Professional

From cradle to grave

Dr Claire Robinson MBE, consultant radiographer in post-mortem imaging, reflects on a career which ranges from disaster victim identification to scanning King Richard III

Claire Robinson MBE

Claire Robinson MBE

I became a radiographer in 2001 and, like most other radiographers, just wanted to help patients have a better experience through their ill health.

I started as a general radiographer at University Hospitals Leicester and after a couple of years specialised in trauma. I really enjoyed the unpredictability of working in A&E, and the challenge of adapting techniques to get beautiful X-rays when the patient is unable to move.

I also liked working out of hours but I know some colleagues dreaded working with me because I was “that radiographer” who had the busiest nights and it wasn’t unusual for something to go awry when I was around, like having to catch a bat flying around the X-ray department at 3am.

Working nights also gave me time to do an MSc. At the time, we did three long nights so I had the rest of the week off to study. I did a self-funded distance learning MSc which was a challenge as it was mainly self-directed learning, though I picked up some skills which came in useful when taking on a PhD – determination and a degree of stubbornness.

In 2008 I was promoted to a senior trauma radiographer and in January 2009 to an advanced practitioner post in post-mortem (PM) imaging. It was a new post, the first in the UK, so I had to develop the role. At the start I was still working half the week clinically but as the PM services developed, this reduced and I stopped working clinically when I started my PhD in 2014.

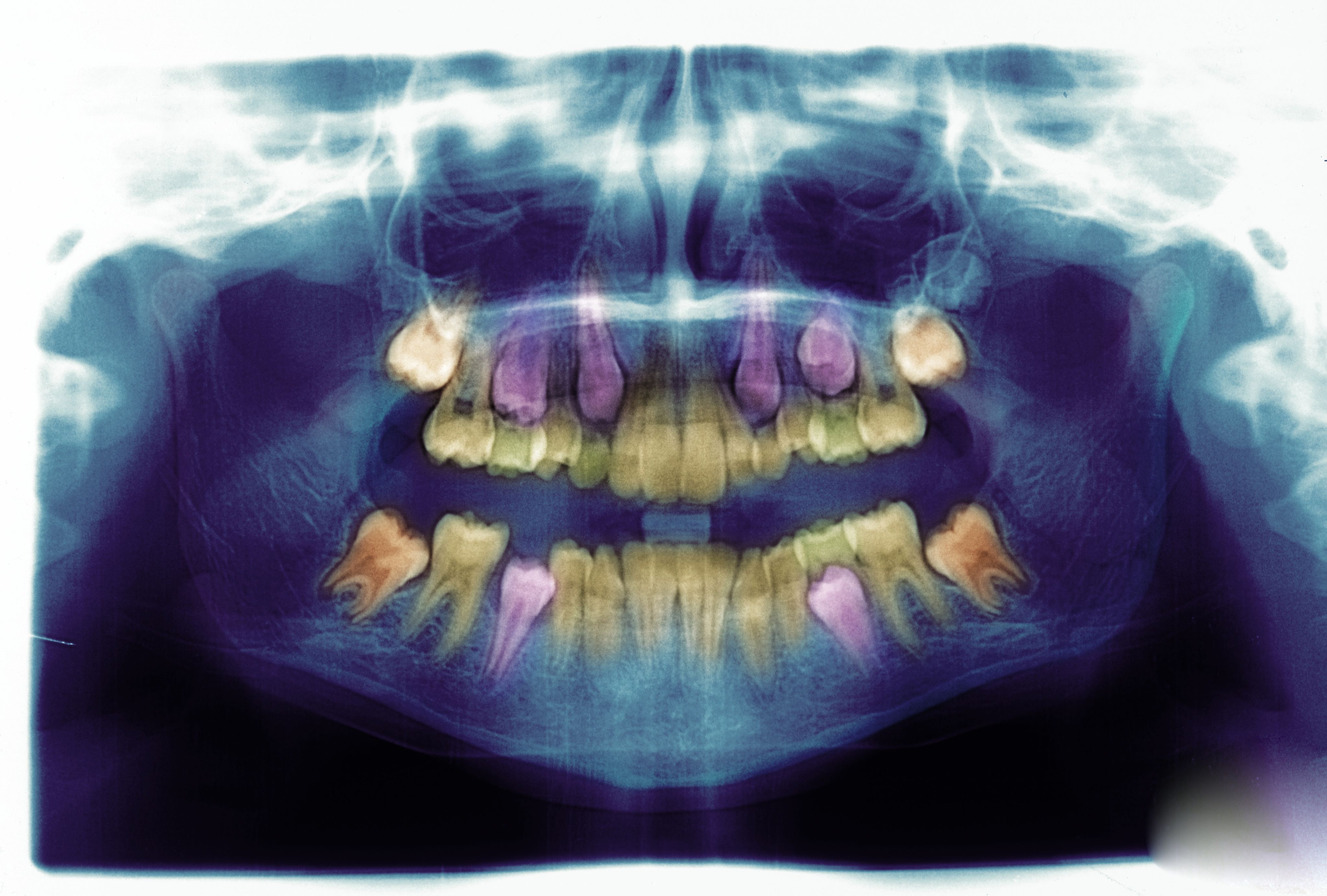

I studied non-suspicious deaths, particularly diagnosing coronary artery disease. In England and Wales we investigate more non-suspicious deaths than most other countries and so we aimed to replace most invasive autopsies with PMCT scanning. I was awarded a National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) clinical doctoral research fellowship. I was only the second radiographer to receive one and without it I would not have been able to do my PhD. I was delighted when I was awarded my PhD in June 2021 and am very grateful to all that helped me, particularly my main supervisor Professor Bruno Morgan.

In December 2021 I was promoted to Consultant Radiographer in PM imaging. I still run the PM imaging services, although that will be changing soon so I can concentrate on developing the PM imaging services, doing some more research that I want to do and helping others set up PM imaging services. I’m helping more than ten hospitals and organisations at the moment. I’m not saying we are the best but in Leicester we have had a lot of experience, which we share, particularly our mistakes, to save others time.

Forensic imaging

I became involved in forensic imaging shortly after starting at Leicester. I had not heard of it before but when someone asked if I wanted to go to the mortuary to do a couple of X-rays, I agreed. I hadn’t anticipated the other radiographer being a little reluctant at the last minute so I did them. It was like any other imaging - they were still a patient.

A year or so later, I attended a conference which got me involved in what was to become the International Association of Forensic Radiographers (IAFR) and I’m still a member of the international committee and Chair of the UK branch. I also chatted with Professor Guy Rutty, a Leicester pathologist who I had worked with a few times. I met him on the stairs at work a few weeks later and he asked if I was interested in getting involved in some research. I was and did, and it started my career in forensic imaging.

Forensic radiography is most often the use of imaging to help determine who someone is and how they died. They are legal investigations in which someone may have purposefully or accidentally caused a death. But there is a lot more to forensic imaging. “Forensic” means to do with the courts and law, so it also includes live investigations such as assault, suspected physical abuse or drug smuggling (body packing).

There are also deceased imaging cases that are called “forensic” but are not part of a legal investigation so I also use the term “post-mortem imaging" to describe what I do. This might be imaging at the request of a family to help understand why someone has died, or some deaths referred by a Coroner, or archaeological imaging, including when I scanned “the king in the car park”, Richard III.

"And yes, I do still refer to the deceased as patients - the NHS is 'from cradle to grave', not cradle to death."

Post-mortem (PM) imaging

Since I started in 2001, our PM imaging services have developed hugely. We are the only hospital I can find that has a forensic unit, paediatric pathologist and non-suspicious death service on one site. We are unique to be able to provide the whole range of forensic and PM imaging.

Some of the imaging at Leicester has replaced the need for an invasive autopsy for adult trauma deaths and adult non-suspicious deaths (the majority of our work) and as an adjunct to an autopsy in forensic cases and all paediatric deaths.

As the services develop, I am determined to maintain the high standards we have set for ourselves. This includes treating each deceased with dignity and respect. We are looking after these individuals when they are at their most vulnerable, and ensuring that they receive the same level of care and respect as any other patient is very important to me. And yes, I do still refer to the deceased as patients - the NHS is “from cradle to grave”, not to cradle to death.

Disaster Victim Identification

I started off in research as a Band 5 radiographer. It was not part of my job and was not paid to begin with but was very interesting and I got my name on a few papers, which was exciting, and provided me with a project for my MSc dissertation.

It also took me to the Home Office in London to advise on the use of CT in forensic and particularly mass fatality incidents. I remember sitting in one meeting thinking what on earth was I, a Band 5 radiographer, doing among such senior people but it enabled me to become involved in one of the most interesting and rewarding parts of my job – Disaster Victim Identification (DVI).

DVI is an internationally accepted process for recovering and identifying those killed in major incidents. DVI is not really part of my NHS role - dealing with those killed as a result of incidents is not an NHS responsibility - but I am very fortunate that my managers see it as important and allow me time away from work if it's needed.

Forensic imaging is not for everyone and DVI is the same, but more so, because it's in response to an event that has caused devastation, both in physical and environmental terms and, more importantly, in emotional terms for those who have lost loved ones so suddenly and in very difficult circumstances. There will also be interest from the media, politicians and families and communities, so it can be pressured.

I’ve been involved in DVI for most of my career and have assisted in major incidents such as the Malaysia Airlines MH17 plane crash, Manchester Arena bombing and Grenfell Tower fire. Due to my experience, I get involved at the beginning of a response and help set up and then work in the imaging service. I usually get a phone call asking me to attend a meeting wherever the DVI mortuary is being set up.

Looking back

I’ve learnt that laughter is an essential part of life and work, but never at the expense of the deceased. Working with them, you see stories and physical evidence of illness and accidents and sometimes it can be tough. There are a few cases I will never forget but, rather than upsetting me, I find the work rewarding.

Knowing I have helped a family find out why their loved one has passed away, or helped identify a person so they can be returned to their loved ones, and in many cases in Leicester without the need for an invasive autopsy, is a privilege.

And when you’re offered an interesting opportunity, take it, even if it means putting yourself out a little. You never know where it will lead. For me, to a Phd and MBE - I certainly didn’t expect those when I started my career.

An unusual encounter

King Richard III

King Richard III

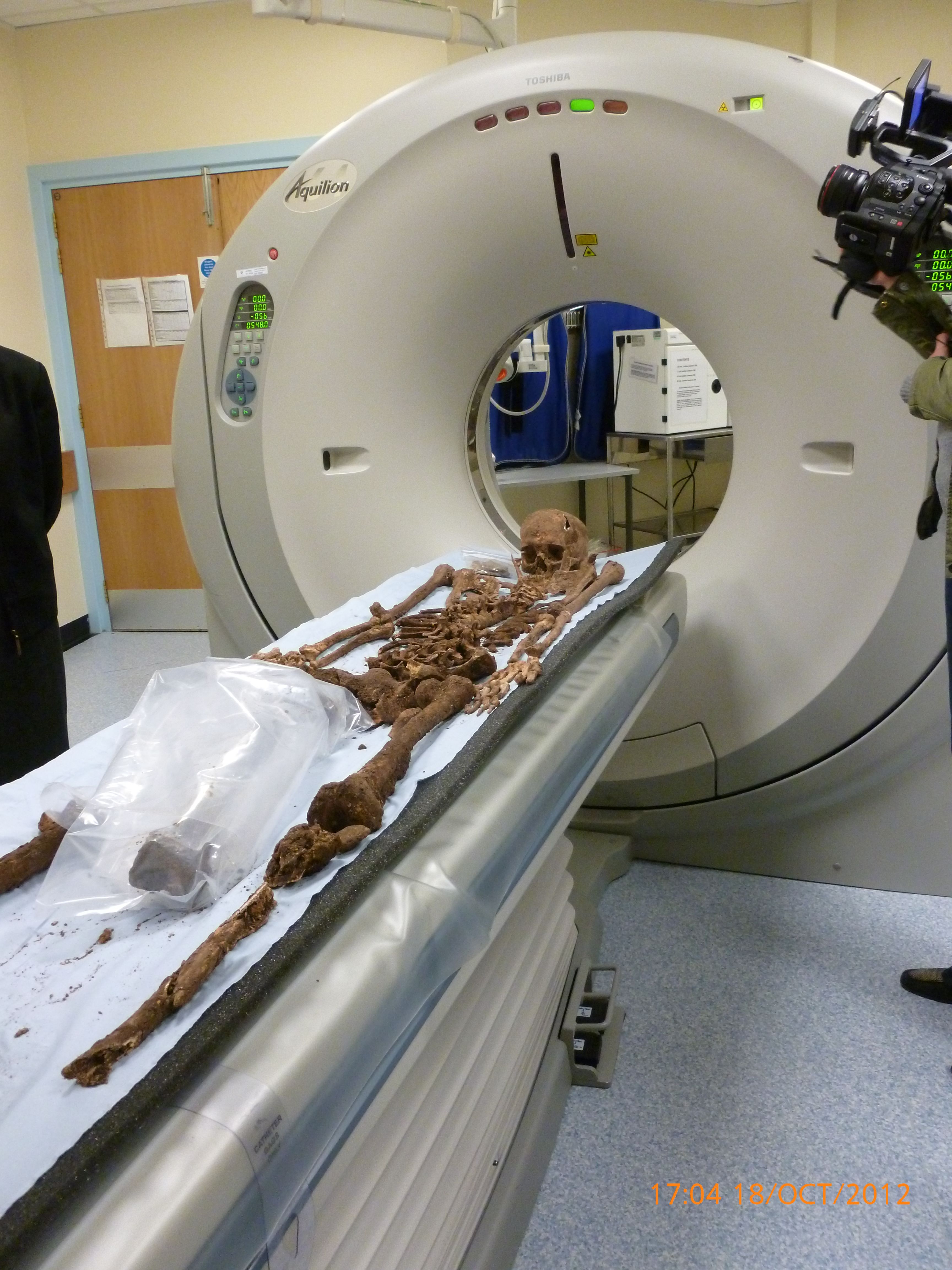

The king's remains being scanned

The king's remains being scanned

The scanning of Richard III

Claire reflects on the operation that changed history

I was possibly the least appropriate person to scan King Richard III. I have never had much interest in history but I was very interested in the science behind it. So, when in 2012 Professor Bruno Morgan and I were approached to see if we could scan any remains found in the car park, we agreed. I had not appreciated that it was to be filmed (very unlikely to happen again!) and that it had to be done in secret. Secrecy in an NHS hospital with a film crew involved?

The bones were delivered to the scanner in boxes by the archaeological team. Dr Jo Appleby, an archaeologist from the University of Leicester, was a joy to work with and very open about what they had been doing and how they had found the remains. It was only the second time the bones had been laid out since being dug up and they were still very wet and fragile – one actually broke on the scanner.

I had reservations about scanning the remains laid out anatomically (although it did make for a great photo) and suggested each bone may be better scanned individually but they wanted them scanned as they were, so we scanned. The bones returned a few weeks later, following further discussion, for each bone to be scanned individually. This time the bones had been dried, so establishing the best protocol for scanning was interesting.

The scans were used for the 3D printing of King Richard’s spine to determine the degree of scoliosis, for the skeleton to go on show at the Richard III Visitor Centre in Leicester and in the 3D reconstruction of the head shown at the announcement of his identification.

Case studies: Forensive radiography

Laura Knight

Teaching Fellow, Diagnostic Radiography and Medical Imaging,

University of Portsmouth

I first encountered forensic radiography as a student on placement - it fascinated me that we could image patients to assist diagnosis in death, as we do in life. Upon graduating in 2012, I became a specialist paediatric radiographer, where Suspected Physical Abuse (SPA) skeletal surveys were a large part of my normal workload. My first experience of PM imaging came a few months into my job, and have since undertaken many paediatric cases alongside living SPA skeletal surveys.

I have been afforded so many learning opportunities within forensic radiography. In 2019 I started a PgCert, hoping to increase my knowledge of paediatric forensic imaging. However, I was more deeply enthralled learning about the other avenues of forensic radiography, with which I had little previous experience. This spurred me on to undertake my MSc, which I completed in July after conducting a research project centred on paediatric forensic imaging.

In 2018 I joined the IAFR and was a founding committee member of the UK branch, where I serve as the secretary and communications officer. This has allowed me to meet many amazing, knowledgeable radiographers with forensic imaging in common and refine the knowledge I acquired as part of my studies.

Now, in my teaching role, I have the privilege of fostering undergraduate students' interest in forensic imaging, alongside teaching paediatric radiography - both subjects that I love. I have also been lucky enough to present internationally on forensic radiography in paediatrics. I feel privileged to work in this niche, tight-knit and emotive but valuable field of radiography.

Amy-Lee Brookes

Lead Post-Mortem Radiographer,

Royal Preston Hospital,

Lancashire Teaching Hospitals

During my undergraduate studies in 2013, I was fortunate enough to attend a lecture by an experienced forensic radiographer, and that day I decided I wanted to pursue a career as a forensic radiographer. At the time there were no options for a full-time career in forensics in the UK but I was not put off by this!

In my first radiography post, I pursued every forensic opportunity, such as assisting and leading SPA live cases and assisting with PM paediatric cases. In 2014, I started the MSc in Forensic Radiography at Teesside University and joined the IAFR. In 2015, after completing my first year at Teesside and gaining more SPA experience, I joined the IAFR committee and DVI team.

I felt I had reached the limit in my first post and so applied for a job at Great Ormond Street Hospital, which allowed me to gain more experience in paediatric forensic imaging and PM imaging, as well as pursue my MSc research. Living in London also allowed me to undertake volunteer work at the Museum of London and UCL, both with skeletal remains. In 2017, I undertook my first DVI deployment in London and I stepped into the role of DVI Coordinator for IAFR.

For the past five years I have worked as a full-time PM CT lead radiographer in an NHS mortuary CT department. During this time I have stayed working with the IAFR and, recently, the IAFR UK branch, as well as teaching at lectures, universities and conferences and being active in PM research.

Find out more...

Dr Claire Robinson MBE is Consultant Radiographer in PM imaging at University Hospitals Leicester and Chair of the UK branch of the International Association of Forensic Radiographers. For further information visit the IAFR website or email uk@iafr.org.uk.

Claire is also part of a new network of UK radiologists and radiographers interested in post-mortem and forensic imaging, to share ideas and establish good practice. If you are interested in joining the network and completing a short survey, email Claire at PMRadiology@uhl-tr.nhs.uk.

Image credits: Getty Images

University of Leicester

Alex Bartel. Science Photo Library

Now read...