Compassionate leadership

Leading with compassion fosters happier and better-motivated staff, who are well equipped to offer high-quality patient care

Leadership has become a highly used term in healthcare but the meaning itself is very much down to individual interpretation. In our everyday lives and upbringings, we will all have experienced leadership in many forms but if it is not in keeping with the definition of leadership in our minds, it may not be recognised as such.

So, with that in mind, what does leadership even mean?

Leadership as a concept is very much centred on individuals influencing, guiding and motivating others to accomplish an objective in an organisational setting. The focus when leadership is a concept is often on achieving the end goal – and “how” this is achieved often is not as important as “if” this is achieved. Leadership becomes very task orientated, often hierarchical in nature and command and control behaviours become the everyday norm, rather than being reserved for crisis situations. As much as this may “get the task done”, the impact of these behaviours on individuals can be demoralising, demotivating and detrimental to health and wellbeing and, when this occurs in a healthcare setting, the impact on patient care can be devastating. Many reports published over the past decade demonstrate this1-3.

The publication of these reports provided the evidence and urgency to address the leadership failings across our health and care systems. A call to action was made from the government to all organisations in the NHS to ensure they were dedicated to putting the patient at the centre of care, with compassion being a core value and behaviour. This led to multiple reviews, research and surveys on what we understood healthcare leadership to mean, to feel and to experience.

A large multi-method study4, which examined the culture and behaviour in the English NHS, found several examples of great culture and care but also several inconsistencies. The review demonstrated the importance of leadership for setting mission, direction and tone of organisational goals. In organisations with high-quality management, they created positive, innovative and caring cultures from the board to frontline delivery of care. In combination, when senior teams and individuals were empowered and encouraged to address challenges and given accountability, they thrived in this culture to work alongside management to achieve unifying goals. Of course, in organisations that did not share these cultures, staff were left feeling disempowered and struggled to deliver care effectively.

Do we know what type of leadership is important?

This is a question often asked by people wanting to become “better leaders”. Modern-day leadership has very much moved away from a rigid definition to more of a collective agreement of inclusive values and compassionate behaviours, creating cultures that empower, inspire and motivate. In the context of healthcare, this is important for all who work in or use healthcare services and includes patients, peers and professionals.

The work of Professor Michael West and others has led to a new approach for healthcare leadership, based on the core value of compassion. In his book5, Professor West describes those who demonstrate compassionate leadership as having a focus on relationships through careful listening to, understanding, empathising with and supporting other people. This enables those they lead to feel valued, respected and cared for, so they can reach their potential and do their best work. He also references the clear evidence that compassionate leadership results in more engaged and motivated staff with high levels of wellbeing, which, in turn, results in high-quality patient care and, of course, that has never been more important than now.

It seems such a simple concept to lead with compassion because, generally speaking, people seek out careers in healthcare because they want to care for and support others. However, there are many barriers to enabling people to lead with the compassion they aspire to. These include poor leadership from those in senior positions or positions of power; lack of role models who showcase compassionate leadership; poor working conditions; excessive workload; perceived lack of time6 and, in the words of Professor West himself: “Compassionate leadership is not a soft option, it requires huge courage, resilience, and belief, and sustaining cultures of high-quality compassionate care requires compassionate leadership at every level – local, regional and national – and in interactions between all parts of the system – from local teams to national leaders.”5

How can we lead with compassion?

First, it is important to understand what people need from healthcare leaders. The global pandemic, years of underfunding, demand exceeding capacity and systemic discrimination have all put incredible and unprecedented pressures on healthcare systems. We see the impact of this on ourselves, on those around us and on the quality of care we can provide.

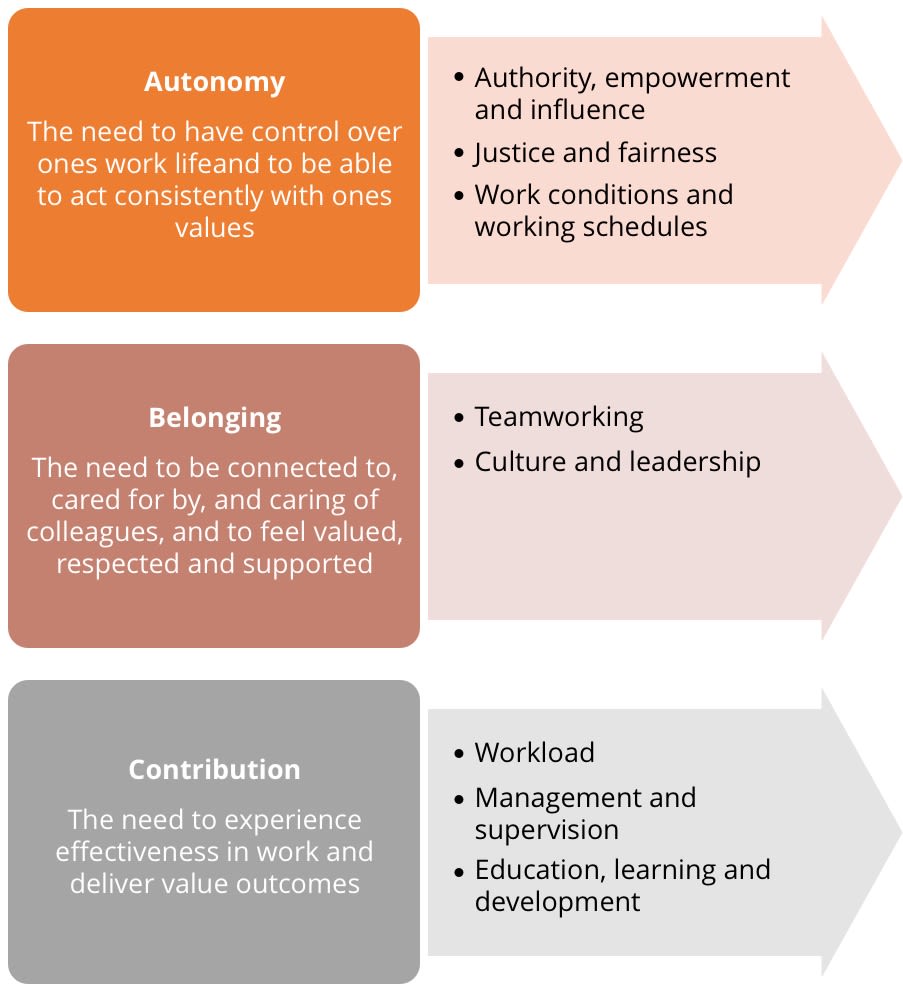

A report7 commissioned by the Royal College of Nursing Foundation during the pandemic looked to investigate the impact of excessive demands on nurses and midwives, who were already at risk of stress and burnout. The research team had also been asked to identify strategies to ensure wellbeing and motivation at work, and to minimise workplace stress. The research evidence suggested that people have three core needs that must all be met in order to flourish and thrive at work. These included:

• Autonomy – the need to have control over their work lives and to be able to act consistently with their values.

• Belonging – the need to be connected to, cared for by and caring of others around them at work, and to feel valued, respected and supported.

• Contribution – the need to experience effectiveness in what they do and deliver valued outcomes.

The review identified key areas where action is needed within each of the core needs (see Figure 1). This review was specifically designed for nurses and midwives but there is huge value in applying this to other healthcare professional groups.

Figure 1. Action on the core needs. Adapted from West, Bailey and Williams (2020)

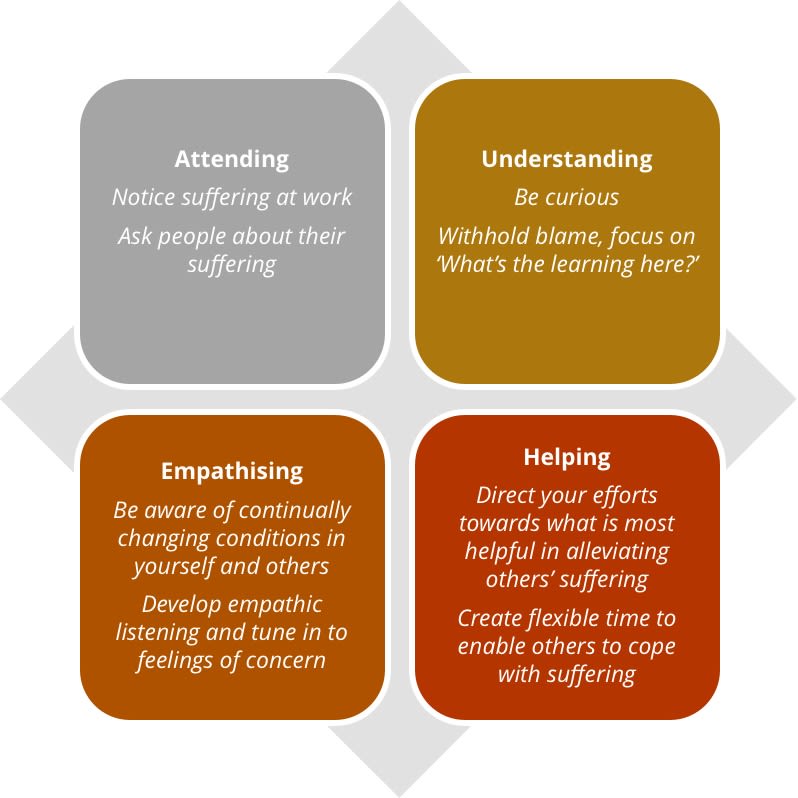

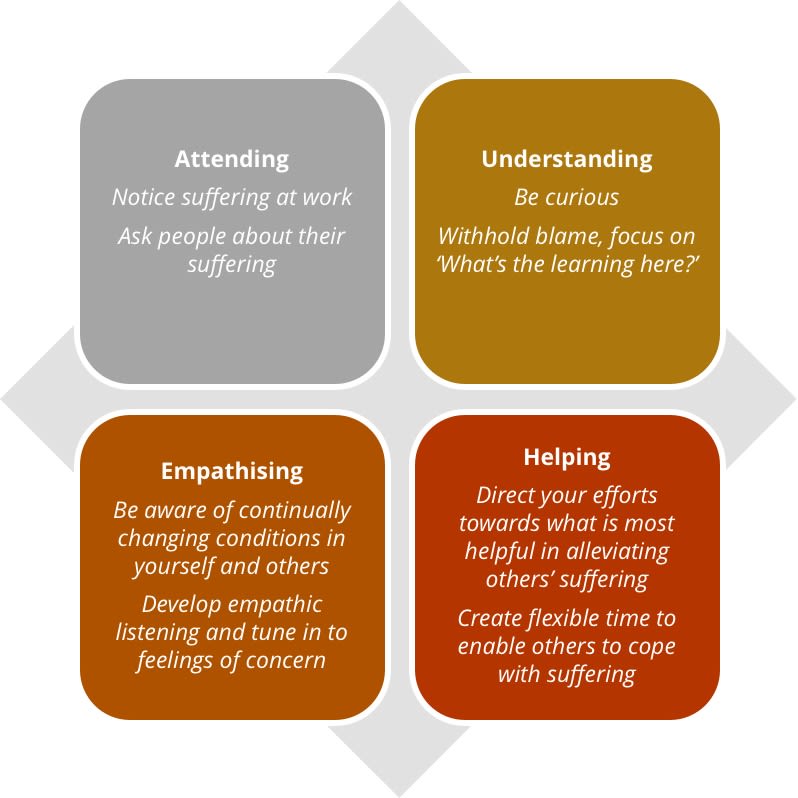

And when we know what people need, the focus for leaders is on how this can be achieved. The four behaviours of compassionate leadership have been described beautifully by Bailey and West (2022)8 based on the work of Atkins and Parker (2012)9. They describe deep behaviours that should become part of your daily work practice, regardless of your level of seniority or your professional role (see Figure 2). They suggest you can practise compassion through how you attend, understand, empathise and help others you work alongside.

Figure 2. The four behaviours of compassionate leadership. Adapted from Bailey and West (2022), and Atkins and Parker (2012)

What about inclusive leadership?

As well as creating cultures where people can thrive, it is equally important that people feel like they belong. A system that attributes blame when things go wrong, rather than trying to understand the deep-rooted factors that contribute when things do not go as we expect, creates fear and anxiety. This is particularly harmful for people who also face disproportionate bullying, harassment and systemic discrimination, such as Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic colleagues10, staff with disabilities11 and those from sexual orientation or gender identity minority groups12. This is further evidenced in our national NHS Staff Surveys, Workforce Race Equality Standard report and Workforce Disability Equality Standard report.

Inclusive leaders create psychologically safe spaces13 for people to openly speak about their personal experiences of discrimination, knowing they will be believed and that, in return for sharing their trauma, meaningful action will take place through organisational policies and procedures that are not just tick-box exercises. They create mechanisms where every voice is heard, especially those voices that are often oppressed for fear of the repercussions of stereotyping and profiling against their race, ethnicity, culture, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or disability. Often this means speaking truth to power, which requires courage and commitment, taking accountability and a drive for constant improvement and continuous learning.

Compassionate inclusive leaders really care about their teams, recognising and celebrating difference and valuing diversity, calling out racism, ableism, and discrimination of all forms and taking meaningful action. They create psychologically safe cultures where people can thrive, not being fearful of perceived failure with honesty, vulnerability and empathy being key values that all team members share.

For those interested in learning more, visit the Nurturing Compassionate and Inclusive NHS Cultures course and NHSi Civility and Respect Toolkit pages for more information.

What’s out there to help support leadership learning?

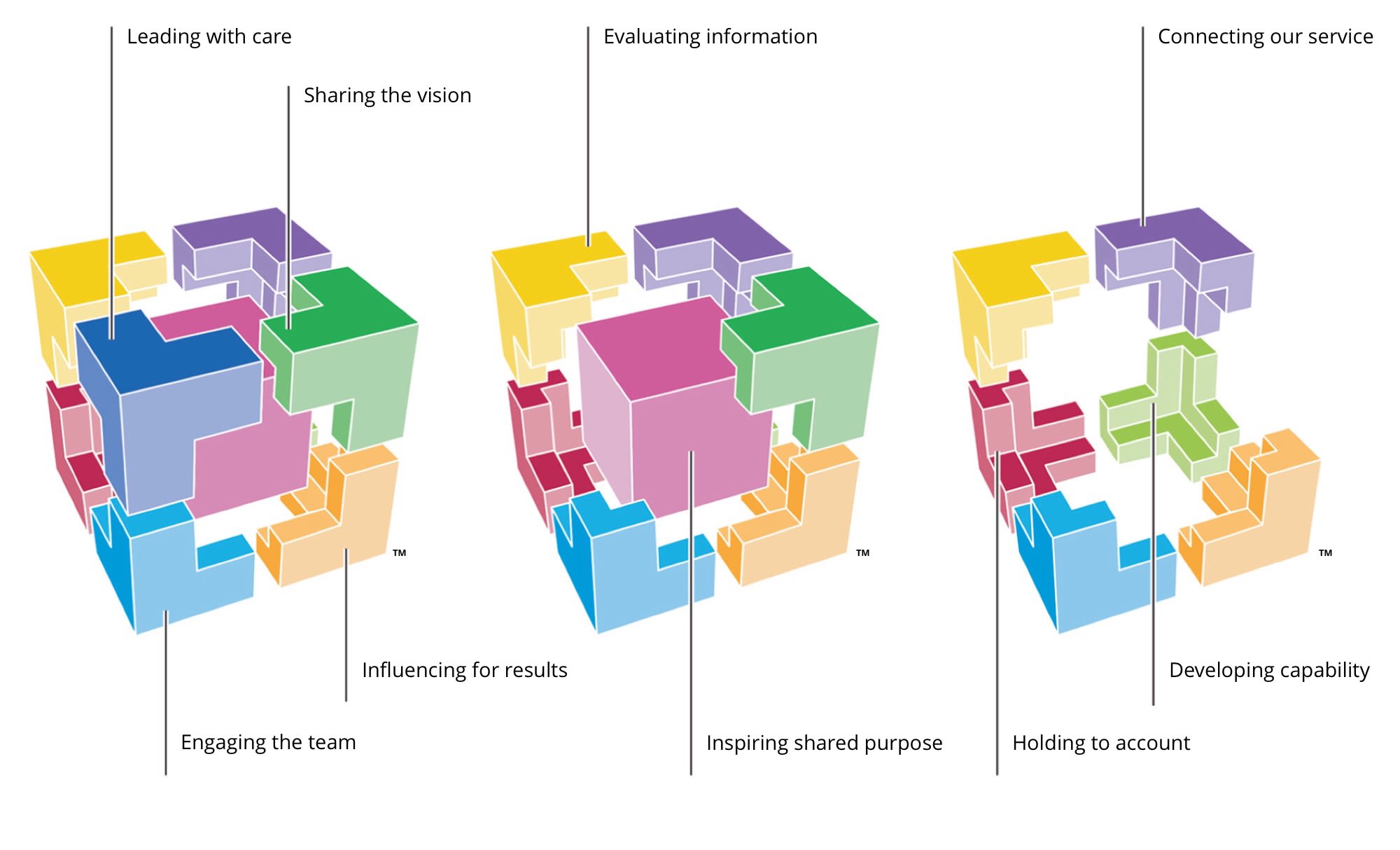

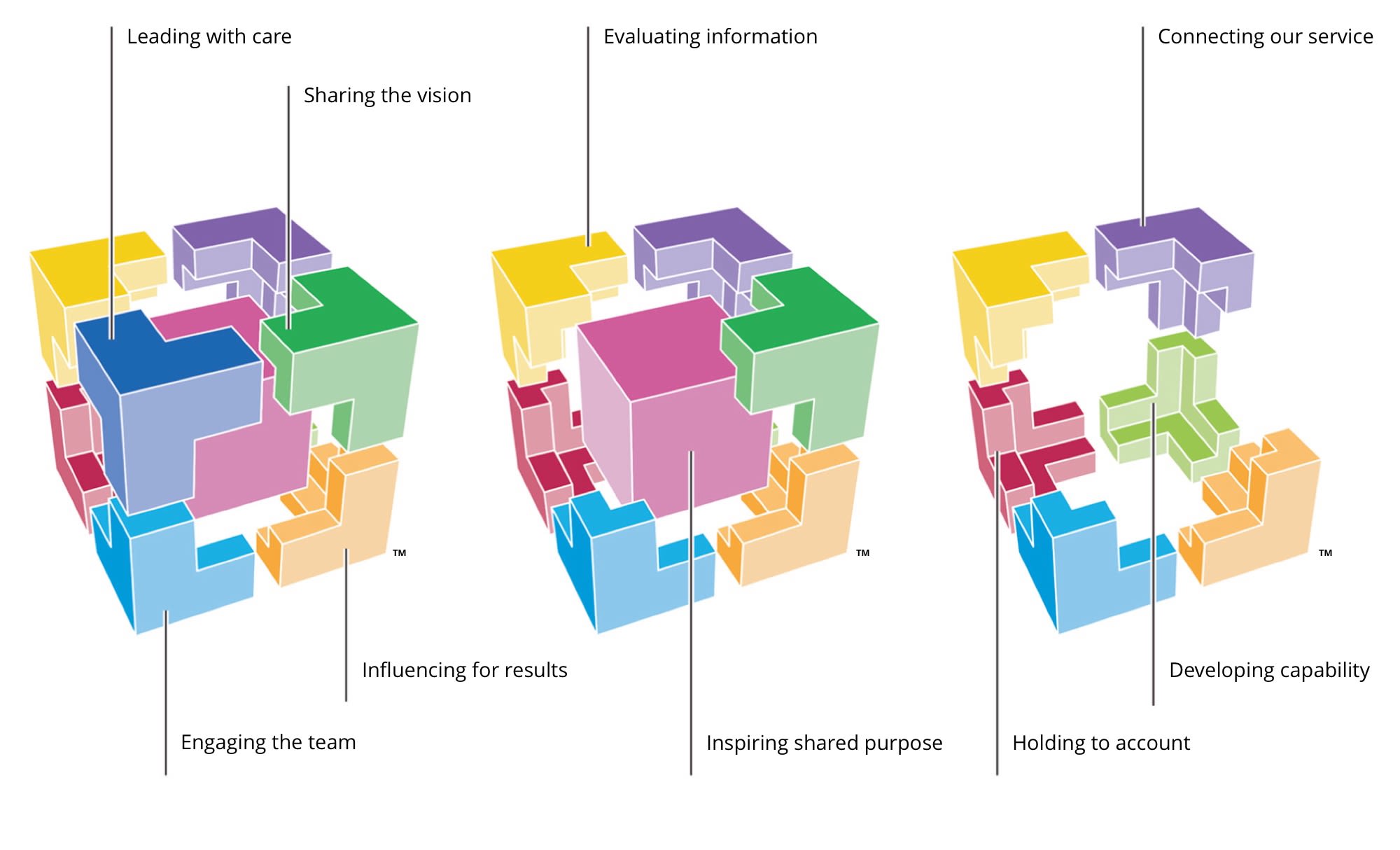

Since its inception, the NHS Leadership Academy has aspired to develop leaders at all levels from across health and care to have a positive effect on staff engagement and, in turn, improve patient outcomes. It co-designed the Healthcare Leadership Model (HLM) to help support healthcare workers of all backgrounds to become better leaders. It aims to help you understand how your leadership behaviours affect the culture and climate you, your colleagues and teams work in.

The HLM is made up of nine “leadership dimensions”. For each dimension, leadership behaviours are shown on a four-part scale, which ranges from “essential” through “proficient” and “strong” to “exemplary”. Within these scales, the leadership behaviours themselves are presented as a series of questions to encourage reflection (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The NHS Healthcare Leadership Model

In support is the HLM app, designed to build a repository of leadership practice in action to help understand at a deeper level what great leadership behaviour looks and feels like. It is intended to influence the user to notice positive examples of leadership in action so the action is easy to practise again in future.

For some, formal training is helpful to support their leadership learning journey. The NHS Leadership Academy is well known for its flagship programmes, designed to support healthcare workers from the start of their careers all the way to board positions. The Edward Jenner Programme is the first port of call if you are looking to build a strong foundation of leadership skills that can help enhance your confidence and competence in your role. The programme has been designed to offer flexibility – the modules are free to access and based online.

In addition to formal learning, there are several other leadership learning resources that are free to access online:

• Bitesize Learning offers short guides, developed by experts, that are an hour or less in length. Topics include courageous conversations, creating time to share ideas and team working.

• The Inspiration Library contains podcasts, videos and blogs on a wide range of topics.

• #ProjectM is a place and space for team leaders and managers to connect, share and learn together. ProjectM is free to access and many of its conversations are facilitated over social media.

• Executive Suite is a range of opportunities for senior leaders to access support and development for themselves and to help them support the development of their staff into the future.

Leadership has become a highly used term in healthcare but the meaning itself is very much down to individual interpretation. In our everyday lives and upbringings, we will all have experienced leadership in many forms but if it is not in keeping with the definition of leadership in our minds, it may not be recognised as such.

So, with that in mind, what does leadership even mean?

Leadership as a concept is very much centred on individuals influencing, guiding and motivating others to accomplish an objective in an organisational setting. The focus when leadership is a concept is often on achieving the end goal – and “how” this is achieved often is not as important as “if” this is achieved. Leadership becomes very task orientated, often hierarchical in nature and command and control behaviours become the everyday norm, rather than being reserved for crisis situations. As much as this may “get the task done”, the impact of these behaviours on individuals can be demoralising, demotivating and detrimental to health and wellbeing and, when this occurs in a healthcare setting, the impact on patient care can be devastating. Many reports published over the past decade demonstrate this1-3.

The publication of these reports provided the evidence and urgency to address the leadership failings across our health and care systems. A call to action was made from the government to all organisations in the NHS to ensure they were dedicated to putting the patient at the centre of care, with compassion being a core value and behaviour. This led to multiple reviews, research and surveys on what we understood healthcare leadership to mean, to feel and to experience.

A large multi-method study4, which examined the culture and behaviour in the English NHS, found several examples of great culture and care but also several inconsistencies. The review demonstrated the importance of leadership for setting mission, direction and tone of organisational goals. In organisations with high-quality management, they created positive, innovative and caring cultures from the board to frontline delivery of care. In combination, when senior teams and individuals were empowered and encouraged to address challenges and given accountability, they thrived in this culture to work alongside management to achieve unifying goals. Of course, in organisations that did not share these cultures, staff were left feeling disempowered and struggled to deliver care effectively.

Do we know what type of leadership is important?

This is a question often asked by people wanting to become “better leaders”. Modern-day leadership has very much moved away from a rigid definition to more of a collective agreement of inclusive values and compassionate behaviours, creating cultures that empower, inspire and motivate. In the context of healthcare, this is important for all who work in or use healthcare services and includes patients, peers and professionals.

The work of Professor Michael West and others has led to a new approach for healthcare leadership, based on the core value of compassion. In his book5, Professor West describes those who demonstrate compassionate leadership as having a focus on relationships through careful listening to, understanding, empathising with and supporting other people. This enables those they lead to feel valued, respected and cared for, so they can reach their potential and do their best work. He also references the clear evidence that compassionate leadership results in more engaged and motivated staff with high levels of wellbeing, which, in turn, results in high-quality patient care and, of course, that has never been more important than now.

It seems such a simple concept to lead with compassion because, generally speaking, people seek out careers in healthcare because they want to care and support others. However, there are many barriers to enabling people to lead with the compassion they aspire to. These include poor leadership from those in senior positions or positions of power; lack of role models who showcase compassionate leadership; poor working conditions; excessive workload; perceived lack of time6 and, in the words of Professor West himself: “Compassionate leadership is not a soft option, it requires huge courage, resilience, and belief, and sustaining cultures of high-quality compassionate care requires compassionate leadership at every level – local, regional and national – and in interactions between all parts of the system – from local teams to national leaders.”5

How can we lead with compassion?

First, it is important to understand what people need from healthcare leaders. The global pandemic, years of underfunding, demand exceeding capacity and systemic discrimination have all put incredible and unprecedented pressures on healthcare systems. We see the impact of this on ourselves, on those around us and on the quality of care we can provide.

A report7 commissioned by the Royal College of Nursing Foundation during the pandemic looked to investigate the impact of excessive demands on nurses and midwives, who were already at risk of stress and burnout. The research team had also been asked to identify strategies to ensure wellbeing and motivation at work, and to minimise workplace stress. The research evidence suggested that people have three core needs that must all be met in order to flourish and thrive at work. These included:

• Autonomy – the need to have control over their work lives and to be able to act consistently with their values.

• Belonging – the need to be connected to, cared for by and caring of others around them at work, and to feel valued, respected and supported.

• Contribution – the need to experience effectiveness in what they do and deliver valued outcomes.

The review identified key areas where action is needed within each of the core needs (see Figure 1). This review was specifically designed for nurses and midwives but there is huge value in applying this to other healthcare professional groups.

Figure 1. Action on the core needs. Adapted from West, Bailey and Williams (2020)

And when we know what people need, the focus for leaders is on how this can be achieved. The four behaviours of compassionate leadership have been described beautifully by Bailey and West (2022)8 based on the work of Atkins and Parker (2012)9. They describe deep behaviours that should become part of your daily work practice, regardless of your level of seniority or your professional role. They suggest you can practise compassion through how you attend, understand, empathise and help others you work alongside.

Figure 2. The four behaviours of compassionate leadership. Adapted from Bailey and West (2022), and Atkins and Parker (2012)

What about inclusive leadership?

As well as creating cultures where people can thrive, it is equally important that people feel like they belong. A system that attributes blame when things go wrong, rather than trying to understand the deep-rooted factors that contribute when things do not go as we expect, creates fear and anxiety. This is particularly harmful for people who also face disproportionate bullying, harassment and systemic discrimination, such as Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic colleagues10, staff with disabilities11 and those from sexual orientation or gender identity minority groups12. This is further evidenced in our national NHS Staff Surveys, Workforce Race Equality Standard report and Workforce Disability Equality Standard report.

Inclusive leaders create psychologically safe spaces13 for people to openly speak about their personal experiences of discrimination, knowing they will be believed and that, in return for sharing their trauma, meaningful action will take place through organisational policies and procedures that are not just tick-box exercises. They create mechanisms where every voice is heard, especially those voices that are often oppressed for fear of the repercussions of stereotyping and profiling against their race, ethnicity, culture, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or disability. Often this means speaking truth to power, which requires courage and commitment, taking accountability and a drive for constant improvement and continuous learning.

Compassionate inclusive leaders really care about their teams, recognising and celebrating difference and valuing diversity, calling out racism, ableism, and discrimination of all forms and taking meaningful action. They create psychologically safe cultures where people can thrive, not being fearful of perceived failure with honesty, vulnerability and empathy being key values that all team members share.

For those interested in learning more, visit the Nurturing Compassionate and Inclusive NHS Cultures course and NHSi Civility and Respect Toolkit pages for more information.

What’s out there to help support leadership learning?

Since its inception, the NHS Leadership Academy has aspired to develop leaders at all levels from across health and care to have a positive effect on staff engagement and, in turn, improve patient outcomes. It co-designed the Healthcare Leadership Model (HLM) to help support healthcare workers of all backgrounds to become better leaders. It aims to help you understand how your leadership behaviours affect the culture and climate you, your colleagues and teams work in.

The HLM is made up of nine “leadership dimensions”. For each dimension, leadership behaviours are shown on a four-part scale, which ranges from “essential” through “proficient” and “strong” to “exemplary”. Within these scales, the leadership behaviours themselves are presented as a series of questions to encourage reflection (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The NHS Healthcare Leadership Model

In support is the HLM app, designed to build a repository of leadership practice in action to help understand at a deeper level what great leadership behaviour looks and feels like. It is intended to influence the user to notice positive examples of leadership in action so the action is easy to practise again in future.

For some, formal training is helpful to support their leadership learning journey. The NHS Leadership Academy is well known for its flagship programmes, designed to support healthcare workers from the start of their careers all the way to board positions. The Edward Jenner Programme is the first port of call if you are looking to build a strong foundation of leadership skills that can help enhance your confidence and competence in your role. The programme has been designed to offer flexibility – the modules are free to access and based online.

In addition to formal learning, there are several other leadership learning resources that are free to access online:

• Bitesize Learning offers short guides, developed by experts, that are an hour or less in length. Topics include courageous conversations, creating time to share ideas and team working.

• The Inspiration Library contains podcasts, videos and blogs on a wide range of topics.

• #ProjectM is a place and space for team leaders and managers to connect, share and learn together. ProjectM is free to access and many of its conversations are facilitated over social media.

• Executive Suite is a range of opportunities for senior leaders to access support and development for themselves and to help them support the development of their staff into the future.

What are the leadership takeaways?

After reading this article, ask yourself if you have ever taken the time to think of yourself as a leader. Have you held up that leadership mirror and asked yourself what type of leader you are? How would people describe you? Do you know what your values are? Do you live by them every day, even in the most challenging of times? If not, why? What stops you?

Have you been on an inclusive leadership journey, and do you recognise your own privilege in life and in the system in which you work? Are you anti-racist and do you have zero tolerance for any form of discrimination? If you see and hear discriminatory behaviours, do you act? Do you lead with compassion and attend, understand, empathise and help others you work alongside? Do you create cultures that are safe, where everyone feels like they belong, and people can bring their authentic selves to work? Do you lead by example, show your vulnerabilities and role model the values you want to see in others?

And, maybe most importantly, do you show yourself the compassion you show others? Compassionate leadership starts from within by being kind to ourselves, non-judgmental, practising self-care and knowing our boundaries. Only when we care for ourselves can we care for others around us, and this is something we all need to remember.

Rachael Moses is a Consultant Respiratory Physiotherapist; the National Clinical Advisor for Respiratory with the Personalised Care Team NHS England; and the Head of Clinical Leadership Development at the People Directorate, NHS England.

References

1. Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. 2013. London: Stationery Office. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-of-the-mid-staffordshire-nhs-foundation-trust-public-inquiry.

2. Keogh B. Review into the Quality of Care and Treatment Provided by 14 Hospital Trusts in England: Overview Report. 2013. Available at https://www.basw.co.uk/system/files/resources/basw_85333-2_0.pdf.

3. Kirkup B. The Report of the Morecambe Bay Investigation. 2015. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/408480/47487_MBI_Accessible_v0.1.pdf.

4. Dixon-Woods M, Baker R, Charles K, Dawson J, Jerzembe, G, Martin G, McCarthy I, McKee L, Minion J, Ozieranski P, Willars J, Wilkie P and West M. Culture and behaviour in the English National Health Service: overview of lessons from a large multimethod study. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2014. 23 (2), 106-115.

5. West M. Compassionate Leadership: Sustaining Wisdom, Humanity and Presence in Health and Social Care. 2021. Swirling Leaf Press. London.

6. Cole-King A and Gilbert P. Compassionate care: the theory and the reality. Holistic Healthcare. 2011. 8(3) 29-37.

7. West M, Bailey S and Williams E. The Courage of Compassion: Supporting Nurses and Midwives to Deliver High-Quality Care. 2020. The King’s Fund, London. Available at https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-09/The%20courage%20of%20compassion%20full%20report_0.pdf.

8. Bailey S and West M. What is Compassionate Leadership? 2022. The King’s Fund. London. Available at https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/what-is-compassionate-leadership.

9. Atkins P and Parker S. Understanding individual compassion in organizations: the role of appraisals and psychological flexibility. Academy of Management Review. 2012. 37. 524-546.

10. Bécares L. Experiences of Bullying and Racial Harassment Among Minority Ethnic Staff in the NHS. Better health briefing paper 14. 2008. Available at https://raceequalityfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/health-brief14.pdf.

11. Ford M. Concern over rate of disabled NHS staff being referred for performance review. Nursing Times. 11 May 2022. Available at https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/workforce/concern-over-rate-of-disabled-nhs-staff-being-referred-for-performance-review-11-05-2022/.

12. GLADD and British Medical Association. Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Medical Profession. 2022. Available at https://www.bma.org.uk/media/6340/bma-sogi-report-2-nov-2022.pdf.

13. Lee SE and Dahinten VS. Psychological safety as a mediator of the relationship between inclusive leadership and nurse voice behaviors and error reporting. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2021, 53, 747–755. Available at https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12689.