From digs to diagnostics: how Jennifer Wood went from archaeologist to radiographer

Transitioning from one career to another doesn’t have to be dramatic or scary. Jennifer tells Synergy why she chose to make the move, and how she feels about her new profession

Jennifer Wood

Jennifer Wood

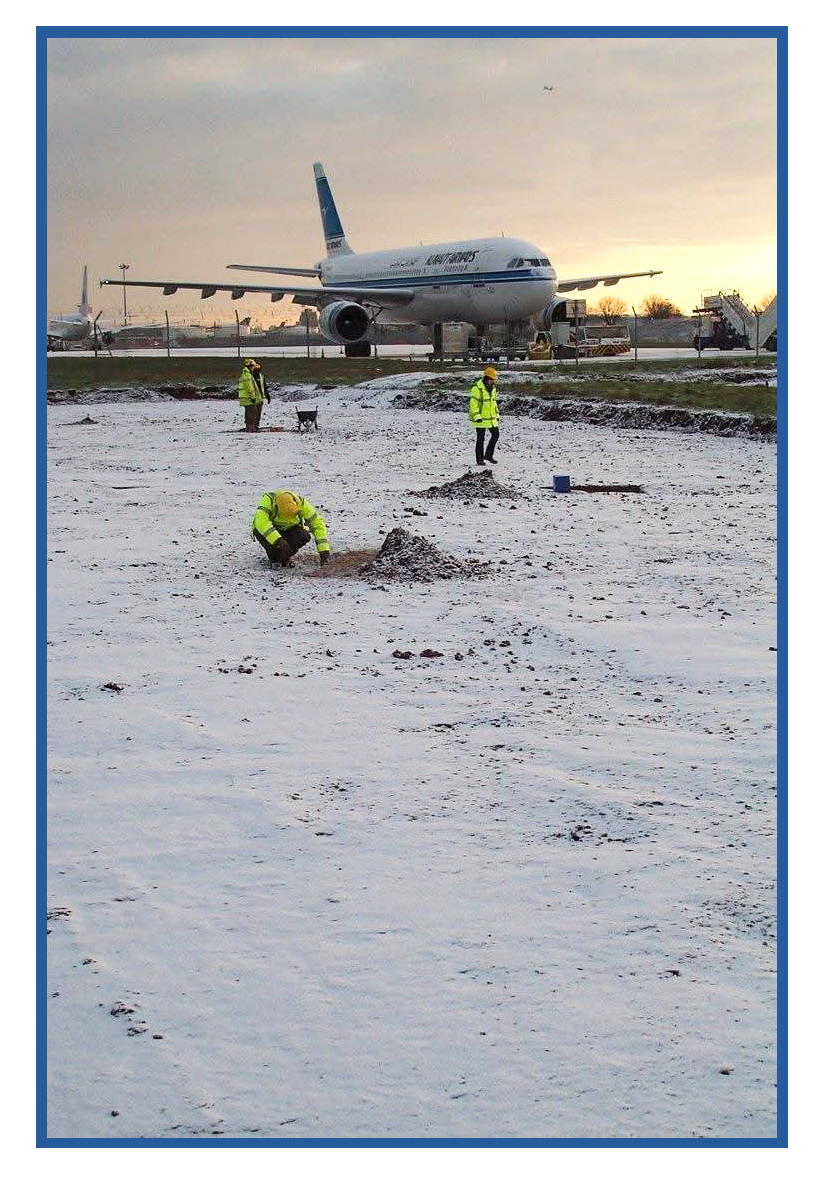

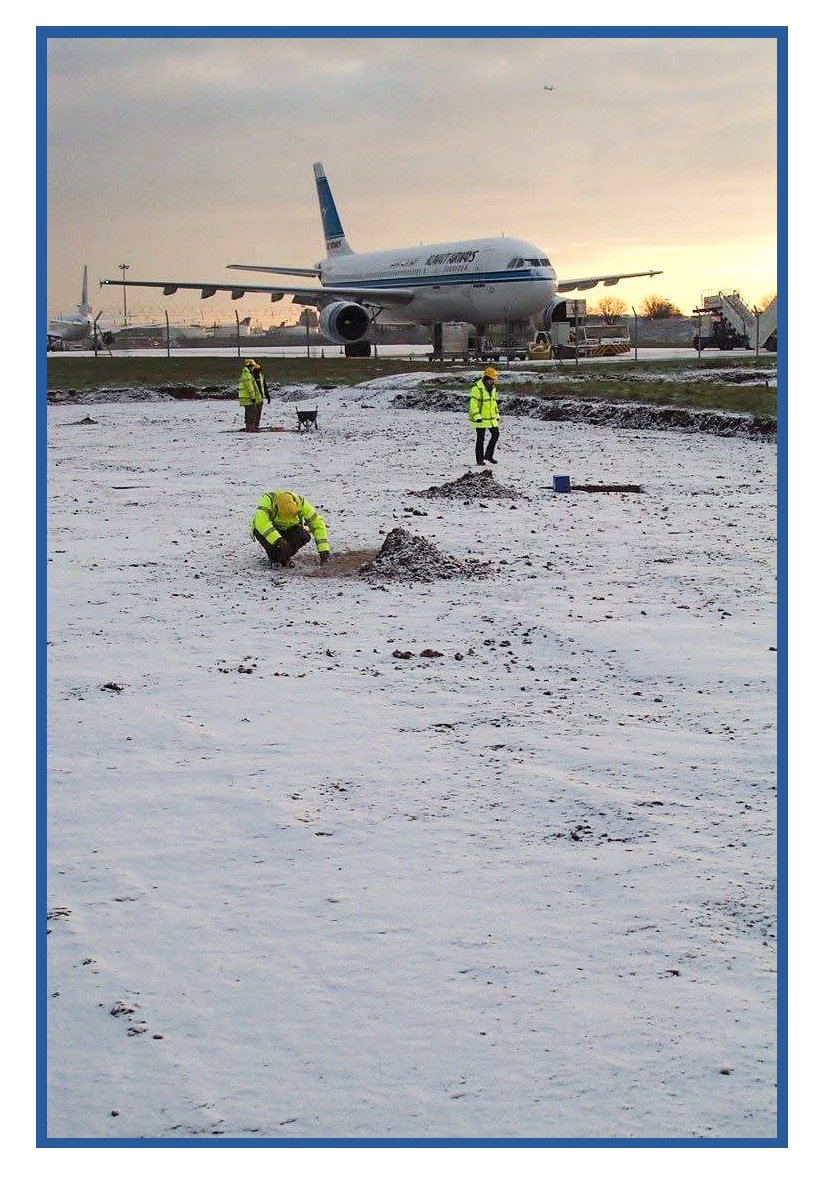

Jennifer Wood has spent a lifetime studying skeletons – but not always as a radiographer. After an almost 20-year career studying human skeletal remains in an archaeological context, she felt something was missing. Swapping the bones of the dead for the bones of the living, Jennifer began training and working as a radiographer, bringing with her a wealth of experience studying the human skeleton.

Synergy finds out why she made the change, and how she compares investigating bones from hundreds of years ago to those of today.

Great to meet you Jennifer – could you introduce yourself?

I am an advanced practitioner in plain film reporting. I work at United Lincolnshire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and I’ve been a radiographer for about nine years now. Before that I was an osteoarchaeologist, so I’ve had a bit of a transition.

What prompted your career transition after doing archaeology for so long?

My home situation changed. I got married, had children and found the transient lifestyle involved in being an archeologist was not quite conducive to raising a family. But ultimately, it came down to the fact that I was getting a bit bored. The work has always been a little intermittent, because no one ever knows what they’re going to find. Also, osteoarcheology is quite lonely work, because it’s basically you and the person you’re dealing with – who’s not very talkative at the best of times!

I realised that I was ready for something new, and I knew I had this body of experience with skeletal systems and anatomy, but I fancied working with living people for a change. I really liked the idea of doing something that would make a difference and would be helpful. Not that I don’t feel that archaeology makes a difference, but I don’t think it has the level of importance that, say, helping someone on their healthcare journey has. I also feel I’m giving to the community a bit more.

But why radiography specifically? What attracted you to the profession?

I chose radiography over all the other things I could have gone for because I had many years of experience working with skeletal remains that I didn’t want to lose. I was also looking for something that I felt I could apply that level of knowledge to but, as I say, in a more supportive and helpful environment, which I felt would benefit the community and other people better.

I just had one of those epiphany moments of: ‘Oh, what are those people called who take the X-rays?’ I contacted my local hospital, which happens to be where I work now, and they welcomed me in. They gave me an insight into the department. They allowed me to come and observe how they worked. And after that, I think it was 12 hours after I finished my placement, I decided that was the place for me, and I put in my application to do my undergraduate degree in radiography.

Were there any transferable skills from osteoarchaeology?

There’s a lot less mud! As an archaeologist, I think you learn to be adaptable, because you never know what’s going to be thrown at you. You never know what you’re going to find, or if you’re even going to find anything. You’re always working in a different place, with different people, often in a different area of the country. That adaptability has been really useful for becoming a radiographer, because you never know who you’re going to get through the door or what you’re going to be dealing with. That resilience has been very beneficial.

Being able to work across multidisciplinary teams helps too. In archaeology we all have our own specialisms; we all have our own drives and goals of what we’re hoping to achieve, from research to assemblage. From an archaeology point of view, it’s bringing all those specialisms together and trying to come up with this holistic approach – trying to get the full picture. This experience has been really useful for understanding how to work with other people in the medical profession. When you’re dealing with people who are obviously passionate about their own specialisms, about their own agendas, needs and wants and research, being able to understand helps to pull it all together.

Whether you’ve got some working hypotheses or are working towards the benefit of the patient, I think those are really great, transferable skills.

How have you found radiography during your time in the profession?

The thing I love about radiography is that no day is the same. And radiographers are a great group of people. They’re really adaptable, friendly and welcoming, so it’s a great team to be in. And then we’ve got this element of unexpectedness when our patients come through the door, and it involves a lot of problem-solving skills.

It has that level of challenge and excitement that never seems to wane. I’ve had to do an awful lot of additional education to get this far. So it’s quite challenging in that respect, to have to do all that learning and try to change my mindset from quite a static, academic approach to something that is really dynamic and changing all the time, especially with the changes in technology, which is exciting and fast paced.

With archaeology, you’re talking about things that have been there for thousands and thousands of years. A lot of thought and a lot of study won’t change the field as dramatically or as quickly as radiography, where technology and new research can change everything within a five-year period.

That takes a little bit of time, mentally, to get your head around. Some days it can be quite a grind. You have to put yourself out there a lot more, emotionally speaking, when you’re working in the NHS. And it can be hard work, but it’s very rewarding.

You’re currently working as a reporting radiographer – is that a role you want to stay in? Or are there other fields you’re interested in getting involved with?

At the moment I’m happy where I am – I still find it a very dynamic and interesting area, and I think we’re still always learning. There’s always something new; always a new case that we’ve never come across. Saying that, I have just started as an associate lecturer at the University of Lincoln for the new diagnostic radiography course! So I’m helping support them there.

Within my role as a reporting radiographer, I am spreading my tendrils a little bit. I’m heavily involved with our student teaching package within our hospital, and I’ve got my fingers in here, there and everywhere within the department. I’m also a Society of Radiographers’ representative.

What advice would you give to anyone who’s interested in making that kind of career transition or getting involved with radiography more generally?

Get some experience. Go and visit a department and look at what radiography actually is. It’s an amazingly diverse career that offers an awful lot of variety, and it’s really rewarding. You’ve got to love it. If you love it, it’s one of the best careers out there.

Jennifer Wood

Jennifer Wood

Jennifer Wood has spent a lifetime studying skeletons – but not always as a radiographer. After an almost 20-year career studying human skeletal remains in an archaeological context, she felt something was missing. Swapping the bones of the dead for the bones of the living, Jennifer began training and working as a radiographer, bringing with her a wealth of experience studying the human skeleton.

Synergy finds out why she made the change, and how she compares investigating bones from hundreds of years ago to those of today.

Great to meet you Jennifer – could you introduce yourself?

I am an advanced practitioner in plain film reporting. I work at United Lincolnshire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and I’ve been a radiographer for about nine years now. Before that I was an osteoarchaeologist, so I’ve had a bit of a transition.

What prompted your career transition after doing archaeology for so long?

My home situation changed. I got married, had children and found the transient lifestyle involved in being an archeologist was not quite conducive to raising a family. But ultimately, it came down to the fact that I was getting a bit bored. The work has always been a little intermittent, because no one ever knows what they’re going to find. Also, osteoarcheology is quite lonely work, because it’s basically you and the person you’re dealing with – who’s not very talkative at the best of times!

I realised that I was ready for something new, and I knew I had this body of experience with skeletal systems and anatomy, but I fancied working with living people for a change. I really liked the idea of doing something that would make a difference and would be helpful. Not that I don’t feel that archaeology makes a difference, but I don’t think it has the level of importance that, say, helping someone on their healthcare journey has. I also feel I’m giving to the community a bit more.

But why radiography specifically? What attracted you to the profession?

I chose radiography over all the other things I could have gone for because I had many years of experience working with skeletal remains that I didn’t want to lose. I was also looking for something that I felt I could apply that level of knowledge to but, as I say, in a more supportive and helpful environment, which I felt would benefit the community and other people better.

I just had one of those epiphany moments of: ‘Oh, what are those people called who take the X-rays?’ I contacted my local hospital, which happens to be where I work now, and they welcomed me in. They gave me an insight into the department. They allowed me to come and observe how they worked. And after that, I think it was 12 hours after I finished my placement, I decided that was the place for me, and I put in my application to do my undergraduate degree in radiography.

Were there any transferable skills from osteoarchaeology?

There’s a lot less mud! As an archaeologist, I think you learn to be adaptable, because you never know what’s going to be thrown at you. You never know what you’re going to find, or if you’re even going to find anything. You’re always working in a different place, with different people, often in a different area of the country. That adaptability has been really useful for becoming a radiographer, because you never know who you’re going to get through the door or what you’re going to be dealing with. That resilience has been very beneficial.

Being able to work across multidisciplinary teams helps too. In archaeology we all have our own specialisms; we all have our own drives and goals of what we’re hoping to achieve, from research to assemblage. From an archaeology point of view, it’s bringing all those specialisms together and trying to come up with this holistic approach – trying to get the full picture. This experience has been really useful for understanding how to work with other people in the medical profession. When you’re dealing with people who are obviously passionate about their own specialisms, about their own agendas, needs and wants and research, being able to understand helps to pull it all together.

Whether you’ve got some working hypotheses or are working towards the benefit of the patient, I think those are really great, transferable skills.

How have you found radiography during your time in the profession?

The thing I love about radiography is that no day is the same. And radiographers are a great group of people. They’re really adaptable, friendly and welcoming, so it’s a great team to be in. And then we’ve got this element of unexpectedness when our patients come through the door, and it involves a lot of problem-solving skills.

It has that level of challenge and excitement that never seems to wane. I’ve had to do an awful lot of additional education to get this far. So it’s quite challenging in that respect, to have to do all that learning and try to change my mindset from quite a static, academic approach to something that is really dynamic and changing all the time, especially with the changes in technology, which is exciting and fast paced.

With archaeology, you’re talking about things that have been there for thousands and thousands of years. A lot of thought and a lot of study won’t change the field as dramatically or as quickly as radiography, where technology and new research can change everything within a five-year period.

That takes a little bit of time, mentally, to get your head around. Some days it can be quite a grind. You have to put yourself out there a lot more, emotionally speaking, when you’re working in the NHS. And it can be hard work, but it’s very rewarding.

You’re currently working as a reporting radiographer – is that a role you want to stay in? Or are there other fields you’re interested in getting involved with?

At the moment I’m happy where I am – I still find it a very dynamic and interesting area, and I think we’re still always learning. There’s always something new; always a new case that we’ve never come across. Saying that, I have just started as an associate lecturer at the University of Lincoln for the new diagnostic radiography course! So I’m helping support them there.

Within my role as a reporting radiographer, I am spreading my tendrils a little bit. I’m heavily involved with our student teaching package within our hospital, and I’ve got my fingers in here, there and everywhere within the department. I’m also a Society of Radiographers’ representative.

What advice would you give to anyone who’s interested in making that kind of career transition or getting involved with radiography more generally?

Get some experience. Go and visit a department and look at what radiography actually is. It’s an amazingly diverse career that offers an awful lot of variety, and it’s really rewarding. You’ve got to love it. If you love it, it’s one of the best careers out there.

Find out more about careers in radiography

The College of Radiographers (CoR) Education and Career Framework (ECF) (fourth edition) provides guidance for the education and career development of the radiography profession. The goal of the ECF is to support improved outcomes for patients through the education and development of the radiography workforce.

To find out more about the ECF, and how it informs the accreditation of individual members of the radiography workforce, click here.

Read more