FOP: what do radiographers need to know?

To mark Global FOP Awareness Day on 23 April, Synergy speaks to Helen Bedford-Gay, trustee of FOP Friends, about the ultra-rare condition and how radiographers can spot it

By Marese O'Hagan

At seven months pregnant with her son, Oliver, Helen Bedford-Gay had an ultrasound that would reveal a rare condition, one that Helen is now urging radiographers to be aware of. When the sonographer noted that they couldn’t see Oliver’s toes, this was put down to him scrunching them up in the womb. But at 13 months old, Oliver was diagnosed with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), an extremely rare genetic condition that causes unwanted bone growth. Currently, there is no cure.

Because of its extreme rarity, Helen found it difficult to learn more about FOP after Oliver’s diagnosis. So she and her husband, joined by friends and family, founded charity FOP Friends in 2012.

Synergy sat down with Helen to hear about what can trigger a FOP flare-up, what FOP Friends is doing to raise awareness and how radiographers can spot the condition.

1. What is FOP?

FOP is a rare genetic condition affecting around one in a million births. Currently, there is no cure and no available treatment in the UK. There are about 70 known cases in the UK and fewer than 1,000 worldwide. Babies born with FOP typically appear healthy, with the exception of turned in or shortened big toes.

During childhood, usually within the first 10 years, children with FOP experience intermittent episodes of painful soft tissue swelling, known as flare-ups. These episodes can be triggered by seemingly minor things such as bumps and bruises, viral infections, tiredness, intramuscular injections or overstretching muscles.

Over time, FOP causes new bone to form, gradually restricting movement joint by joint. This can eventually lead to complete immobility, sometimes leaving individuals in a fixed, bent posture. When this extra bone forms in the face and mouth muscles, it can also ‘lock’ the jaw, making eating, speaking and even keeping teeth clean very difficult.

Unfortunately, surgery to remove the newly formed bone isn’t an option, because it can actually cause even more bone to grow in that area.

In 2024, the first treatment for FOP, Sohonos, received approval in several countries including America, Canada and Australia. However, it didn’t receive regulatory approval from the European Medicines Agency and, as a result, no application was filed for the UK. However, active research and clinical trials offer those living with FOP much-needed hope.

2. When examining an X-ray, what signs of FOP should radiographers look out for?

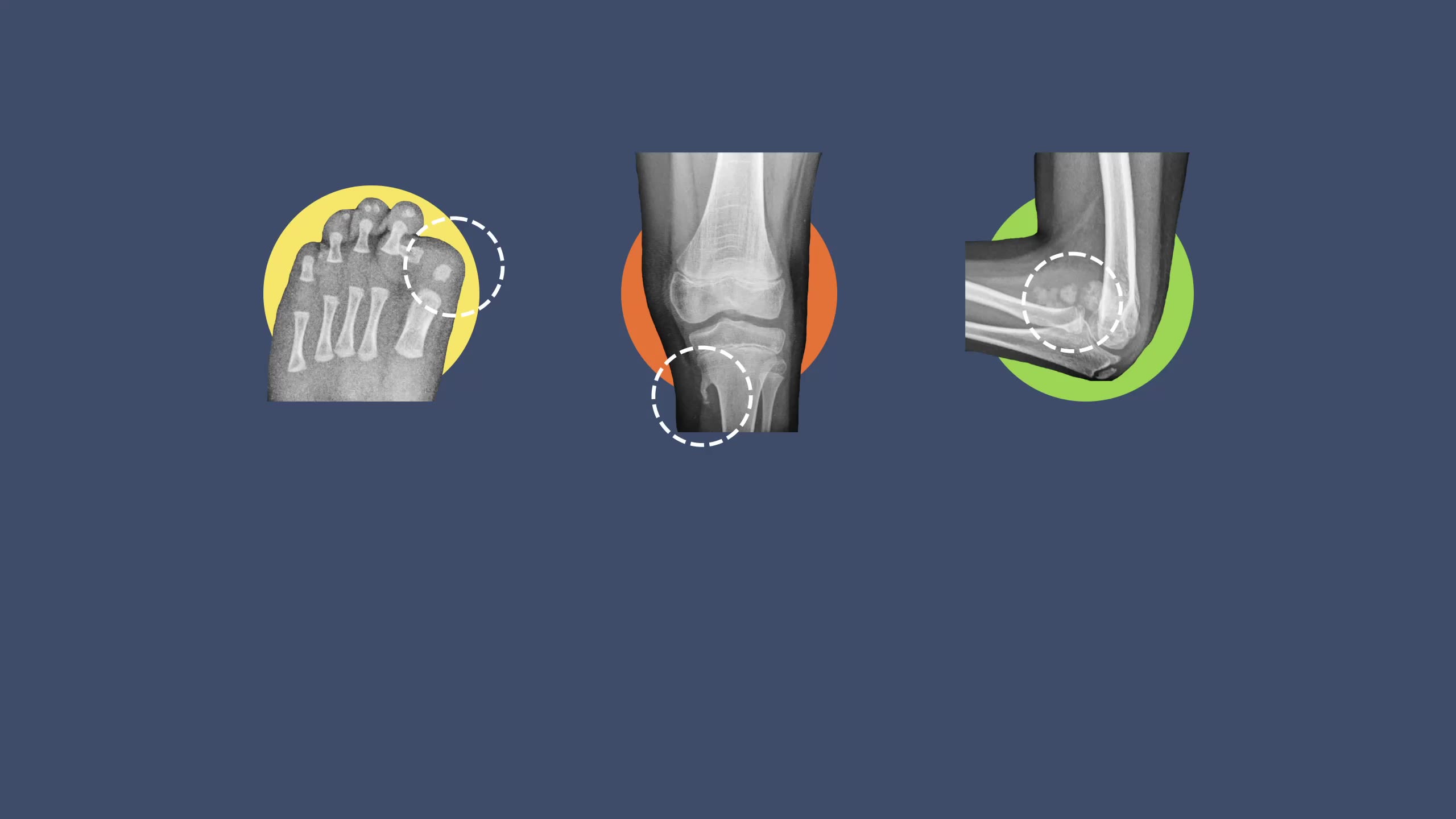

One of the key features of FOP is the shortened, turned in or missing big toes. The ‘FOP toes’ are usually visible at birth and can be noted from a quick, visual check. Babies who present with these toes are often misdiagnosed as having ‘baby bunions’ or hallux valgus. An X-ray of FOP toes can often show several very specific abnormalities, ranging from shortening, malformation or a missing joint in the great toe. Babies with FOP can also present with shortened thumbs, which also may be missing a joint.

Before he was diagnosed, Oliver was assumed to have some form of hallux valgus and steps were taken to try and ‘straighten them’. He was given tiny soft toe splits to attempt to correct them, which obviously never worked. Oliver received his diagnosis before any surgical intervention for his toes, which in retrospect was incredibly lucky.

People living with FOP experience unexplained swellings that can appear anywhere on the body, either because of trauma or spontaneously. They are often misdiagnosed as cancer, which can result in unnecessary and harmful biopsies or surgeries. In babies, they often get soft lumps that spontaneously appear on the skull. These lumps can move around and last for some time. In some cases, they subside, in others they leave new bone formation in the scalp or around the skull. It was an unexplained lump that appeared on the back of Oliver’s head, at around three months of age, which ultimately led to his diagnosis.

In our case, we were told that it wasn’t cancer, but because of his age they wouldn’t biopsy. They would simply remove it. At nine months old, Oliver underwent neurosurgery to have the lump removed. A few months later, a junior doctor connected the unexplained swelling with the funny toes and proposed the diagnosis of FOP. This is why awareness among medical professionals is critical.

Babies with FOP are often born with fused vertebrae in the cervical spine. Depending on the degree of fusion, this can affect their ability to move their neck. It’s for this reason that babies with FOP rarely crawl. Oliver never crawled when he was a baby, but this was before his diagnosis, so we just assumed it was a milestone he would bypass. We also noticed that as Oliver got older and enjoyed watching planes like all young children do, he would have to tilt his whole body backwards to look up to the sky, as he was unable to bend his neck. Looking back at family photos now, all the signs were there.

When FOP hasn’t been diagnosed, surgery may be suggested to correct the malformations. It is crucial to understand, however, that surgery for someone with FOP carries a significant risk of accelerating FOP progression and should therefore be avoided unless absolutely necessary. In Oliver’s neurosurgery case, for no known reason – such is FOP – his surgery was uneventful and there was no FOP response.

One of the key features of FOP is the shortened, turned in or missing big toes. The ‘FOP toes’ are usually visible at birth and can be noted from a quick, visual check. Babies who present with these toes are often misdiagnosed as having ‘baby bunions’ or hallux valgus. An X-ray of FOP toes can often show several very specific abnormalities, ranging from shortening, malformation or a missing joint in the great toe. Babies with FOP can also present with shortened thumbs, which also may be missing a joint.

Before he was diagnosed, Oliver was assumed to have some form of hallux valgus and steps were taken to try and ‘straighten them’. He was given tiny soft toe splits to attempt to correct them, which obviously never worked. Oliver received his diagnosis before any surgical intervention for his toes, which in retrospect was incredibly lucky.

People living with FOP experience unexplained swellings that can appear anywhere on the body, either because of trauma or spontaneously. They are often misdiagnosed as cancer, which can result in unnecessary and harmful biopsies or surgeries. In babies, they often get soft lumps that spontaneously appear on the skull. These lumps can move around and last for some time. In some cases, they subside, in others they leave new bone formation in the scalp or around the skull. It was an unexplained lump that appeared on the back of Oliver’s head, at around three months of age, which ultimately led to his diagnosis.

In our case, we were told that it wasn’t cancer, but because of his age they wouldn’t biopsy. They would simply remove it. At nine months old, Oliver underwent neurosurgery to have the lump removed. A few months later, a junior doctor connected the unexplained swelling with the funny toes and proposed the diagnosis of FOP. This is why awareness among medical professionals is critical.

Babies with FOP are often born with fused vertebrae in the cervical spine. Depending on the degree of fusion, this can affect their ability to move their neck. It’s for this reason that babies with FOP rarely crawl. Oliver never crawled when he was a baby, but this was before his diagnosis, so we just assumed it was a milestone he would bypass. We also noticed that as Oliver got older and enjoyed watching planes like all young children do, he would have to tilt his whole body backwards to look up to the sky, as he was unable to bend his neck. Looking back at family photos now, all the signs were there.

When FOP hasn’t been diagnosed, surgery may be suggested to correct the malformations. It is crucial to understand, however, that surgery for someone with FOP carries a significant risk of accelerating FOP progression and should therefore be avoided unless absolutely necessary. In Oliver’s neurosurgery case, for no known reason – such is FOP – his surgery was uneventful and there was no FOP response.

3. Why did you establish FOP Friends? And what does the charity do?

When we received Oliver’s diagnosis, the neurosurgeon wrote ‘fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva’ on a piece of paper and told us he would need to avoid rugby. But that was it, and we were sent on our way. We weren’t signposted to a charity to help us. We managed to find the International FOP Association, and through them we were able to connect with others who understood and would quickly become our support network.

In time, we found other families in the UK who were actively fundraising for the research team at Oxford University, so we got involved with them. We started holding more fundraisers and learning more about the condition. It slowly dawned on us that becoming a registered charity would be the key to getting bigger funding for the research team.

We soon found newly diagnosed families were getting in touch with us, and we began signposting them to the medical specialists and connecting people. We didn’t want them to be alone like we had been. In 2014, we held our first conference and invited the world’s FOP specialists. It was then that we established ourselves as the UK FOP charity. Now, we are recognised and respected both in the UK and beyond. In 2022, I was honoured to receive a British Empire Medal in recognition of my services to charity in Queen Elizabeth II’s Jubilee Honours List.

We keep our FOP Friends families updated with everything going on in the world of FOP and ensure they know where to find the information they need. We also advocate for those living with FOP, attending events in the UK and abroad. FOP Friends is one of the founding charities of the Adult Rare Bone Disease Collaborative Network.

We hold the conference every two years, welcoming people from around the world. They have a research and medical focus, with the opportunity for patients to have a consultation with the world’s FOP specialists.

We have also held two family weekends at Center Parcs and are excited to be hosting our first family weekend post-Covid at West Midlands Safari Park. This will be a fun weekend with many of our families, giving them the opportunity to hang out and spend time with people who truly understand the journey they are on and the challenges they face daily. The weekend will be all about fun and friendship, making connections that will make the dark days seem a little brighter.

4. Global FOP Awareness Day takes place on 23 April. How does FOP Friends raise awareness of FOP on this day?

We have been raising awareness of FOP throughout April for nearly 10 years. We run our #FunFeet4FOP campaign, inviting people to wear funny socks or silly shoes or even get creative and decorative their toes, and then share photos of their fun feet on social media. It’s all about raising awareness of the key diagnostic feature – the toes. It’s great seeing how creative people get but, to be honest, the most popular ones are always dogs in socks!

We also share facts about FOP throughout the month to educate people about the condition. We want to raise awareness of the medical facts – how simple daily tasks such as putting socks on or brushing one’s hair can be challenging or impossible for someone with FOP – but also celebrate the achievements of those living with FOP. People are more than their diagnosis.

FOP doesn’t affect intelligence, and those living with the condition go on to have fulfilling lives; they are just constantly finding new ways to adapt to their changing mobility. Oliver is a testament to that. He has recently received his Young Leader Award from Scouts and his Silver Duke of Edinburgh Award, and has just started on his gold. He is determined to do his very best, despite what FOP is putting him through. We are all incredibly proud of him and all he has achieved already.

5. What do you want radiographers to know about those living with FOP?

There are so many ways FOP may present and, for many of those, a sonographer or radiographer may be the first person to notice. From the funny toes to the shortened thumbs, to ultrasounds or unusual osteochondromas on the knees, there are red flags everywhere. The wonderful people at Medics for Rare Disease explain it best: if you hear hooves, think zebra! If you see funny toes, think FOP, not bunions!

The UK’s specialists, Professor Richard Keen and Dr Judith Bubbear at the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital, are always able to advise if you suspect FOP. Pausing for confirmation could avoid unnecessary invasive treatments which, if the patient does in fact have FOP, could cause irreparable damage resulting in the irreversible loss of movement for someone. With a prevalence of one in a million, it’s unlikely you’ll ever see the toes, but some of you will. And if by reading this article, looking at the images, it prevents even just one person from being misdiagnosed, then I’ll have done my job.

More about FOP Friends

FOP Friends is a registered charity that supports research into FOP and related conditions. The charity runs conferences and events aimed at sharing information about FOP and connecting FOP families with experts in the field. They also advocate for those living with FOP, both nationally and globally, including within parliament.

FOP Friends provides crucial support and connections for families navigating this journey, as well as fundraises to support research into treatments and a cure.

To learn more about their work, visit fopfriends.com

Read more