The other side of the fence: a patient experience

Diagnostic Radiographer Kenneth Spencer shares his story after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2022, aged 76

By Kenneth A. Spencer TDCR, MSc.

By Kenneth A. Spencer TDCR, MSc.

Synergy has featured stories by radiographers ‘on the other side of the fence’ following diagnoses requiring treatments and procedures that they have administered to others. In 2022 I found myself in that situation, and thought readers might be interested in my experiences as a patient.

First, an introduction: I joined the Lincolnshire School of Radiography in October 1963. The school provided diagnostic and therapeutic courses; usefully, each group gaining from the other, learning material that crossed their boundaries. In June 1966 I received successful examination results (my age delaying my qualification date by six months) and was ready for my first radiographer post, a locum in Lincoln County Hospital.

I soon moved to London, with its many easily accessible diagnostic imaging departments offering a wide range of experience; teaching being my longer-term ambition. And so I worked in several London hospitals seeking that experience, also spending a short spell working overseas.

By mid-1970 I was attending lectures and courses, preparing for the college’s Higher & Teaching Diploma, and gained a student teacher post at the Royal Free Hospital (Gray’s Inn Road). Simultaneously, I attended a Teaching & Learning course at the Polytechnic of Central London (now Westminster University).

At the end of the 1971 academic year, I was delighted (and somewhat un-believing) to have passed the college’s Higher & Teaching Diploma. I immediately started looking for teaching posts, and in October 1971 I became principal of Bath School of Radiography, based in the Royal United Hospital. At age 25, I was too young for the then Whitley salary scale and age band – my salary was abated by two years!

I spent the next 18 years running the Bath School, also serving as society branch secretary (South West Branch) and as an examiner, later senior examiner, for the College DCR examinations.

In 1988, before gaining an MSc (Medical Computing & Health Informatics) I accepted a key role in the Bath District Health Authority, commissioning and managing a new information system, and training DHA staff in its use. Over several years, I had become involved in health service computing, giving a number of talks all over the country and occasionally abroad. (I also supplied and installed the Society of Radiographers’ very first pair of computers!) Some two years later, I joined the new Wiltshire and Bath Health Commission (soon renamed Wiltshire Health Authority) as assistant director for information. I was to extend the Bath DHA system into the new authority’s constituent organisations: Bath, Swindon and Salisbury DHAs and Wiltshire Family Health Services Authority.

In 1996 I began working part time as a consultant in the Health Authority, after starting a business designing computer software. That soon became my full-time occupation for the next 18 years until retiring aged 68 years.

I had always kept myself fit and well, despite starting life in 1946 with Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA) restricting my early years’ growth and fitness. Just before age five the PDA was ligated (in the new NHS!) One and a half ribs and part of my left lung were removed for posterior access: I still have the 12-inch diagonal scar on the left of the back my chest. (PDA ligation is now less invasive!) Except for that early patient experience (and a right Achilles tendon benign leiomyoma removal at age 40), I had no other significant health issues until age 76, in 2022, when this story really begins.

In June 2016, aged 70, I requested a PSA (prostate specific antigen) test. In 1997, aged 79, my father died of prostatic carcinoma (as did his brother). I knew that some prostate cancers may have genetic links: my youngest brother survived the disease after surgery in his mid-50s, remaining prostate cancer free. My elder sister survived breast cancer, also in her 50s. At the time I was hardly aware of the prostate cancer link with damage to the BRCA genes (brca 1 and brca 2) – ‘brca’ referring to breast cancer, first associated with these genes, later alongside ovarian and prostate cancers.

My PSA was 1.8ng/ml: safe for age 70; I was duly relieved. I planned to retest in 2020 but it slipped my mind and I didn’t have another test until June 2022 at age 76. The result was 9ng/ml, which was suspicious. A retest after six weeks (routine with newly positive results) revealed 10.2ng/ml.

My GP advised urgent referral to the urology team under the two-week wait. The system rapidly swung into action: I attended the urology outpatients clinic and had an MRI scan with gadolinium contrast enhancement. Soon enough I saw the images, and was given the result: I did indeed have prostate cancer, in three centres – the largest about 16mm diameter. At 38cc volume, my prostate was somewhat enlarged: investigation would reveal the nature of the malignancies.

An outpatient appointment was made for a trans-perineal biopsy to determine the nature and extent of my disease. Under local anaesthesia with ultrasound control, biopsy needles passed via my perineum into the prostate, extracting 25 tissue cores, 16 containing adeno-carcinoma.

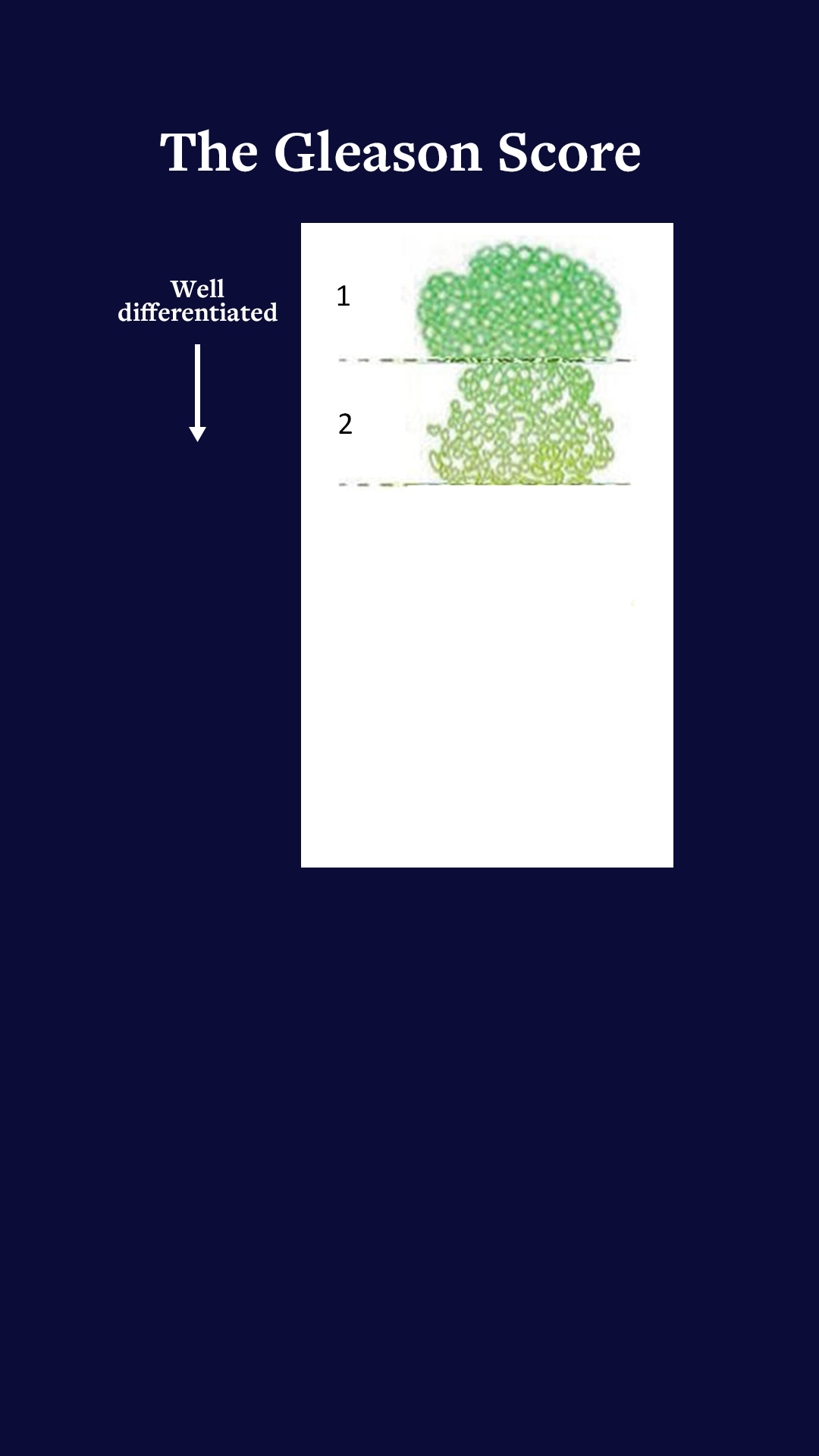

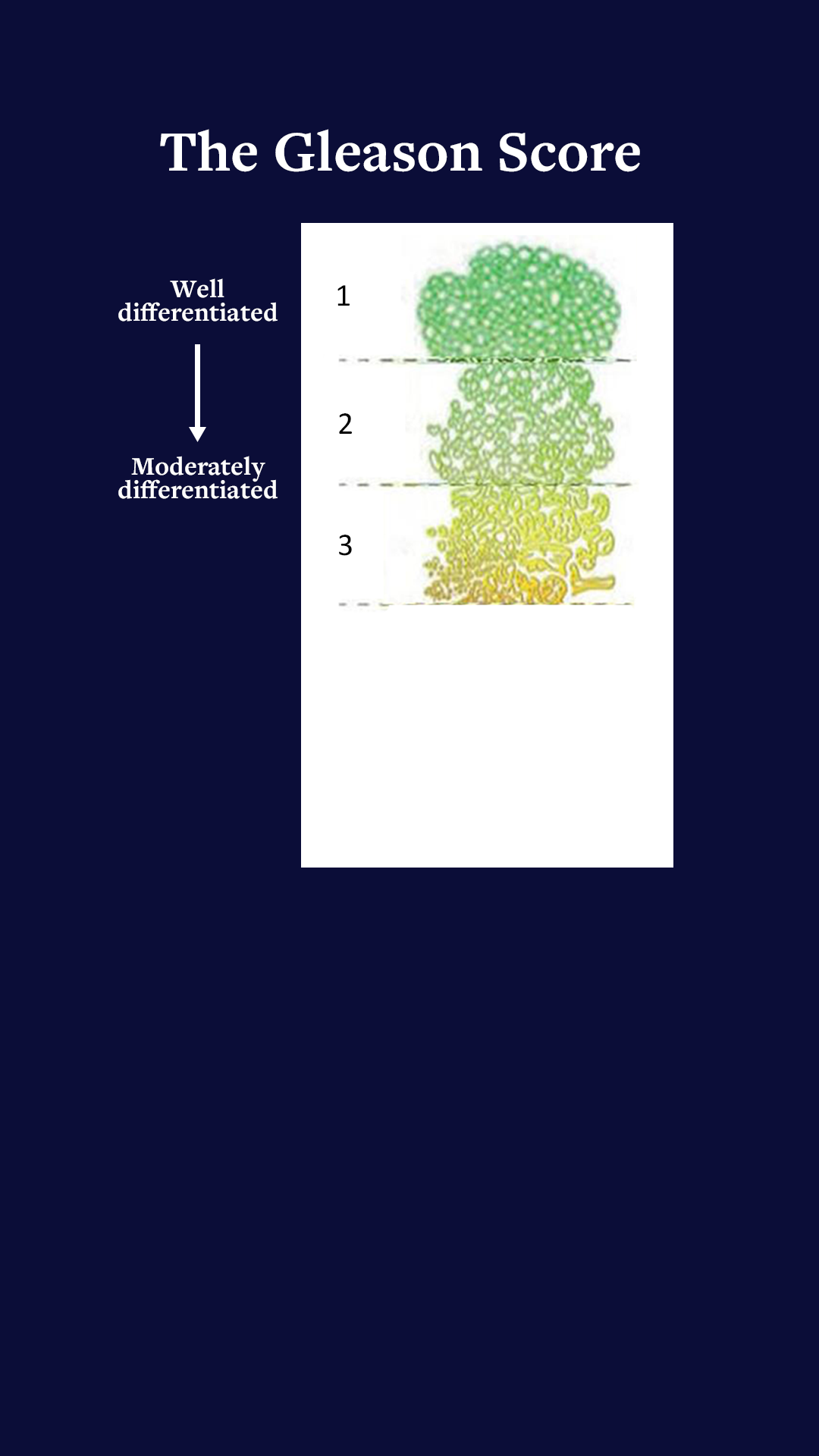

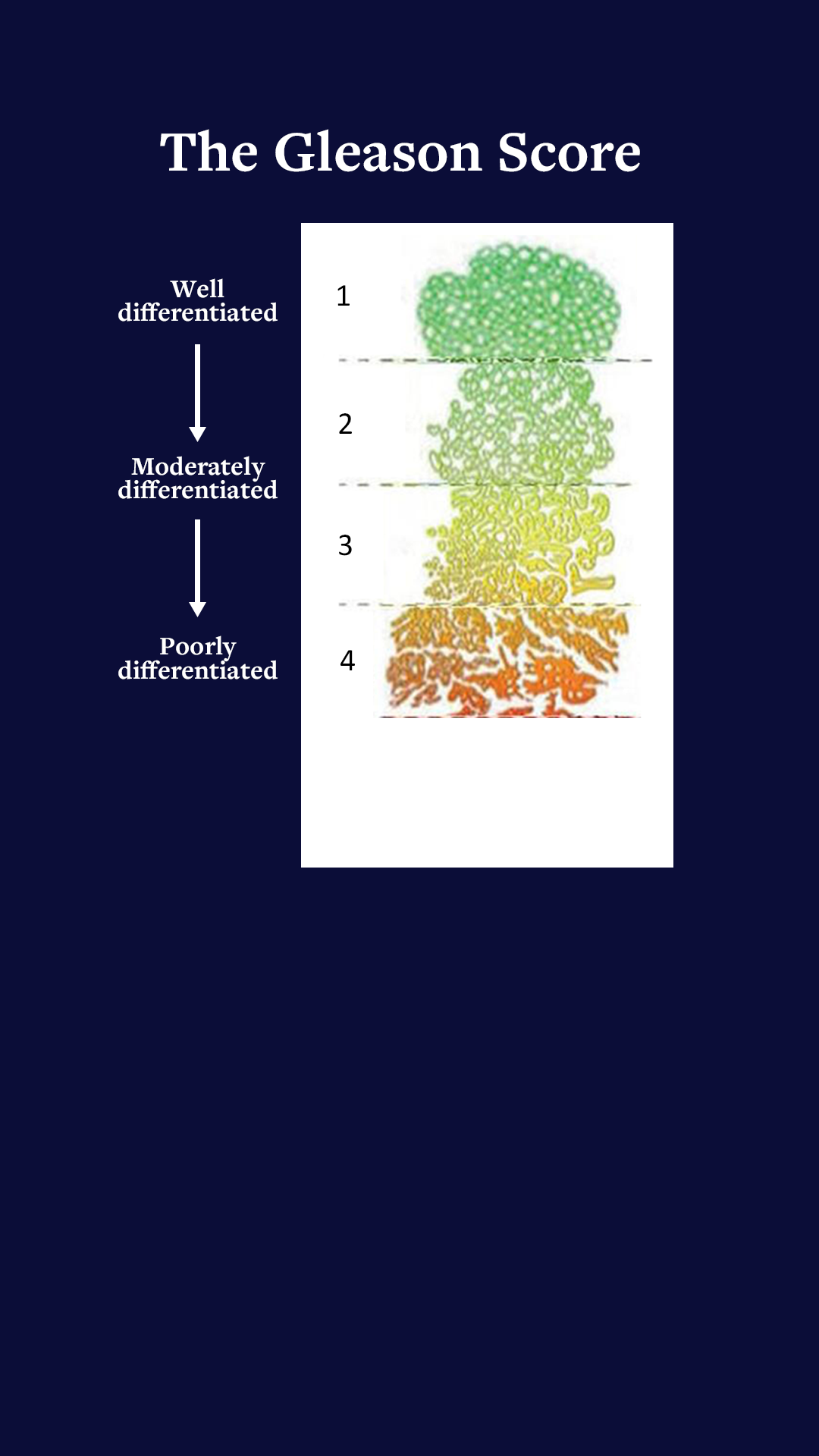

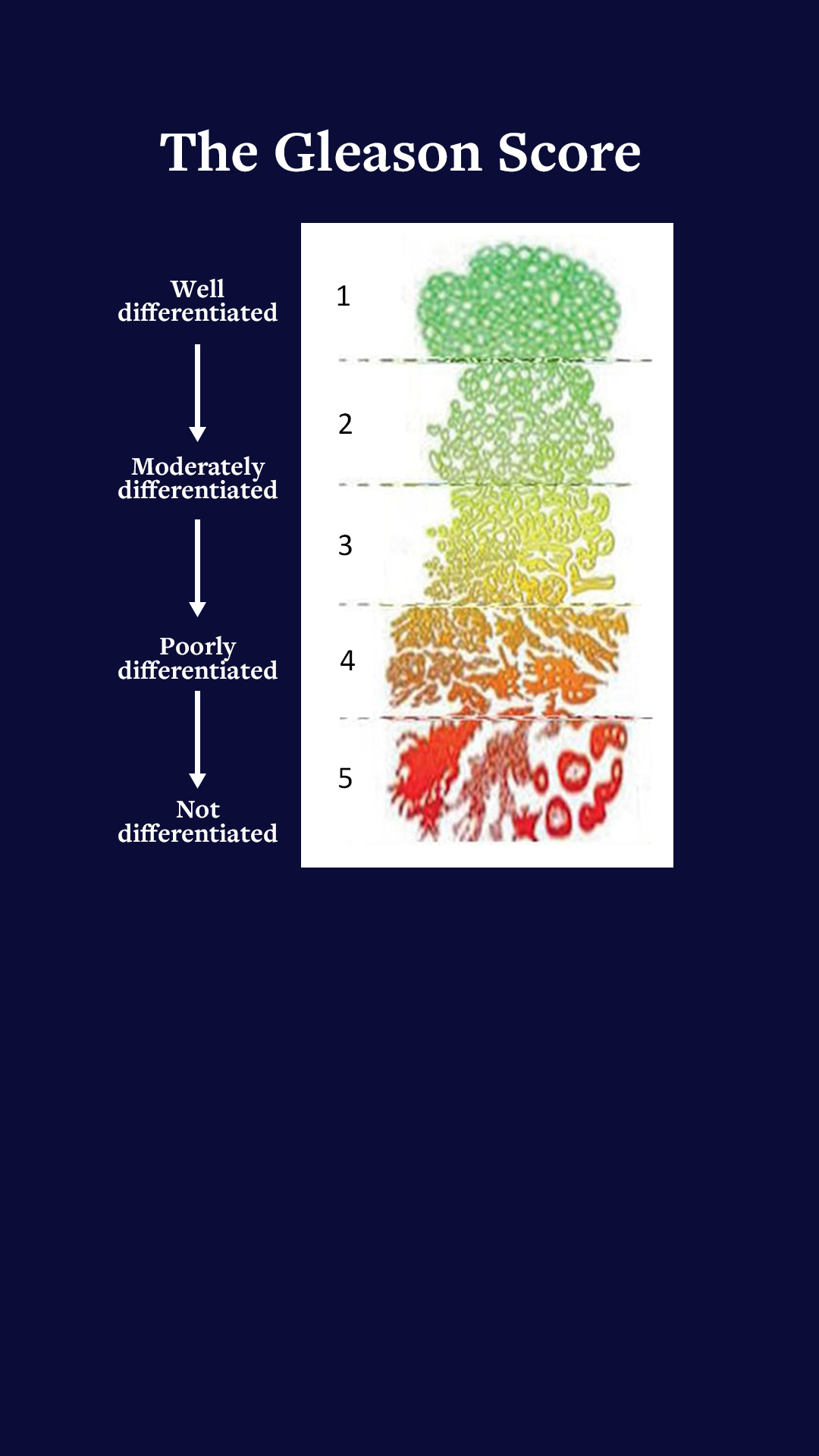

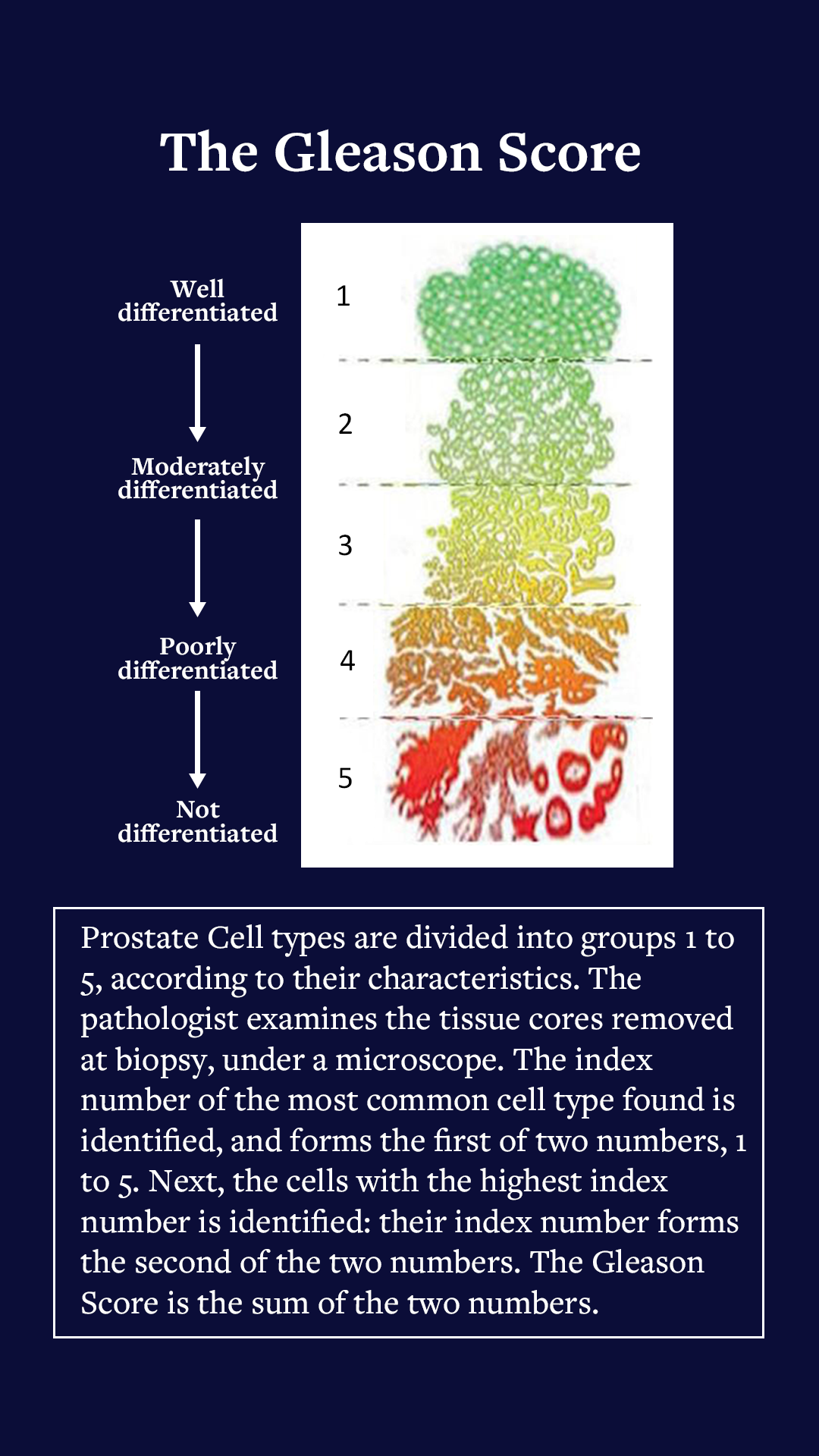

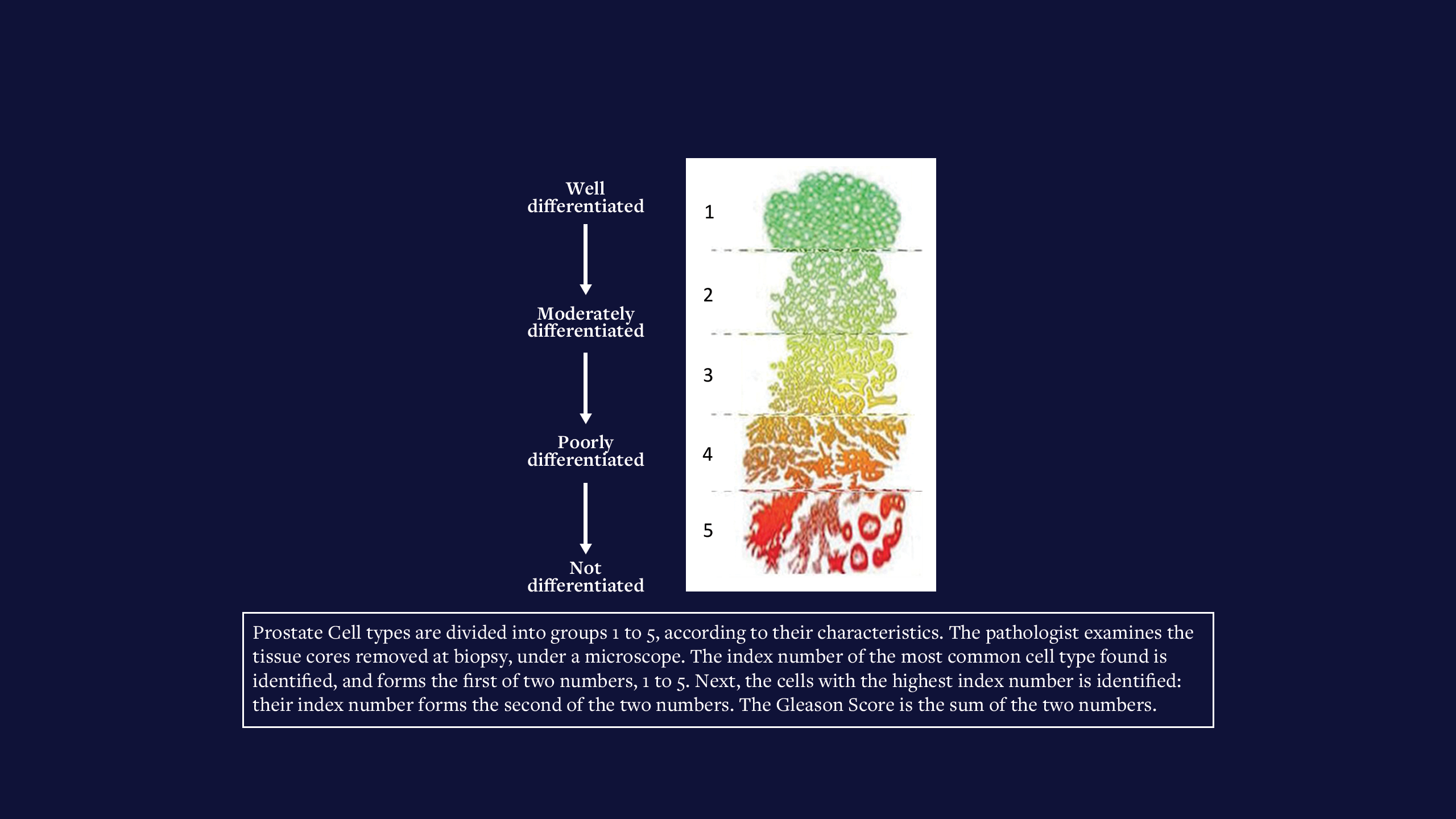

The Gleason Score’s five groups express the degree of disease using outcomes from the pathology testing : Group 1 (normal) to Group 5 (extensive malignancy). The group number of the most common cell type is added to the group number of the most malignant cell type found, to give the Gleason Score. Mine was 3+4=7. Definitely significant but not the worst case.

Having discovered the state of my disease, I must decide on treatment. The online NHS Prostate Predict tool presents current survival and quality of life expectations, against Gleason Score, age, general health and BRCA status, with conservative treatment, versus radical prostatectomy and radical external beam radiotherapy. Short, medium and long-term side effects of the three treatment options may reduce one’s quality of life significantly. (My disease was unsuited to new high-intensity-focused ultrasound, cryogenic and embedded source treatments.)

After much thought, considering Prostate Predict and comparing expectations of survival and side effects, I decided not to have treatment immediately, but to follow the conservative watch-and-wait protocol, (soon amended to active surveillance), with three-monthly PSA checks. At this point, my PSA had been quite stable around 12 -14ng/ml, once actually reducing between a pair of readings.

By Kenneth A. Spencer TDCR, MSc.

By Kenneth A. Spencer TDCR, MSc.

Synergy has featured stories by radiographers ‘on the other side of the fence’ following diagnoses requiring treatments and procedures that they have administered to others. In 2022 I found myself in that situation, and thought readers might be interested in my experiences as a patient.

First, an introduction: I joined the Lincolnshire School of Radiography in October 1963. The school provided diagnostic and therapeutic courses; usefully, each group gaining from the other, learning material that crossed their boundaries. In June 1966 I received successful examination results (my age delaying my qualification date by six months) and was ready for my first radiographer post, a locum in Lincoln County Hospital.

I soon moved to London, with its many easily accessible diagnostic imaging departments offering a wide range of experience; teaching being my longer-term ambition. And so I worked in several London hospitals seeking that experience, also spending a short spell working overseas.

By mid-1970 I was attending lectures and courses, preparing for the college’s Higher & Teaching Diploma, and gained a student teacher post at the Royal Free Hospital (Gray’s Inn Road). Simultaneously, I attended a Teaching & Learning course at the Polytechnic of Central London (now Westminster University).

At the end of the 1971 academic year, I was delighted (and somewhat un-believing) to have passed the college’s Higher & Teaching Diploma. I immediately started looking for teaching posts, and in October 1971 I became principal of Bath School of Radiography, based in the Royal United Hospital. At age 25, I was too young for the then Whitley salary scale and age band – my salary was abated by two years!

I spent the next 18 years running the Bath School, also serving as society branch secretary (South West Branch) and as an examiner, later senior examiner, for the College DCR examinations.

In 1988, before gaining an MSc (Medical Computing & Health Informatics) I accepted a key role in the Bath District Health Authority, commissioning and managing a new information system, and training DHA staff in its use. Over several years, I had become involved in health service computing, giving a number of talks all over the country and occasionally abroad. (I also supplied and installed the Society of Radiographers’ very first pair of computers!) Some two years later, I joined the new Wiltshire and Bath Health Commission (soon renamed Wiltshire Health Authority) as assistant director for information. I was to extend the Bath DHA system into the new authority’s constituent organisations: Bath, Swindon and Salisbury DHAs and Wiltshire Family Health Services Authority.

In 1996 I began working part time as a consultant in the Health Authority, after starting a business designing computer software. That soon became my full-time occupation for the next 18 years until retiring aged 68 years.

I had always kept myself fit and well, despite starting life in 1946 with Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA) restricting my early years’ growth and fitness. Just before age five the PDA was ligated (in the new NHS!) One and a half ribs and part of my left lung were removed for posterior access: I still have the 12-inch diagonal scar on the left of the back my chest. (PDA ligation is now less invasive!) Except for that early patient experience (and a right Achilles tendon benign leiomyoma removal at age 40), I had no other significant health issues until age 76, in 2022, when this story really begins.

In June 2016, aged 70, I requested a PSA (prostate specific antigen) test. In 1997, aged 79, my father died of prostatic carcinoma (as did his brother). I knew that some prostate cancers may have genetic links: my youngest brother survived the disease after surgery in his mid-50s, remaining prostate cancer free. My elder sister survived breast cancer, also in her 50s. At the time I was hardly aware of the prostate cancer link with damage to the BRCA genes (brca 1 and brca 2) – ‘brca’ referring to breast cancer, first associated with these genes, later alongside ovarian and prostate cancers.

My PSA was 1.8ng/ml: safe for age 70; I was duly relieved. I planned to retest in 2020 but it slipped my mind and I didn’t have another test until June 2022 at age 76. The result was 9ng/ml, which was suspicious. A retest after six weeks (routine with newly positive results) revealed 10.2ng/ml.

My GP advised urgent referral to the urology team under the two-week wait. The system rapidly swung into action: I attended the urology outpatients clinic and had an MRI scan with gadolinium contrast enhancement. Soon enough I saw the images, and was given the result: I did indeed have prostate cancer, in three centres – the largest about 16mm diameter. At 38cc volume, my prostate was somewhat enlarged: investigation would reveal the nature of the malignancies.

An outpatient appointment was made for a trans-perineal biopsy to determine the nature and extent of my disease. Under local anaesthesia with ultrasound control, biopsy needles passed via my perineum into the prostate, extracting 25 tissue cores, 16 containing adeno-carcinoma.

The Gleason Score’s five groups express the degree of disease using outcomes from the pathology testing : Group 1 (normal) to Group 5 (extensive malignancy). The group number of the most common cell type is added to the group number of the most malignant cell type found, to give the Gleason Score. Mine was 3+4=7. Definitely significant but not the worst case.

Having discovered the state of my disease, I must decide on treatment. The online NHS Prostate Predict tool presents current survival and quality of life expectations, against Gleason Score, age, general health and BRCA status, with conservative treatment, versus radical prostatectomy and radical external beam radiotherapy. Short, medium and long-term side effects of the three treatment options may reduce one’s quality of life significantly. (My disease was unsuited to new high-intensity-focused ultrasound, cryogenic and embedded source treatments.)

After much thought, considering Prostate Predict and comparing expectations of survival and side effects, I decided not to have treatment immediately, but to follow the conservative watch-and-wait protocol, (soon amended to active surveillance), with three-monthly PSA checks. At this point, my PSA had been quite stable around 12 -14ng/ml, once actually reducing between a pair of readings.

The Gleason Score

(scroll to reveal)

‘I definitely felt very sad at times, and angry that the disease should threaten me when I had lived my life so carefully’

Following about a year of conservative management, we noted that my PSA, after fluctuating, was rising toward 18ng/ml. Another MRI series revealed size increases in my malignancy centres, with one being close to my (apparently intact) prostatic capsule. A SPECT bone scan revealed no sign of metastatic spread. Plainly I should not delay treatment in the face of new MRI evidence, and therefore, in 2024, I started a course of radical external beam radiotherapy.

In a recent TV programme, well-known neurological surgeon Henry Marsh described the diagnosis and treatment of his prostate cancer as “a degrading, humiliating experience”. There are certainly aspects of the diagnostic procedures that could be described thus. However, I would not wish to suggest that it is in any way the fault of those who must perform those procedures to get a safe and accurate diagnosis and treatment – more that it just comes with the situation. However, Marsh also described the way he felt and reacted to the diagnosis, and I share his view of most of that. I definitely felt very sad at times, and angry that the disease should threaten me when I had lived my life so carefully. On one occasion when out for a meal with my family, I involuntarily started to weep. They were all very kind and supportive, but it illustrates that inner sadness during stress owing to serious health issues can and does come to the surface. I was also quite angry at my diagnosis, having taken care of my health, exercise and weight; my BMI being well within acceptable range. Over time I began to feel less sad and angry, but I still regarded my condition as an unfair threat to the length of my life.

My local hospital protocol comprises a short course of Bicalutamide (mine, 14 days) to prevent testosterone flare from tumour cell activity, followed by six months of slow release luteinising hormone (Prostap). Some patients were given Prostap for a year, but I never quite established why. Patients over 80 years seemed to have no radiotherapy; hormone treatment only – possibly for the rest of their lives. The administration of Prostap is quickly followed by a reduction in testosterone, with hot flushes, possible weight gain, loss of sex drive and varying degrees of erectile dysfunction. The prostate gland, also much reduced in size by the medication, ceases to produce prostatic fluid – PSA falling almost to zero.

I was booked for planning CTs in the second week of August 2024, and to start my radiotherapy course on 15 August after three months of the hormone treatment. I would have the standard dose of 60Gy in 20 fractions, finishing on 12 September.

My local hospital has a new radiotherapy and oncology department, with two linear accelerators: a new Varian Truebeam (apparently one of 28 recently installed across the NHS) and an older model retained from the old department. In the year since my treatment, another new Truebeam (funded mainly by the hospital’s charity) replaced the older machine. This features real-time beam shaping and movement compensation, reducing surrounding tissue dose.

Kenneth at home at his self-designed, self built organ console

Kenneth at home at his self-designed, self built organ console

I did not always cope easily with the radiotherapy. Sometimes I felt in danger of losing control of a full bladder, especially if equipment or earlier patient difficulties delayed treatment. In such delays, some patients might prefer starting afresh with an empty bladder, rather than wait in quite significant discomfort not knowing how long the delay might be!

I am pleased to say that my experience of all of the staff, diagnostic imaging and radiotherapy, medical and nursing, has been most satisfactory almost throughout my treatment. The radiographers were always friendly without being over familiar, and took care to ensure, especially at the start of the treatment series, that patients were aware of what to expect.

Eventually the day came for me to ‘Ring the Bell’ having completed my treatment. Towards the end of the treatment, I slowly developed several side effects from the radiotherapy. I was getting up several times in the night to empty my bladder –something which, before the onset of my disease, I never had to do. Also passing urine had become painful. Tamsulosin was prescribed and alleviated these symptoms resulting from radiation-induced tissue inflammation.

Somewhat later, on one or two days every two or three weeks, I suffered a small PR loss of bright red blood with clear mucus. Fortunately the quantity was always very small. Flexible sigmoidoscopy confirmed radiation-induced proctitis as a result of tissue exposure. Although it persisted for 10 or 11 months, it has subsided considerably in intensity and frequency, and should improve further. I bear in mind that these radiation therapy effects may persist or recur in the longer term, but they are now of reducing significance.

As many patients experience, and diagnostic healthcare staff note, procedures investigating patients’ conditions often reveal unrelated and unsuspected conditions. I should mention some of mine.

First, my MRI scans revealed adhesions around the upper lobe of my left lung. I had been aware of this since my first chest radiographs taken as part of the entry process into the School of Radiography: they were from the procedures involved in ligating my PDA back in 1949-50. I could safely dismiss it – I knew that it reduced my vital capacity somewhat, but I had had it for many decades, and I saw no reason to worry about it!

Then, there was the calcification found in parts of my coronary arterial circulation. This really was a surprise; completely unknown to me. However, when I reported having a normal ECG, neither angina nor significant breathlessness issues on reasonable exertion, it was decided that the issue didn’t require further investigation for the time being.

Kenneth at the console of a Concert Hall organ

Kenneth at the console of a Concert Hall organ

Third, it revealed diverticulosis in my transverse colon, although there was no evidence of inflammation or other disease present.

Finally, about a third of the way up my left ureter was a rather large calculus. At about 12.5mm in diameter, it was described on one report as “quite small”. The consultant urological surgeon, however, regarded it as significant – I must say, so did I! However, I expressed my view: “It must be at least 10 years old at that size, yet I never knew it was there: it never made its presence known to me!” I called to mind all those times, in my early career, when I had been called out of bed when on-call, to radiograph patients brought in, in agony, writhing on a trolley suffering ureteric colic. “So,” I continued, “can we not leave it there unless it causes me any issues?” The consultant agreed, declaring that he’d set up a plan such that if it started to give me any trouble, I could visit the A&E department and they’d contact him or a colleague to attend and do whatever seemed necessary. In the meantime, I would have an annual check KUB CT. This process worked well: in 2023 and 2024, no changes were detected. However, early in 2025 following the usual CT scan I was called to urology outpatients. The stone was making my left kidney somewhat hydronephrotic and should be removed at ureteroscopy, using laser and other tools to break it up. My case was regarded as urgent and I’d soon be called for pre-operative assessment.

A few weeks after the assessment, I attended the Day Care Centre. After preparation and discussion with the consultants’ anaesthetic and surgical, I consented to the surgical procedure as planned, with spinal anaesthesia. The procedure was successful: the calculus was broken up and removed. A ureteric stent was left in situ to protect the ureter during healing. After a short spell in the recovery suite, I was back in the Day Care Centre awaiting the return of normal sensation to my lower body. In due course sensations returned and I found that I could get off the trolley unaided, and walk to the toilet to empty my bladder. I had been told that I would experience some pain and blood in my urine for three or four days, but on emptying my bladder I was both surprised and shocked by the level of pain, which made me feel quite faint. For the next 90 minutes I painfully passed very bloody urine. Eventually I decided that my wife could drive me home while hoping I could avoid the need to empty my bladder during the 30 to 40-minute drive, which, fortunately, I was able to do.

‘The radiographers were always friendly and took care to ensure that patients were aware of what to expect’

I was warned that I would experience pain and bleeding for around three or four days, but it was actually five days before it started to ease, and more than a week before it ceased. Although not fond of taking analgesics, in what I judged to be quite severe pain, I did succumb to 500mg paracetamol before sleep – and then I was generally able to sleep satisfactorily. I was advised to remove the stent on the fifth day, Sunday, by gently pulling on the attached thread. However, I caught the thread in my trouser zip on the fourth day, Saturday, and having pulled it out by about an inch, I decided to try to remove the stent, which I did fairly easily, hoping that it would help reduce the pain. By the seventh day most of the pain and blood loss had subsided significantly. I was glad to be over that little episode!

And so now, I am 11 months on from the completion of my radiotherapy. I generally feel fit and well, although I do suffer rather more aches and pains than I did before all of this started.

In June this year, just before the removal of the ureteric calculus, accompanied by my daughter, I walked the 10-mile stage of the 2025 Annual Walk, which the local hospital-dedicated charity organises. I managed to raise almost £700, to be given to the radiotherapy and oncology department at which I was treated. I certainly found that day very difficult, but a great meal with my wife, daughter and son-in-law that evening in one of Bath’s very good restaurants helped the recovery!

So what are my conclusions? One is that you may apparently be fit and well, but you never know what is lurking round the corner. I would advise all men, after age 50, to have regular PSA tests. As we all know, the earlier cancer is detected, the better the outcomes. Tell your brothers and sons. Do not forget that damaged BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are not uncommon, and may be related not only to prostate cancer in males, but also breast and ovarian cancer in females (and possibly in pancreatic cancer, too).

I have to be honest: radiotherapy is quite a brutal method of treatment of disease. We will all look forward to the increasing advances in genetics for both diagnosis and treatment of many cancers, including those of the prostate.

Image credit: Getty Images

Read more