Profile

Adventures in ultrasound – Julie Burnage on the business world, learning from mistakes and Lillie the ‘phantom’ dog

Radiographer Julie ran into stumbling block after stumbling block throughout her career, but sheer perseverance – and a few leaps of faith – saw her come out on top. Synergy profiles Julie’s career

By Marese O'Hagan

Julie Burnage

Julie Burnage

To emphasise the uniqueness of Julie Burnage’s career, it is perhaps best to start with where she is today and with Lillie. Lillie is a dog. Well, kind of…

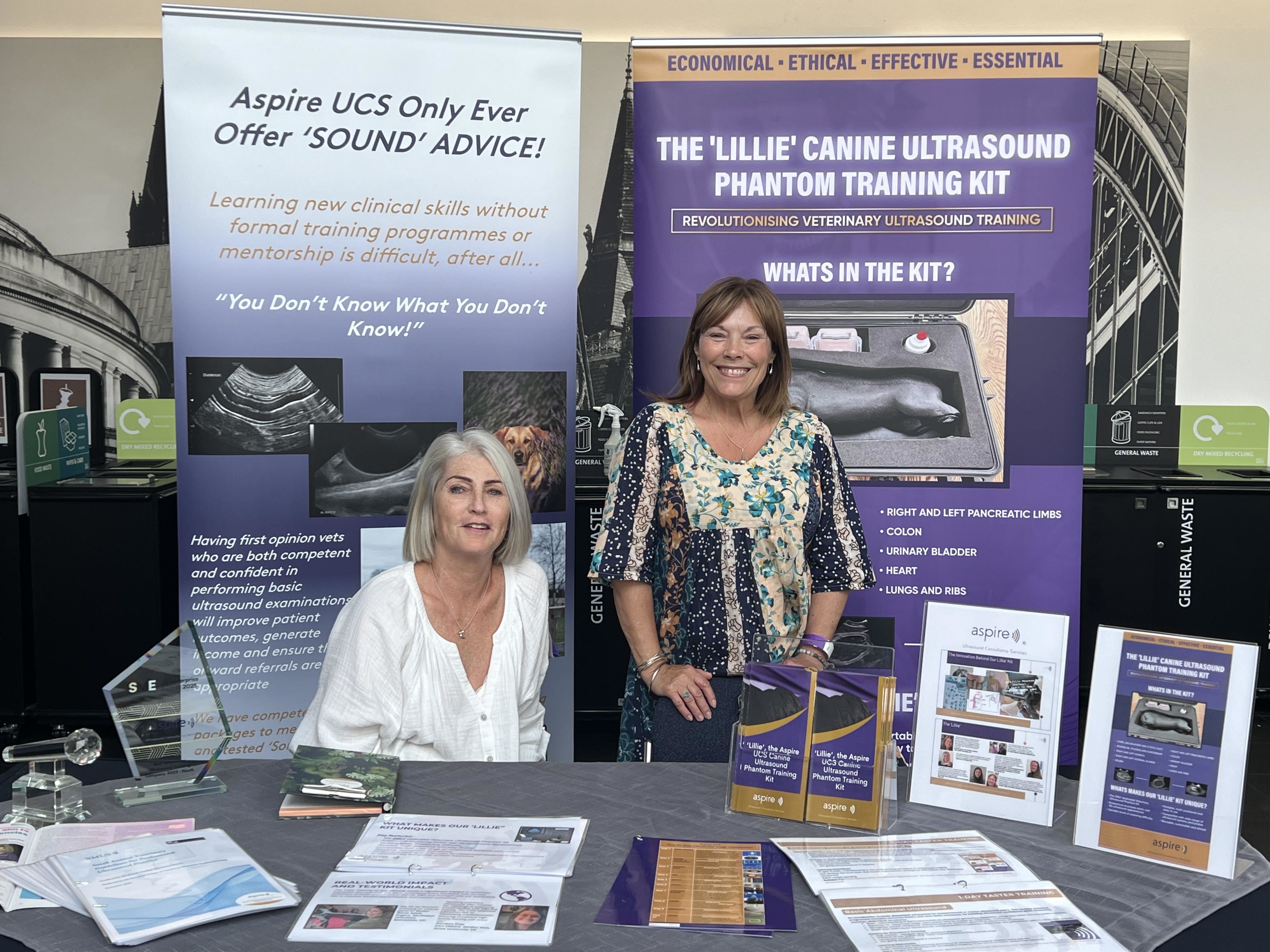

Lillie is a canine ultrasound training tool; a torso complete with tissue-mimicking internal organs such as the liver, gallbladder, adrenal glands, GI tract, kidneys and great vessels. It was designed by Aspire Ultrasound Consultancy Services (a company founded in 2017 by Angie Lloyd-Jones who persuaded Julie to join her as a director in 2020) to support small animal ultrasound training for veterinary surgeons and nurses.

In human medicine, there is the opportunity to train on patient volunteers and most of them are compliant and do not bite if they don’t want to be scanned – the same cannot be said for cats and dogs.

For Julie, it has been a maze-like career journey that led her from diagnostic radiography to ultrasound, mammography, teaching, back to ultrasound, to business creation and then to veterinary ultrasound and Lillie. Synergy spoke with Julie to explore her unique path through the world of radiography.

Julie Burnage

Julie Burnage

To emphasise the uniqueness of Julie Burnage’s career, it is perhaps best to start with where she is today and with Lillie. Lillie is a dog. Well, kind of…

Lillie is a canine ultrasound training tool; a torso complete with tissue-mimicking internal organs such as the liver, gallbladder, adrenal glands, GI tract, kidneys and great vessels. It was designed by Aspire Ultrasound Consultancy Services (a company founded in 2017 by Angie Lloyd-Jones who persuaded Julie to join her as a director in 2020) to support small animal ultrasound training for veterinary surgeons and nurses.

In human medicine, there is an opportunity to train on patient volunteers and most of them are compliant and do not bite if they don’t want to be scanned – the same cannot be said for cats and dogs.

For Julie, it has been a maze-like career journey that led her from diagnostic radiography to ultrasound, mammography, teaching, back to ultrasound, to business creation and then to veterinary ultrasound and Lillie. Synergy spoke with Julie to explore her unique path through the world of radiography.

Radiography seed planted early

Julie first knew she wanted to be a radiographer when she was in the last year of primary school, she tells Synergy. “I had my leg X-rayed and I just thought ‘this job looks alright’,” she says. “And I remember asking the radiographer: ‘Do you like your job and do you get paid well?’ And she said: ‘Yeah, it’s quite good.’ And I was hooked. I never wanted to do anything else.”

In the 1980s, radiography was not a degree course, which meant that the hospital chose their students (rather than the university, as happens now). So Julie started to do voluntary work every week in the X-ray department of Tameside General, Ashton-Under-Lyne – her local hospital – to show her determination.

After qualifying there as a radiographer in 1985, she job shared for a short while with the two girls she had trained with until she got a job at Wythenshawe Hospital: a cardiothoracic and major trauma centre close to Manchester airport. “I absolutely loved it. I loved the variety –theatre, portables, the A&E stuff, the fast-paced exciting things,” she says.

But a subsequent move to North Wales made the commute to and from Manchester every day exhausting and, when a job came up at Glan Clwyd Hospital, Julie applied and started work there in 1987. The differences in the ways of working came as a shock because moving from a busy, fast-paced specialist hospital to what felt almost like a provincial hospital seemed like a backwards step.

By this time Julie had decided she wanted to progress to a Senior 2 radiographer role – in a time before Agenda for Change banding – but the only way to do this was either “dead men’s shoes’, or to train in a specialty”. CT didn’t appeal to her: “It felt to me like it was all about being behind a machine and nothing to do with patient contact, and it was always about the patients and patient contact for me.”

This left ultrasound as the only option. Julie applied for one of two training roles available and, because the superintendent couldn’t come up with a valid reason that she shouldn’t be allowed to do the course, she got one of the posts and qualified in ultrasound in 1990 (Julie remains forever grateful to Vanessa and Michelle for their patience and for sharing their skills and knowledge) – having had her first child in the middle of the training!

Radiography seed planted early

Julie first knew she wanted to be a radiographer when she was in the last year of primary school, she tells Synergy. “I had my leg X-rayed and I just thought ‘this job looks alright’,” she says. “And I remember asking the radiographer: ‘Do you like your job and do you get paid well?’ And she said: ‘Yeah, it’s quite good.’ And I was hooked. I never wanted to do anything else.”

In the 1980s, radiography was not a degree course, which meant that the hospital chose their students (rather than the university, as happens now). So Julie started to do voluntary work every week in the X-ray department of Tameside General, Ashton-Under-Lyne – her local hospital – to show her determination.

After qualifying there as a radiographer in 1985, she job shared for a short while with the two girls she had trained with until she got a job at Wythenshawe Hospital: a cardiothoracic and major trauma centre close to Manchester airport. “I absolutely loved it. I loved the variety –theatre, portables, the A&E stuff, the fast-paced exciting things,” she says.

But a subsequent move to North Wales made the commute to and from Manchester every day exhausting and, when a job came up at Glan Clwyd Hospital, Julie applied and started work there in 1987. The differences in the ways of working came as a shock because moving from a busy, fast-paced specialist hospital to what felt almost like a provincial hospital seemed like a backwards step.

By this time Julie had decided she wanted to progress to a Senior 2 radiographer role – in a time before Agenda for Change banding – but the only way to do this was either “dead men’s shoes’, or to train in a specialty”. CT didn’t appeal to her: “It felt to me like it was all about being behind a machine and nothing to do with patient contact, and it was always about the patients and patient contact for me.”

This left ultrasound as the only option. Julie applied for one of two training roles available and, because the superintendent couldn’t come up with a valid reason that she shouldn’t be allowed to do the course, she got one of the posts and qualified in ultrasound in 1990 (Julie remains forever grateful to Vanessa and Michelle for their patience and for sharing their skills and knowledge) – having had her first child in the middle of the training!

Pursuing her dreams

Julie didn’t end up getting a Senior 2 post. But as she worked, she went to night school and gained a further education teaching certificate because she loved learning, enjoyed teaching the radiography students and wanted to give them the best support she could.

It was around this time that Julie had a bit of an epiphany. “I’d approached one of the radiologists in my hospital about why we didn’t do ultrasound in GP surgeries, because again, coming from Manchester, within a 10-mile radius you’d have four or five hospitals giving patients choice of where to go for their diagnostics and treatment. But where I was in North Wales, the next nearest hospital was 30 miles in either direction.

“I scanned a lady – it had taken her an hour and three quarters to travel the three miles on public transport. So why aren’t we doing this in surgeries? It just seemed to make sense. I was told: ‘It’ll never work. That’s ridiculous. Who’s going to do it? It won’t work.’ And I just remember thinking: ‘I’m flipping sure it will.’”

In protest at not getting the Senior 2 post (and because of a degree of belligerence she says she still has), Julie resigned and was fortunate to then get a job at Breast Test Wales, the Welsh Breast Screening Programme, a role she enjoyed because of the opportunity for patient interaction but also because she met Maggs, who remains one of her closest friends.

But it was in 1995, when she found herself divorced and living on a friend’s (the aforementioned Maggs) drive in a clapped-out caravan without a toilet or running water, that she decided her dream of taking ultrasound scanning to GP surgeries was worth going for. “That’s when I thought ‘I need to set up an ultrasound company’, because I had nothing except the clothes I stood up in so I literally had nothing to lose and maybe I could do it now,” she says.

Shot in the dark

Setting up Ultrasound Now to provide medical (ienon-obstetric) ultrasound scanning in GP surgeries was a leap of faith, and it took a lot of hard work to get going. “I went to the local library – we didn’t have mobiles – got all the phone books out and found the phone numbers of dozens of hospitals,” Julie recalls.

“I went back to my friend’s house and phoned the hospitals to see who had the biggest waiting lists. I lied and pretended my elderly aunt needed the scan and wasn’t sure which hospital she had been referred to.” At the time, some of these waiting lists ranged from 20 to 35 weeks – possibly a good result in some areas nowadays, she points out.

“I then went back to the library, got all the phone books out again and wrote down all the GP names, addresses and phone numbers of those who might be referring to the hospitals with the longest waiting lists. I wrote to them all, and a week later started making cold calls to the practice managers. Although the majority were not interested (because it was 1996 and, after 18 years of Conservatives in power, it was anticipated that there was to be a change of government and, with that, who knew what changes to healthcare), a large practice in North Wales and a consortium of GPs in Stockport gave me my first contracts.”

Eventually, the hard graft (rarely working less than 50 hours a week and spending days at a time away from home) proved worth it. Not only did Ultrasound Now (USN) become a success, but Julie also met her now husband, with whom she celebrated her silver wedding anniversary in June. He joined her at Ultrasound Now and took control of some of the management aspects – “because chaos is how my mind works”, she says. “I am not organised. I will often have five or six tasks on the go at any one time and I cannot focus on any of them! The only time my mind is focused on the job in hand is when I am scanning.”

USN merged with another company in 2013. Julie resigned from the role of director of clinical services at the joint business in 2017 and, when the company was sold in 2020, she resigned from the board of directors.

Because of a non-compete clause Julie could not work for any other ultrasound provider in any capacity (except as a sonographer in the NHS) and, as she had a repetitive strain caused by the intensity of life as a sonographer, there was no way she could go back to scanning.

So she set up JB Imaging Solutions, a company that provides ultrasound audit and training services. Julie spent many hours reading CQC reports and came across one for Marie Stopes International (MSI), where the CQC raised serious concerns about the standards of ultrasound scanning in the service. “I messaged the MD and said: ‘I think you have a serious problem and I can help you sort it out,’” she says. And so started the mammoth task of policy rewrites, audit, competency assessments and attempts to train many people who did not believe they needed to work on their skillset – an attitude that shocked Julie. After 14 months, Julie terminated her contract with MSI.

In 2020, Julie was approached by her long-time friend and former colleague Angie Lloyd-Jones asking if she was bored and fancied joining the veterinary industry. Angie founded Aspire Ultrasound Consultancy Services in 2017. The company provides ultrasound consultancy services to vets and vet nurses and, as well as actually performing scans on behalf of vets, also provides comprehensive training and mentorship programmes. “When Angie asked me if I wanted to do veterinary [ultrasound], I didn’t,” Julie says. “And she said: ‘I’m going to send you some links. I want you to have a look at these as training videos.’

“So I had a look and thought they were fake. They were so bad. And I rang her up and I said: ‘I’m not falling for it. I don’t know how you’ve made these people film things that are so bad, but I’m not falling for it.” And she said: ‘No, they’re real.’

“I just turned to my husband and said: ‘I’m in.”

Angie had a part-time job scanning companion animals and was offered a short-term contract to provide ultrasound to a different specialist small animal hospital in the North East of England. And so, during Covid, they drove the 200 miles each way at the start of every week to stay in an empty hotel (key workers and night watchman only) to scan cats and dogs, with Julie doing her training as they scanned. “I absolutely loved it,” says Julie, “the best bit was being able to cuddle my patients – something I would have been struck off the register for in the human world!”

It was also during Covid that Angie and Julie wrote the British Medical Ultrasound Society Small Animal Ultrasound Guidelines (the first in the world) to provide protocols and guidance to those performing ultrasound scans on companion animals. “We were thrilled when the European College of Veterinary Diagnostic Imagers ratified our guidelines – it felt like they had been ‘rubber stamped’ by the experts,” Julie recalls.

Creating Lillie

Together, Angie and Julie began organising and delivering ultrasound training courses for vets and vet nurses – a resource they found was badly needed. “We met with quite a bit of resistance at first – not being vets and coming along saying we could teach vets – but the naysayers were missing the point. We weren’t trying to teach them how to be vets, we were teaching them how to become better at ultrasound,” says Julie.

“We do 600 hours of training to become a human sonographer – that’s one species. Vets get a half day, one day if they’re lucky, and they’re expected to be able to go out and scan all species. It’s what’s called a day-one competency. The day they qualify, they’re supposed to be able to do an abdominal scan.”

Before phantom dog Lillie entered the picture, these kinds of courses required attendees to bring their own pets to scan. Predictably, this didn’t always go smoothly. “We always bring at least one of our own dogs to the course but you might have 12 dogs running around going crazy, or 12 very grumpy dogs that don’t want to be scanned, and they get tired of lying there and being prodded and poked,” Julie explains. “So we started to talk about a phantom.”

Lillie’s life began ‘on the back of a cigarette packet’ at the London Vet Show. Julie and Angie were speaking to a man who made bladder phantoms for vets to practice cystocentesis, and began drawing diagrammes of what a phantom dog torso would need to be – namely, ultrasound friendly.

Named after Angie’s pet dachshund, Lillie, phantom Lillie went through many prototypes (and three years of trials and tribulations) before it was introduced into Julie and Angie’s teaching. “Lillie isn’t meant to replace training on real animals, but it helps the vets get used to ‘driving the ultrasound machine’ and to work on their hand-eye brain coordination; sliding rocking, rotating the probe and seeing what happens to the image,” Julie continues. “They could then take that skill once they’d fine-tuned it and use it on real patients.”

Creating Lillie

Together, Angie and Julie began organising and delivering ultrasound training courses for vets and vet nurses – a resource they found was badly needed. “We met with quite a bit of resistance at first – not being vets and coming along saying we could teach vets – but the naysayers were missing the point. We weren’t trying to teach them how to be vets, we were teaching them how to become better at ultrasound,” says Julie.

“We do 600 hours of training to become a human sonographer – that’s one species. Vets get a half day, one day if they’re lucky, and they’re expected to be able to go out and scan all species. It’s what’s called a day-one competency. The day they qualify, they’re supposed to be able to do an abdominal scan.”

Before phantom dog Lillie entered the picture, these kinds of courses required attendees to bring their own pets to scan. Predictably, this didn’t always go smoothly. “We always bring at least one of our own dogs to the course but you might have 12 dogs running around going crazy, or 12 very grumpy dogs that don’t want to be scanned, and they get tired of lying there and being prodded and poked,” Julie explains. “So we started to talk about a phantom.”

Lillie’s life began ‘on the back of a cigarette packet’ at the London Vet Show. Julie and Angie were speaking to a man who made bladder phantoms for vets to practice cystocentesis, and began drawing diagrammes of what a phantom dog torso would need to be – namely, ultrasound friendly.

Named after Angie’s pet dachshund, Lillie, phantom Lillie went through many prototypes (and three years of trials and tribulations) before it was introduced into Julie and Angie’s teaching. “Lillie isn’t meant to replace training on real animals, but it helps the vets get used to ‘driving the ultrasound machine’ and to work on their hand-eye brain coordination; sliding rocking, rotating the probe and seeing what happens to the image,” Julie continues. “They could then take that skill once they’d fine-tuned it and use it on real patients.”

Going worldwide

Angie and Julie have spoken at numerous UK veterinary conferences, as well as in Portugal and Sweden, and in September they will head to Sitges in Spain to deliver presentations. And now... there is Lillie.

In the three years since her inception, Lillie has led an interesting life. Soft launched at the London Vet Show in November 2024, the phantom attracted much attention. “Although we’ve done this for ourselves, one company came up to us – an ultrasound equipment manufacturer – and said: ‘We need to buy one. Can we buy one today? Because we want it on our stand,’” Julie tells Synergy. “And we thought: ‘This might have legs.’

“Although Lillie has no legs. No head, no tail, no legs.”

Aspire UCS course attendees have signed up for training from all over the world, from Lebanon and the UAE to the US and Australia. One American sonographer took such a liking to Lillie that Julie and Angie left the phantom with her – and the sonographer promptly took Lillie to the Las Vegas Veterinary Conference in Nevada, where she was a massive hit. In fact, Lillie has proved so popular in the US that Julie and Angie have been invited to the British Embassy in New York in August to show her off.

Going worldwide

Angie and Julie have spoken at numerous UK veterinary conferences, as well as in Portugal and Sweden, and in September they will head to Sitges in Spain to deliver presentations. And now... there is Lillie.

In the three years since her inception, Lillie has led an interesting life. Soft launched at the London Vet Show in November 2024, the phantom attracted much attention. “Although we’ve done this for ourselves, one company came up to us – an ultrasound equipment manufacturer – and said: ‘We need to buy one. Can we buy one today? Because we want it on our stand,’” Julie tells Synergy. “And we thought: ‘This might have legs.’

“Although Lillie has no legs. No head, no tail, no legs.”

Aspire UCS course attendees have signed up for training from all over the world, from Lebanon and the UAE to the US and Australia. One American sonographer took such a liking to Lillie that Julie and Angie left the phantom with her – and the sonographer promptly took Lillie to the Las Vegas Veterinary Conference in Nevada, where she was a massive hit. In fact, Lillie has proved so popular in the US that Julie and Angie have been invited to the British Embassy in New York in August to show her off.

What can radiographers learn from Julie’s career?

It’s undeniable that Julie has had a unique career journey so far. With so much under her belt, what’s her advice to other radiographers who might want to follow in her footsteps? “Grow a thick skin, because you will be told you cannot do this,” she begins, followed by: “Question everything. You’ll never understand how things work and the way things are if you don’t question it, because you need to understand it in your own mind.

“Play to your strengths and do something because you love it, not just for the money.”

Next – a crucial part of developing as a radiographer, and as a person – learn from your mistakes but don’t let them define you, she says. “There were so many things I didn’t understand when I set up my first company, Ultrasound Now,” Julie continues. “When I was working out the costs for doing scans, I didn’t factor any wages in for me.

“With my very first contract, which was obviously the most exciting thing I’d ever done in my life, by the time I’d paid the loan for the equipment and everything, I didn’t have enough to pay myself a salary.”

Ultimately, putting your dreams into action might not always work out the way you want, but both successes and failures result in experience, she concludes. “Although I’ve not had what you might call a normal pathway in radiography and I have made mistakes, particularly when I trusted people who betrayed that trust, I’ve had some great adventures and ultimately I can sleep at night knowing that hard work and integrity win in the end.

“Would I choose radiography as a career in my next life? Yes I would –no question.”

More about veterinary ultrasound

The Society of Radiographers offers a number of resources available for those interested in pursuing a career in veterinary ultrasound. Here, you can view a webinar covering ICRP Publication 153: Radiological Protection in Veterinary Practice, a veterinary X-ray risk assessment from the Society of Radiological Protection and a report on Radiation Protection and Safety in Veterinary Medicine from the International Atomic Energy Agency.

For more information on ultrasound generally, check out SoR resources here or look into the Ultrasound Advisory Group SIG here.

Read more