Vague symptoms cancer pathway

The role of a diagnostic radiographer in designing a vague symptoms cancer pathway

Cancer is diagnosed through several routes in the UK1. The recent publication from the National Disease Registration Service (NRDS) showed that in 2016, 18% of cancers were diagnosed by emergency presentation while 40% were diagnosed by two-week wait pathways.

In 2016, the two-week wait pathways in the UK were designed around the organ-specific presentation of cancer as described by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines2.

Evidence was emerging, on an international level, that there were “vague” symptoms that merit investigation and that many patients diagnosed with cancer did not have symptoms that would meet the NICE Guidelines 2012 (NG12) referral criteria3. The work of Ingeman et al.4 illustrated three different approaches to managing patients with a vague symptom presentation and evidenced a 16.8% conversion rate to a cancer diagnosis with full investigation.

Cancer Research UK, Macmillan Cancer Support and NHS England (NHSE) established the Accelerate, Coordinate, Evaluate (ACE) programme to fund the establishment of pathways to investigate vague symptoms cancer pathways to evaluate their merit, with the vision that these pathways could potentially reduce the number of patients diagnosed via an emergency route5. Oxfordshire’s Suspected CANcer (SCAN Pathway) was established in March 2017 as one of the ACE sites and was adopted as standard of care in April 2020.

New role for a radiographer

It is widely acknowledged that radiology plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis of many diseases and pathologies, including cancer6. Traditionally, the role of the diagnostic radiographer has been built around the acquisition of diagnostic images and the role of the radiology department tends to be that of a clinical support service. The demand on radiology services has been increasing exponentially over the past 10 years, and that demand has not been met with a growth in either reporting or scanning capacity. This has led to many service users experiencing a delay7.

The success of the cancer nurse specialist role has been key in supporting cancer services and patients8. When planning the SCAN Pathway, it was hoped that a similar role could be developed. As the SCAN Pathway focuses on the early stage of a cancer journey and involves diagnostic tests, it was suggested that this role could be held by a radiographer. Creating a role like this for a diagnostic radiographer was a unique opportunity to expand the scope of advanced practice into a different area of clinical practice.

Diagnostic radiographers tend to advance their practice within an imaging modality or in a reporting role. At the time of establishing the pathway, the team was not aware of another diagnostic radiographer working in a clinical assessment and cancer support role. The diversification of the diagnostic radiographer’s role is in keeping with the Interim NHS People Plan9.

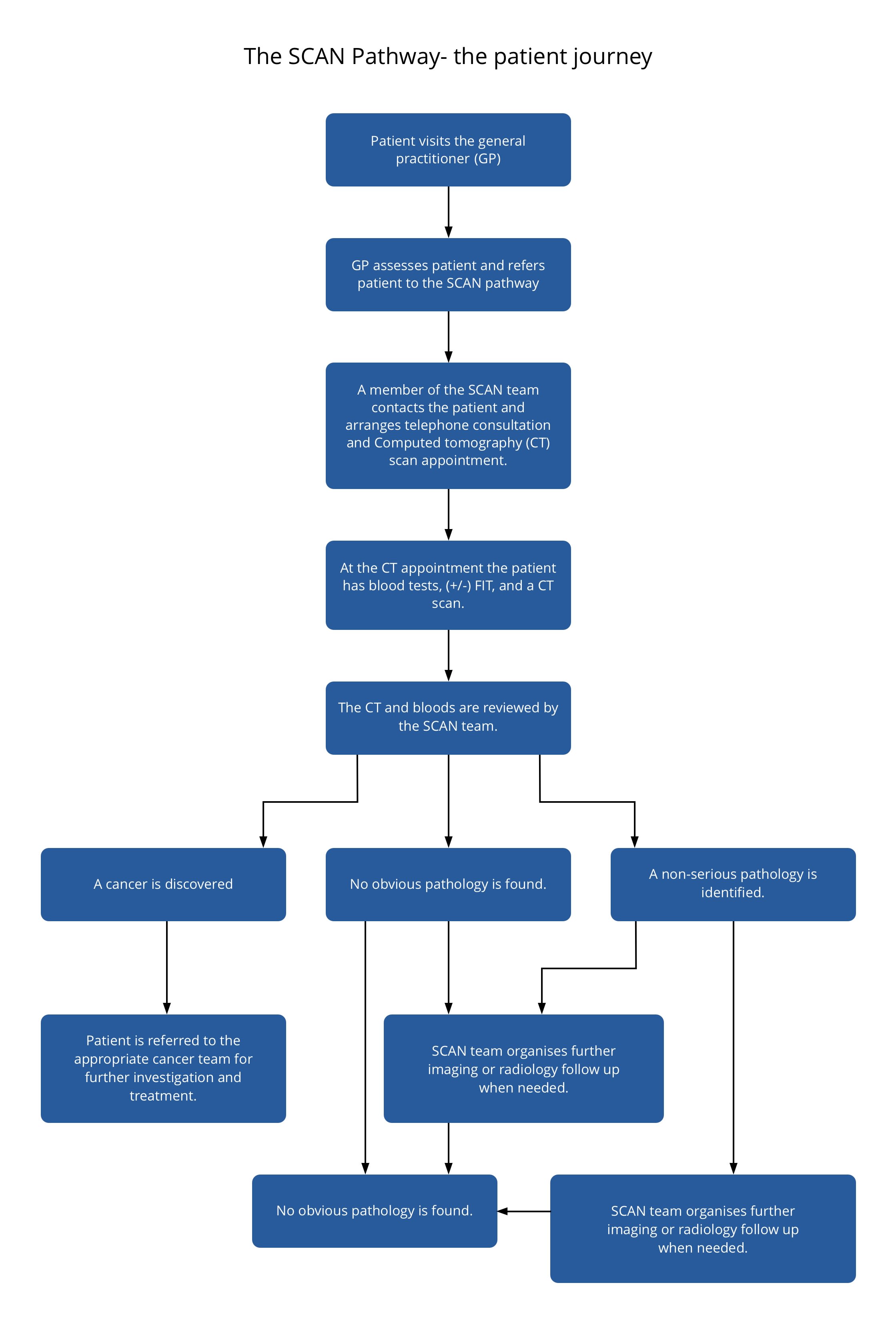

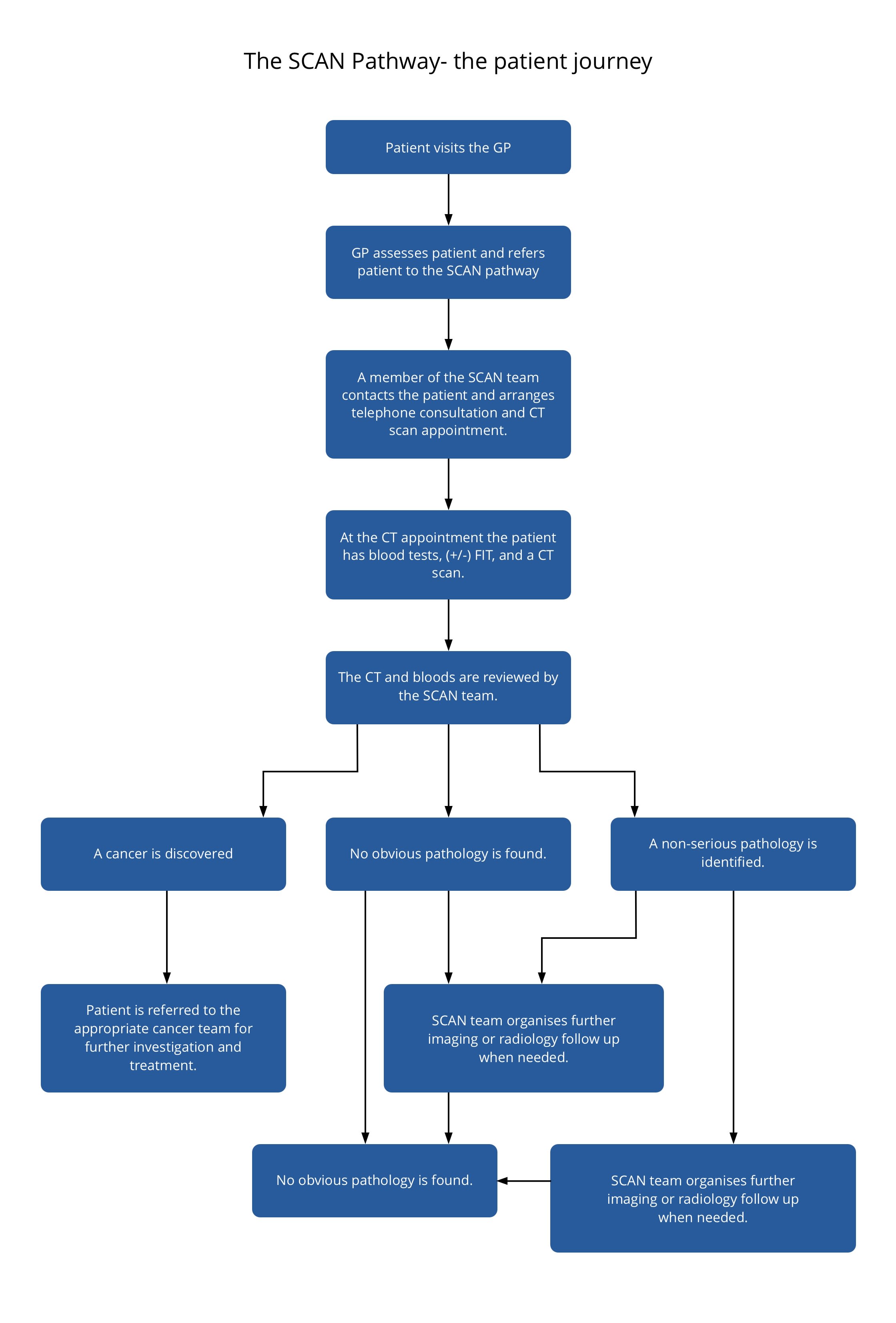

The patient journey through the SCAN Pathway is demonstrated in Figure 1. As illustrated, the navigator is essential throughout the patient journey. The primary focus is communication. The navigator is responsible for communicating with patients and healthcare professionals in both a primary and secondary care setting.

Figure 1

The initial interaction with the patient is arranging the computed tomography (CT) appointment, answering questions about the referral, and onward process of investigation. For many patients, this can be quite distressing as the nature of and rationale for the referral might not have been understood. As radiographers, we encounter patients in a variety of situations and in varying stages of health. Usually, radiographers must build a rapport with patients quickly. This skill is transferrable and essential when working as a navigator.

As part of the training programme for working within SCAN, all navigators undertake a two-day course in advanced communication. This enhances the skills that we already possess and teaches tools to deal with a variety of challenging or difficult conversations. This is employed throughout the patient’s journey through SCAN and is also helpful when communicating with the wide variety of clinicians and healthcare professionals with whom we work.

It is widely acknowledged that radiology plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis of many diseases and pathologies, including cancer6. Traditionally, the role of the diagnostic radiographer has been built around the acquisition of diagnostic images and the role of the radiology department tends to be that of a clinical support service. The demand on radiology services has been increasing exponentially over the past 10 years, and that demand has not been met with a growth in either reporting or scanning capacity. This has led to many service users experiencing a delay7.

The success of the cancer nurse specialist role has been key in supporting cancer services and patients8. When planning the SCAN Pathway, it was hoped that a similar role could be developed. As the SCAN Pathway focuses on the early stage of a cancer journey and involves diagnostic tests, it was suggested that this role could be held by a radiographer. Creating a role like this for a diagnostic radiographer was a unique opportunity to expand the scope of advanced practice into a different area of clinical practice.

Diagnostic radiographers tend to advance their practice within an imaging modality or in a reporting role. At the time of establishing the pathway, the team was not aware of another diagnostic radiographer working in a clinical assessment and cancer support role. The diversification of the diagnostic radiographer’s role is in keeping with the Interim NHS People Plan9.

The patient journey through the SCAN Pathway is demonstrated in Figure 1. As illustrated, the navigator is essential throughout the patient journey. The primary focus is communication. The navigator is responsible for communicating with patients and healthcare professionals in both a primary and secondary care setting.

Figure 1

The initial interaction with the patient is arranging the CT appointment, answering questions about the referral, and onward process of investigation. For many patients, this can be quite distressing as the nature of and rationale for the referral might not have been understood. As radiographers, we encounter patients in a variety of situations and in varying stages of health. Usually, radiographers must build a rapport with patients quickly. This skill is transferrable and essential when working as a navigator.

As part of the training programme for working within SCAN, all navigators undertake a two-day course in advanced communication. This enhances the skills that we already possess and teaches tools to deal with a variety of challenging or difficult conversations. This is employed throughout the patient’s journey through SCAN and is also helpful when communicating with the wide variety of clinicians and healthcare professionals with whom we work.

History-taking skills

Clinical oversight is provided by geratology and general medical consultants. To limit the number of patient visits to hospital, navigators are asked to take a clinical history from all patients. This history-taking encounter can happen via telephone or face to face, depending on the patient’s needs or preference. Taking a detailed and accurate clinical history can be a difficult task. I undertook postgraduate training in advanced clinical practice. This is taught at a number of universities and is usually studied by nurses and other allied health professionals. I was the first diagnostic radiographer to complete this course at Oxford Brookes University.

The material covered is wide ranging and, to gain competency, it is expected that the students will spend time in a range of clinical settings under the supervision of senior medical staff. This was difficult to achieve within radiology, given the transactional nature of the patient encounters and the role of medical staff in radiology. Therefore, I spent time working with the geratology and general medical teams in clinic, ward rounds and acute care settings.

This was extremely beneficial not only for consolidation of the history-taking skills but also for understanding the wider hospital network and the referral routes to different specialities. At times this was difficult, as other medical professionals had their own expectations of the role of a diagnostic radiographer. It was important that I was open to their concerns and used the opportunity to challenge the preconceptions in a constructive manner. It became mutually beneficial because, when planning investigations for patients, I could advise on the most appropriate imaging modality and could teach the other team members what the patient would experience on each occasion.

Interprofessional collaboration

I view participation within interprofessional teams in both a “fleeting” and an established setting as crucial to my role as an advanced practitioner. Interprofessional collaboration promotes understanding and encourages professionals to adopt this sharing of perspective10. To do this, we must set aside some of the indoctrinated and unconscious habits that we develop in our professions and move to include the attitudes and opinions of other professions within our practice11.

Each professional is limited by being a human. Therefore, no one person can possibly know or have the skills to fulfil all the needs of a patient; the only way to achieve holistic care is to openly acknowledge the skills and use other professions in the delivery of care12. By adopting interprofessional working, we are able to ensure that we do everything within our professional power to give patients the best care.

Awareness of your scope of practice

I also found that patients were unsure of my role and whether I was qualified to care for them. It is imperative when we interact with patients that we introduce our role fully, reassuring patients of the scope of our practice and the clinical oversight that is in place to ensure that they are cared for appropriately. This is also important for the navigators. Awareness of your own scope of practice and the knowledge of who to contact when you need support allows you to practise safely.

The responsibility of an advanced practice role was daunting, particularly as I was not aware of another radiographer undertaking this type of practice. The continued support provided by the medical teams has been key in the development of this role and in building my confidence in working in an internally new area of practice.

Developing a CT protocol

CT is used in a variety of clinical scenarios and most patients diagnosed with cancer will have staging completed using this modality6. Some 5,833,620 CT scans were performed across the UK between 2018 and 201913. CT scans may involve using iodinated contrast. It is considered best practice for UK-based radiology departments to use safety questionnaires before this injection, which includes an estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) within the last three months14.

The CT performed in the SCAN Pathway is a contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis (CTCAP). Given the nature of the vague symptoms that patients present with, we wanted to ensure they were not receiving an unnecessary radiation or contrast dose. We were also conscious that some of these patients would have to undergo other investigations, some of which would potentially carry an additional burden of ionizing radiation.

A local protocol was developed with the help of the medical physics department to lower the dose of the CTCAP while maintaining the diagnostic quality of the images. Before undertaking my role within SCAN, I had worked as a clinical radiographer for five years in a tertiary centre undertaking CT, general X-ray, fluoroscopy, and interventional radiology and cardiology procedures. As a diagnostic radiographer, my knowledge of the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2017 (IR[ME]R 2017) and familiarity with practising within them was essential in developing the local protocol15.

Following the telephone consultation, navigators meet the patient at the CT appointment. This serves a dual purpose. Primarily, as a diagnostic radiographer, I can perform the CT scan. The advantage of having a radiographer in this role is that it enables CT appointments to be more flexible and we have been able to accommodate weekend and evening appointments outside of those usually offered. This has been beneficial to patients who are working or have other commitments that make daytime appointments difficult to attend, therefore the “did not attend” rates for the pathway are anecdotally low.

We wanted to design a service that offered holistic care, and having the navigator meet patients at the CT appointment offers a continuity of care that would be difficult to achieve if this service were not based within radiology. The benefits of this example of continuity of care have yet to be published. Locally, we designed patient feedback questionnaires and 97% of our patients felt that the continued interaction with the same professional made them feel more reassured.

From the viewpoint of a navigator, it is helpful to meet your patient because you can clarify any uncertainties raised in the clinical history and it provides a different perspective on the patient’s health and wellbeing, which can be difficult to achieve over the telephone.

Vetting referrals

As part of their role, navigators are also expected to vet the referrals. The referrals are completed by the GP in a proforma that has been standardised, alongside the other two-week wait referral pathways. Vetting the referrals ensures that the patient would not be better served by a different pathway and that the exposure to ionizing radiation is justified15.

To do this safely, we wrote a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) to guide and train the navigators to vet these referrals appropriately. Combining the skills I have as a radiographer with the newly acquired knowledge of the other two-week cancer pathways enabled me to write a comprehensive SOP.

Like the geratology and general medical clinicians, radiologists have been supportive in creating this SOP and continue to be proactive in assisting with any queries, offering advice to the navigators regarding the referrals and any following investigations patients may have after the initial CTCAP.

Breaking bad news

For most patients, their journey through the SCAN Pathway concludes with the results of the CT scan. To provide continuity of care, these results are explained by the navigator. The discussion of the results can happen via telephone or face to face, depending on the complexity of the result and the patient’s preference. The advanced communication training skillset is of vital importance when approaching this conversation. Breaking bad news can be challenging and not one that I was familiar with before my role in the SCAN Pathway.

I shadowed the acute oncology team to gain experience of this from a clinician’s perspective. I learned the importance of using simple terms and gained awareness of how too much information can be overwhelming. Managing the emotional reaction of the patients and their loved ones in a compassionate and professional manner is imperative. When establishing the navigator role, links were made with the organ-specific teams and the support networks available for patients. This collaborative approach enables the navigators to safely signpost these patients to the next steps or the additional support they may need.

I feel that diagnostic radiographers are ideally placed to develop and run services with an imaging focus. The opportunity offered by creating a service such as this has allowed me to grow my clinical knowledge and communication skills, and diversify my practice. It has enabled me to design a patient-centric service that aims to deliver holistic care. As healthcare professionals, that is all we can ever hope to achieve for our patients. Although challenging at times, I would urge any radiographers or radiology departments to seize any opportunity to do something like this.

Julie-Ann Moreland is Macmillan and Right By You Project Manager and SCAN Pathway Navigator at Churchill Hospital, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust.

References

1. NHS. CancerData. Routes to diagnosis: tumours diagnosed 2006-2016. Available at www.cancerdata.nhs.uk/routestodiagnosis/routes. Accessed 10 January 2023.

2. National Collaborating Centre for Cancer and NICE. NG12. Suspected Cancer – Recognition and Referral. NICE Guideline. 2015. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-2676000277. Accessed 11 January 2023.

3. Neal RD, Din NU, Hamilton W, Ukoumunne OC, Carter B, Stapley S and Rubin G. Comparison of cancer diagnostic intervals before and after implementation of NICE guidelines: analysis of data from the UK General Practice Research Database. Br J Cancer. 4 February 2014; 110(3): 584-92. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.791. Epub 24 December 2013. PMID: 24366304; PMCID: PMC3915139.

4. Ingeman ML, Christensen MB, Bro F et al. The Danish cancer pathway for patients with serious non-specific symptoms and signs of cancer – a cross-sectional study of patient characteristics and cancer probability. BMC Cancer. 2015. 15, 421. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1424-5.

5. Cancer Research UK. Accelerate, Coordinate, Evaluate (ACE) programme. 2017. Available at http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/early-diagnosis-activities/ace-programme. Accessed 10 January 2023.

6. Nass S J, Cogle CR, Brink JA, Langlotz CP, Balogh EP, Muellner A, Siegal D, Schilsky RL and Hricak H. Improving cancer diagnosis and care: patient access to oncologic imaging expertise. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019. 37, no. 20 1690-1694.

7. NHS England and NHS Improvement. Transforming Elective Care Practices – Radiology. Available at www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/radiology-elective-care-handbook.pdf. Accessed 11 January 2023.

8. Kerr H, Donovan M and McSorley O. Evaluation of the role of the clinical nurse specialist in cancer care: an integrative literature review. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2021. 30, 3. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13415.

9. NHS. Interim NHS People Plan 2019. Available at www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Interim-NHS-People-Plan_June2019.pdf. Accessed 11 January 2023.

10. Nancarrow SA, Booth A, Ariss S, Smith T, Enderby P and Roots A. Ten principles of good interdisciplinary team work. Human Resources for Health. 2013. 11(19) doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-19.

11. Best S and Williams S. Integrated care: mobilising professional identity. Journal of Health Organization and Management 2018. 32(5) pp.726-740. https://doi-org.oxfordbrookes.idm.oclc.org/10.1108/JHOM-01-2018-0008.

12. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Developing Professional Identity in Multi-Professional Teams. 2020. London. Available at https://www.aomrc.org.uk/reports-guidance/developing-professional-identity-in-multi-professional-teams/. Accessed 11 January 2023.

13. NHS England and NHS Improvement. Diagnostic imaging dataset statistical release. 2020. Available at www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/01/Provisional-Monthly-Diagnostic-Imaging-Dataset-Statistics-2020-01-23.pdf. Accessed 15 January 2023.

14. The Royal College of Radiologists. Standards for Intravascular Contrast Administration to Adult Patients. 2015. Third edition. Available at www.rcr.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Intravasc_contrast_web.pdf. Accessed 15 January 2023.

15. Department of Health and Social Care. Guidance to the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2017. 2018. Available at https:// assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/ uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/ file/720282/guidance-to-the-ionising-radiationmedical-exposure-regulations-2017.pdf. Accessed 15 January 2023.