic and therapeutic radiography, supporting research trials offers patients the opportunity to be involved in research and drives the advancement of services and treatments that have been tested thoroughly and shown to bring direct benefits to patients. Multiple recent impact cases can be celebrated. For example, at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, findings from the CHHiP and Fast Forward trials supported departments to adopt reduced fractionation regimes, which subsequently enabled them to continue with service delivery despite clinical and environmental pressures8,9. In diagnostic radiography, the feasibility of offering early access to cross-sectional imaging for suspected scaphoid injuries was tested and resulted in fewer patient visits, reduced emergency doctor hours, it avoided treatment costs associated with wrist immobilisation and saved MRI scans during the pandemic10.

"Great oaks from little acorns grow"

As highlighted earlier, radiography professionals can be involved in research in a variety of ways. Over the past decade, there have been calls to cultivate training for professionals who wish to combine research with clinical roles, as well as clear research career pathways relevant to the practice levels within the profession11. Recently, there is anecdotal evidence of an increase in advertised NHS research posts in radiography, in addition to emerging educational programmes and guidance for those pursuing research-focused clinical academic careers11,12.

Fundamentally, all staff will help to deliver research when they provide care (diagnostic or therapeutic) for a patient who is voluntarily participating in a research trial. However, there are also those who will extend their involvement to recruitment, being a feasibility adviser, co-applicant or principal investigator and chief researcher. For those in research radiographer positions, there will be similarities and differences in roles and responsibilities between disciplines. Like the clinical research nurse structure, therapeutic research radiographers and sonographers may tend to work within a specialty or disease site, for example, breast, colorectal and prostate, with radiographers developing the processes and treatment plans for patients within a portfolio of relevant studies. In contrast, diagnostic research radiographers will be actively involved in the image acquisition for a range of clinical research studies with little involvement in an individual’s ongoing care pathway or multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. Similarities include input into the practical aspects of study set-up, development of protocols, data entry and database management, ongoing project oversight, contributing to research dissemination, working within the wider MDT and taking a lead role in research and development for the department.

A national strategy

for radiography research

Radiography sits within a wider collection of 14 allied health professions (AHPs), which are considered central to developing, delivering and assessing the impact of research that demonstrates the quality, safety and efficiency of services required to achieve change13. The link between research evidence and best practice informs their decision-making processes, underpinned by patient-centred care and recognition of the value of a multidisciplinary approach. Although the radiography profession lags behind nursing and some other AHPs in terms of frameworks for research capacity development, the College of Radiographers’ publication of a research strategy for its members since 2016 is helping to maximise opportunities and increase the visibility of radiography research14.

Building a research

culture in radiography

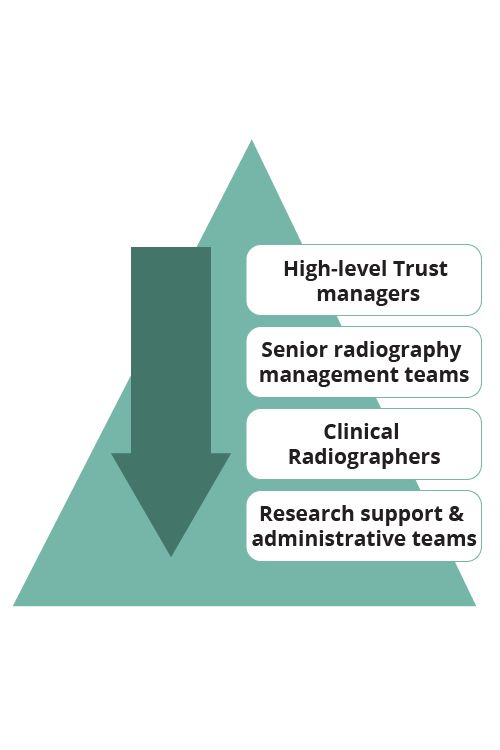

The College of Radiographers’ Research Strategy4 aims to “embed and enable research at all levels of radiography practice and education”. It is important that, as professionals, we implement the strategy, understand how we can use it in our own departments and work collaboratively across clinical and academic institutions to generate and transfer knowledge. A vision for research cannot be a superficial paper or a “tick box” exercise, it must be embedded and supported at every hierarchical level of an organisation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Radiographic managerial structure

High-level management, service-level delivery managers and radiographers all play an essential role in ensuring research becomes the norm and not just an added extra. High-level managers are essential to supporting the vision – embedding it into trust strategy and advocating its importance demonstrates commitment and governs engagement. Service-level managers are responsible for embedding the vision into local services and conveying the vision through their operations. It is essential that managers create environments and systems for nurturing research cultures by ensuring that staff feel valued, respected and engaged. Equally important is the role of service-level managers in embedding a culture of research by providing time, resources and opportunity for their teams to engage. They have a key role in ensuring support for continued professional development and engagement with research activities by signposting to opportunities for research training or involvement, by advocating dedicated research roles within workforce planning, and by making research a regular discussion during individuals’ professional development reviews. Similarly, it is important for radiographers to take up those opportunities, become role models to their peers and help support the next generation of researchers through the process of mentorship.

Together, there is the opportunity to develop a joint departmental research strategy built on appreciation of our shared values and a collective approach to the implementation of evidence-based practice rather than a “top-down” approach from research leads. A research strategy enables practitioners to focus on their strengths and provides clear direction on the range of research activities to be undertaken as well as the development of staff to achieve aspirations. It can inform wider strategy and policy development, resource allocation and the setting of targets (also commonly known as key performance indicators). There are multiple ways to develop a local radiography research strategy but the most successful are those that are realistic, progressive and developed in partnership by all key stakeholders.

In the current climate, embedding evidence-based practice and creating a research culture may require innovative thinking and novel strategies to overcome common barriers to undertaking research related to time constraints, staff confidence and local priorities, based on competing demands on service. For those with a desire to encourage staff to become research engaged or active, success relies on raising staff awareness of research, building relationships that support research activity (both within the organisation and externally with academic or industry partners) and developing the local infrastructure required to ensure sustainability. These are likely to be associated with financial or time implications as well as workforce changes, but they are small penalties to pay compared with the benefits afforded by delivering good research.

Getting started

There are multiple ways to get started and several useful resources to help you (see the references at the end of this article). First and foremost, do not be afraid to put yourself out there: remember, everyone must start somewhere. Where possible, volunteer to be part of an existing project (collect some data, do some analysis, etc). If necessary, look outside of radiography because there may be a broader group of AHP active researchers in your organisation with research interests that align with yours. This will not only provide you with experience but will illustrate your interest to others, who may be able to bring you on to another project and allow you to identify your training needs in line with established research frameworks5.

Developing your networks is key. Try to join and get involved with local and national groups – these might be internal at your trust or external online forums. On social media, follow research individuals and organisations that often share information and openings for team members on forthcoming projects and funding opportunities. Set up a local journal or breakfast club – there will be many like-minded radiographers in your department who share your interest but also do not know where to start. This will not only help to establish your local network but will develop your critical appraisal skills – it may even help you to identify areas relevant to your own practice where research could be undertaken to improve clinical delivery and patient care.

Similarly, get involved in online journal clubs, for example @MedRadJclub, and join your local Council for Allied Health Professions Research hub, where you will have access to shared resources, see the work others (including other AHP groups) are undertaking and, again, build those all-important networks. Looking closer to home, the Getting into Research guide from the Society and College of Radiographers provides an essential overview of radiography research, including details of roles, key terminology, and patient and public involvement and engagement15. Furthermore, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the National Cancer Research Institute have an abundance of online resources and, if you are interested in something more formal, the NIHR Fellowship Programme can provide support from pre- to post-doctoral stages16.

Summary

When we consider local research activity, management and strategy, there is diversity not only across the two radiographic disciplines but also across individuals, teams and departments within both professions. The approaches adopted to deliver and embed research may not be identical, but what is important is that these different levels of implementation and processes exist across education and practice. The College’s strategy is not prescriptive or intended to fit all, it is designed to be a guide to help underpin the approach each department (or individual) takes. What is important is the understanding and acceptance that research is every radiographer’s business. The proverb “great oaks from little acorns grow” is so relevant to research. Through investment in radiographer research skills training and further development of networks, collaboration and mentorship we can embed a culture of research, build research capacity and enhance the future services and care received by our patients.

Martine Harries is a Research and Senior CT Radiographer at the Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust.

Amy Taylor is a Senior Lecturer in Medical Imaging at the University of Exeter and a Therapeutic Radiographer.

References

1. Probst H, Harris R, McNair H, Baker A, Miles E and Beardmore C. Research from therapeutic radiographers: an audit of research capacity within the UK. Radiography, 2015; 21:112e8.112-118. Available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2014.10.009

2. Taylor A and Shuttleworth P. Supporting the development of the research and clinical trials therapeutic radiographers’ workforce: The RaCTTR survey. Radiography, 2021; 27(1). S20-S27. Available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2021.07.025

3. Nightingale J. Establishing a radiography research culture – are we making progress? Radiography, 2016; 22(4), 265-266. Available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2016.09.002\

4. The College of Radiographers. Research Strategy 2021-2026. Available at CoR Research Strategy 2021 - 26 | CoR (collegeofradiographers.ac.uk)

5. Council for Allied Health Professions Research. Shaping Better Practice Through Research: A Practitioner Framework. 2019. Available at Shaping Better Practice Through Research: A Practitioner Framework (csp.org.uk)

6. Holliday J, Jones N and Cooke J, funded by National Institute of Health Research. Welcome to VICTOR. A Pack for Coordinators Wishing to Use the VICTOR Approach. Available at https://hseresearch.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/VICTOR-pack.pdf.

7. Gee M and Cooke J. How do NHS organisations plan research capacity development? Strategies, strengths and opportunities for improvement. BMC Health Services Research, 2018; 18(1),198. Available at DOI:10.1186/s12913-018-2992-2

8. Dearnaley D, Syndikus I, Mossop H, Khoo V, Birtle A, Bloomfield D et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: five-year outcomes of the randomised, noninferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. The Lancet 2016;17(8).1047-1060. Available at DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30102-4

9. Brunt AM, Haviland JS, Wheatley DA, Sydenham MA, Alhasso A, Bloomfield DJ et al. Hypofractionated breast radiotherapy for one week versus three weeks (FAST-Forward): five-year efficacy and late normal tissue effects results from a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2020; 395(10237): 1613-1626. Available athttps://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30932-6

10. Snaith B, Harris M, Hughes J, Spencer N, Shinkins B, Tachibana A, Bessant G and Robertshaw S. Evaluating the potential for cone beam CT to improve the suspected scaphoid fracture pathway: InSPECTED – a single-centre feasibility study. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences 2021. Available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmir.2021.10.002

11. The Health Education England (HEE) and National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Clinical Academic Programme. Available at www.nihr.ac.uk/explore-nihr/academy-programmes/hee-nihr-integrated-clinical-academic-programme.htm

12. The Society of Radiographers. Clinical Academic Radiographer: Guidance for the Support of New and Established Roles. Available at https://www.sor.org/learning-advice/professional-body-guidance-and-publications/documents-and-publications/policy-guidance-document-library/clinical-academic-radiographer-guidance-for-the-su

13. NHS England. Allied Health Professions into Action. Using Allied Health Professionals to Transform Health, Care and Wellbeing 2016/17 to 2020/21. 2017. Available at ahp-action-transform-hlth.pdf (england.nhs.uk)

14. Strudwick R, Harris M, McAlinney H, Plant P, Shuttleworth P, Woodley J, Harris R and O’Regan T. The College of Radiographers Research Strategy for the next five years. Radiography, 2021; 27(1): S5-S8. Available at DOI:10.1016/j.radi.2021.06.010

15. The Society and College of Radiographers. Getting into Research: A Guide for Members of the Society of Radiographers, 2nd edn (London: SCoR, 2019). Available at Getting into Research: A Guide for Members of the Society of Radiographers | SoR

16. National Institute of Health Research. NIHR Fellowship Programme. Available at www.nihr.ac.uk/explore-nihr/academy-programmes/fellowship-programme.htm