Digital clinical placements – the Manchester model

A blueprint for high-quality clinical training and expansion, and sustainability in healthcare in the NHS

By: Alison Sanneh, digital clinical placement faculty lead

Sheena Chauhan, digital clinical placement lead

Kirsty Marsh, digital clinical placement lead

Wesley Doherty, digital clinical placement lead

Hannah McCaughran, radiotherapy principal educator

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic served as a significant catalyst for the NHS to re-evaluate strategies for maintaining the quality of practice placement provision for both the current and future healthcare workforce. In response to the urgent need for innovative solutions to expand and enhance clinical education, a team of Therapeutic Radiographers at The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, pioneered the development of a digital clinical placement (DCP) model. This innovation, now recognised as the ‘DCP Manchester model’, represents a transformative approach to clinical education. The DCP team are acknowledged by NHS England as experts in the field.

At face value, a DCP may appear simply as an online teaching and learning experience. The DCP Manchester model demonstrates complex robust clinical education paradigms, hosted via a virtual platform. The DCP is beyond a simulated learning experience, in the same way that a traditional multidisciplinary team meeting in a physical room is replaced by a remote online meeting where the depth and breadth of the conversations remain consistent in quality and content. This transfer of ‘meeting room’ is replicated by the DCP Manchester model blueprint and essence.

The DCP Manchester model is designed to include stakeholders for that placement topic, introducing clinical conversations in real time, led by clinical experts in their field. The model supports learners to recognise clinical knowledge and deepen understanding, building confidence and strengthening capabilities across care pathways1.

Following patient and professional journeys through facilitated conversations, the model helps mirror the conversations and practice that takes place in that placement area, before the learner is exposed to patient contact. The expert practitioner explains the care interventions and their clinical decision making before carrying out that clinical procedure. We recognise that, in the physical clinical setting, much of the learner’s exposure to care is skill based, with standards of proficiency measuring the ‘doing’ opposed to the ‘knowing’. Operational pressures and limited access to experts in practice can create potential critical gaps in the depth and breadth of real-world clinical exposure and decision making. This may lead to gaps in learner confidence.

DCPs offer learners access to highly specialist practitioners in hard-to-reach clinical environments. During a DCP, practitioners may share their clinical insights with up to 150 learners at the same time while on the online platform. The size and diversity of the learner cohorts offer unique opportunities to raise questions and gain clarity on care episodes from multiple perspectives and real-world views. The model effectively supports the opportunity to consider the professionals and learners’ lived experience, and how these experiences could be used to develop individualised consideration for patients and their families or carers. Patient stories are integrated into the curriculum content, with further dialogue from the experts and learners to jointly explore. Guided by clinical educators, the clinical experts support learners in making sense of care episodes and the potential impact on patients, relative to their professional practice.

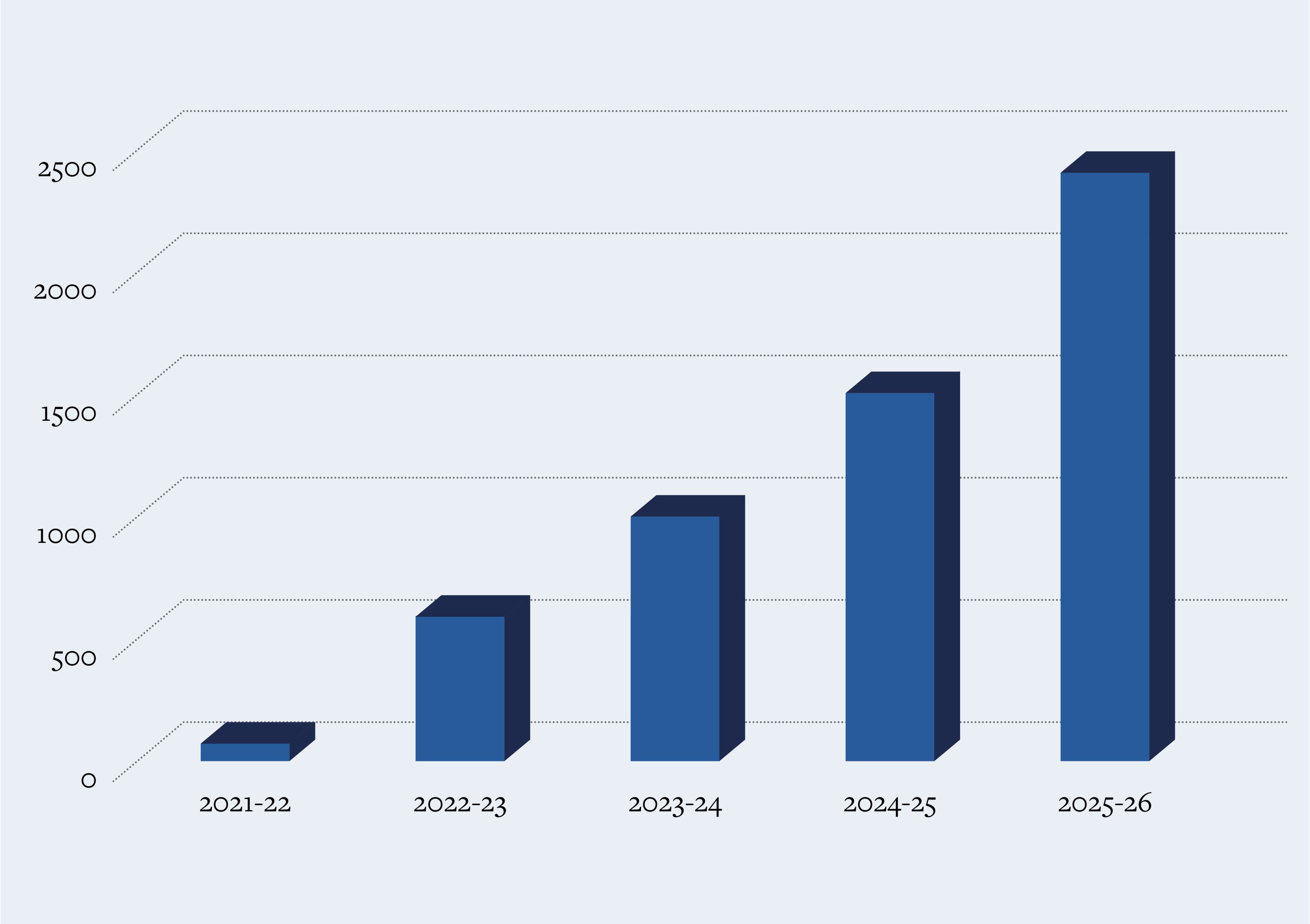

Scale of DCP Manchester model 2021-25

Scale of DCP Manchester model 2021-25

Over the past five years, the DCP Manchester model has received significant investment. It has undergone rigorous internal and external evaluations, leading to optimisation to ensure high-quality clinical placement experiences across pre-registration and registrant workforces. Quality measures are undertaken against policy matrices, including the NHS England Education Quality Framework (2021)2, the NHS Workforce Educator Strategy (2023)3, the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan (2023)4 and the Safe Learning Environment Charter (2024)5.

The design and delivery of the DCP Manchester model is complex and multifaceted. This article offers readers insights into the blueprint of the model, illuminating the importance of DCP components that are tailored to frontload learners with knowledge, skills, capabilities and confidence to make a difference in their clinical and technical care delivery in practice.

Evaluation

It is critical that the DCP Manchester model can demonstrate the value it may add to clinical teaching and learning across health and social care, including radiography.

The model has received peer review by experts in clinical practice and learner outcomes have been evaluated by professional regulators, including the Nursing and Midwifery Council. The review has identified that it is an innovation closely aligned with NHS strategic objectives and regulatory frameworks, which expands placement capacity and enhances digital competencies, and provides a financially robust learning solution with operational feasibility. The DCP Manchester model removes pressure in the physical clinical environment while providing learners with unique access to experts in their field and across healthcare systems.

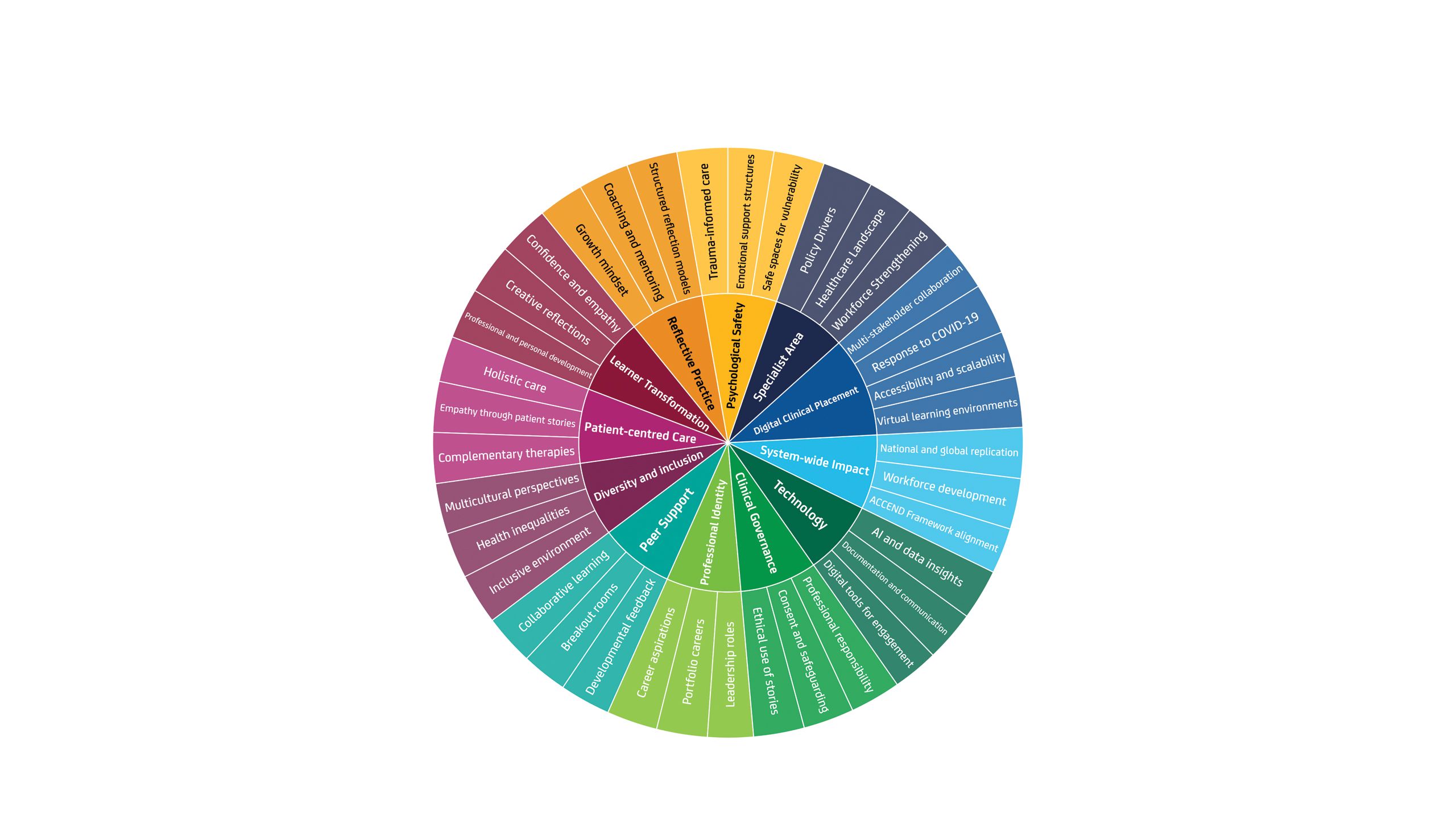

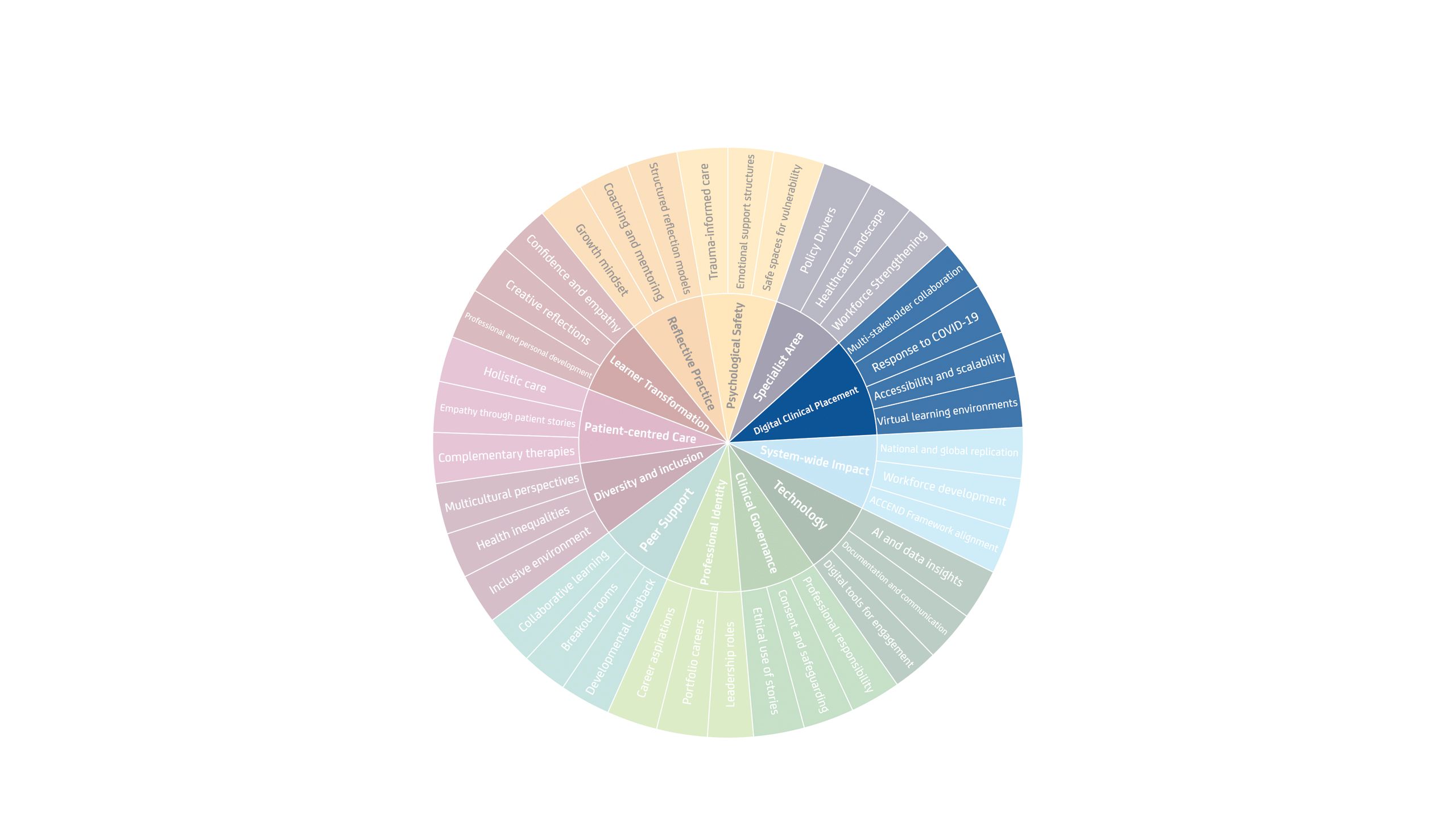

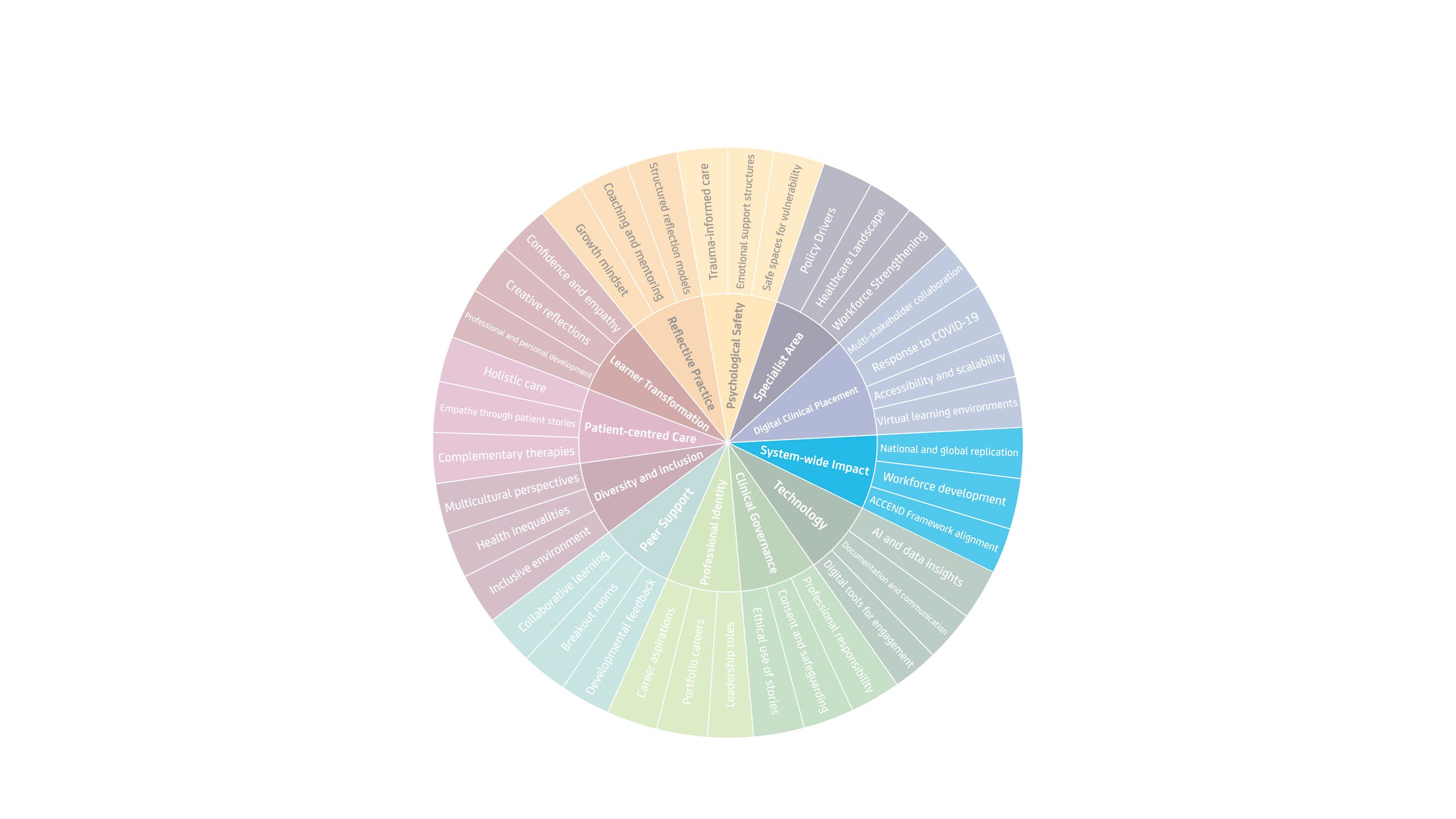

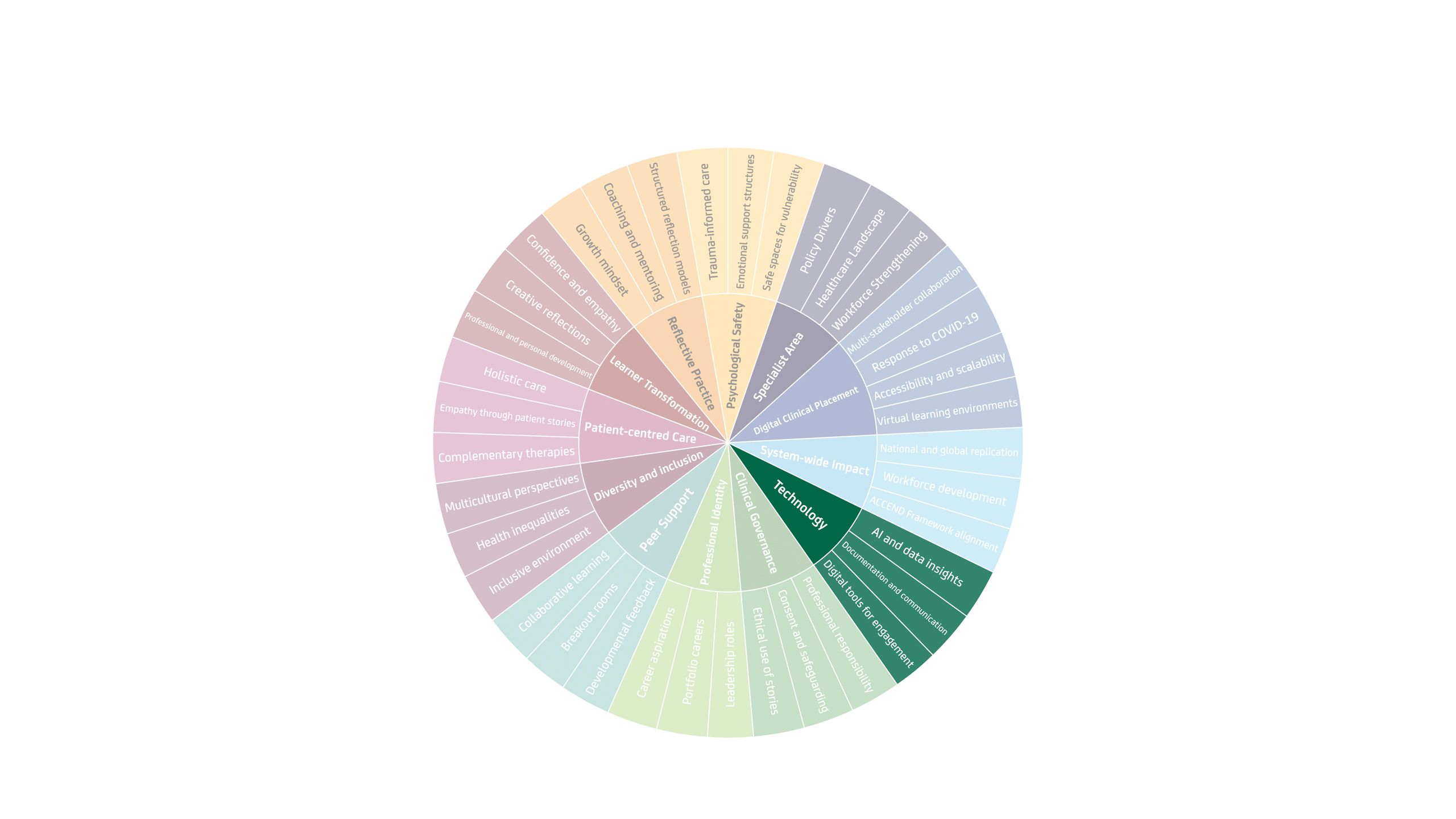

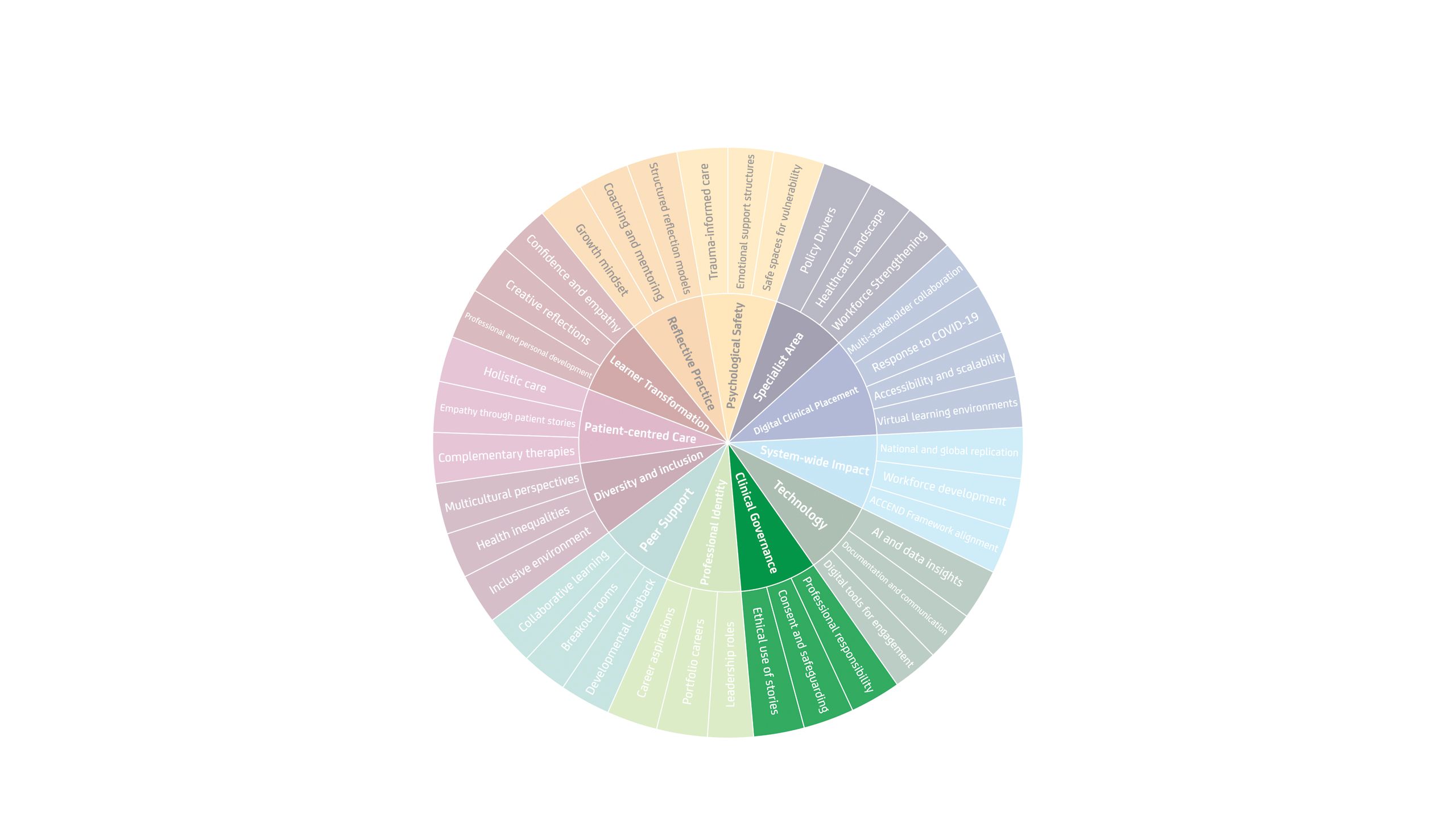

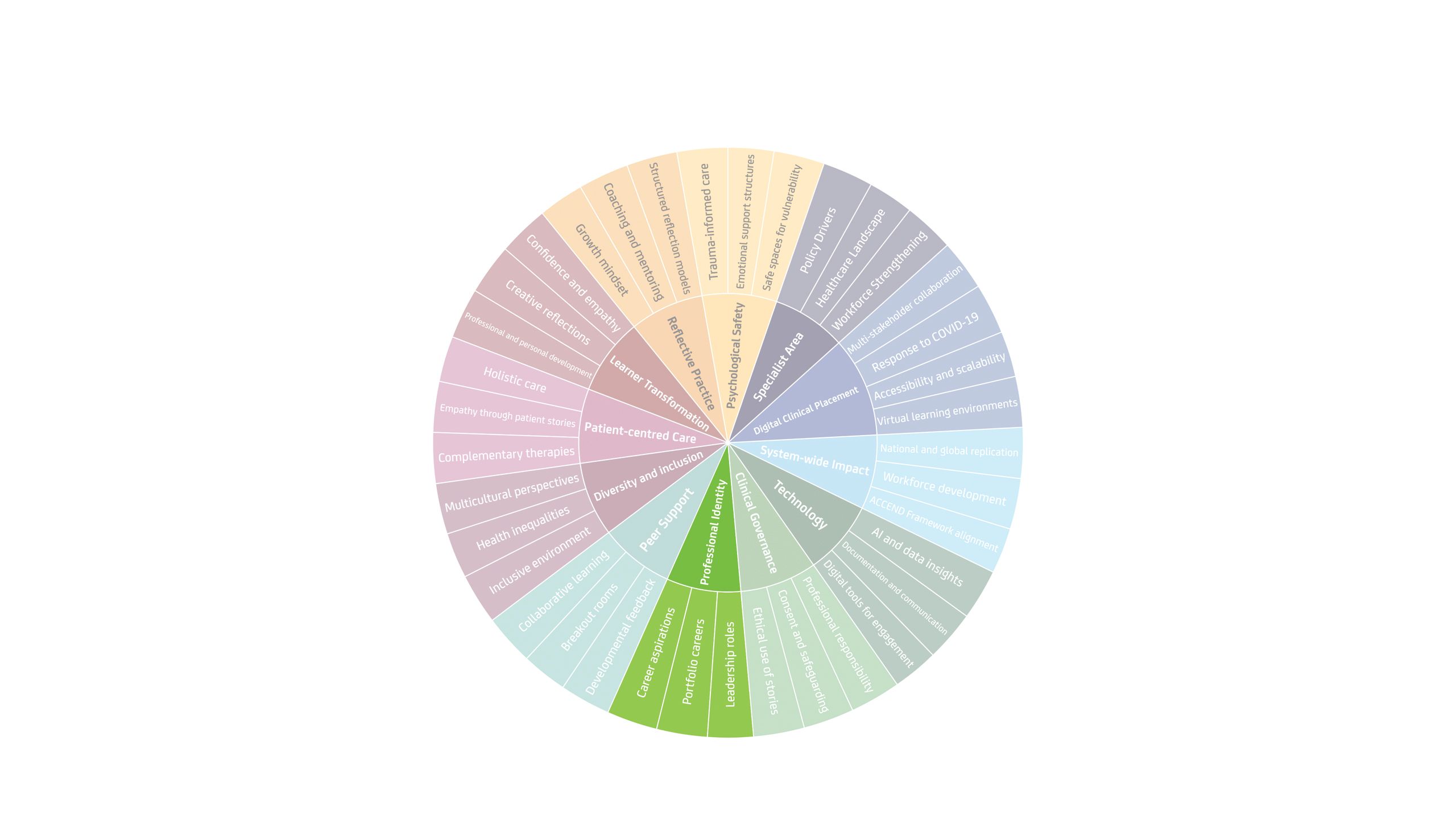

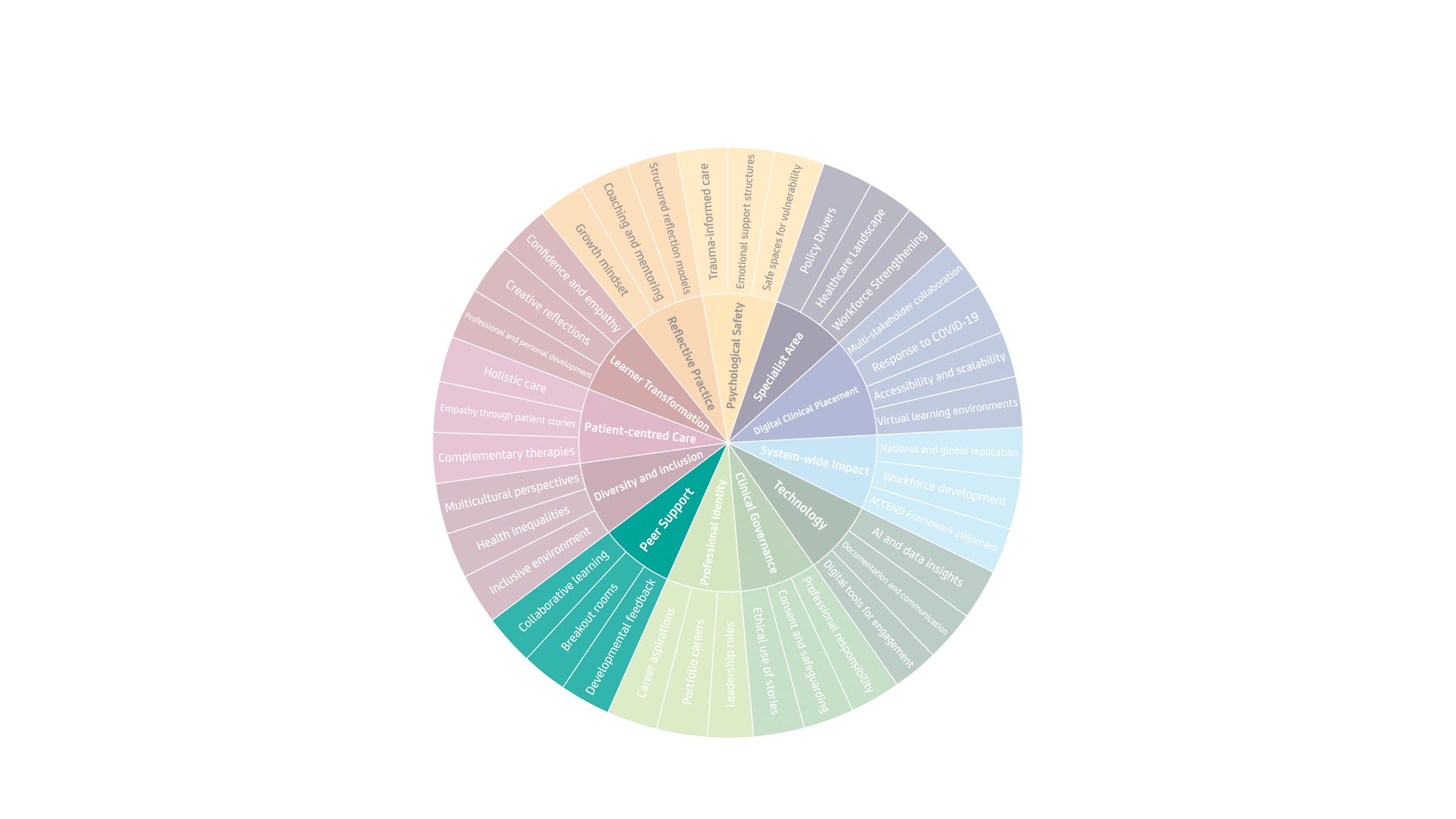

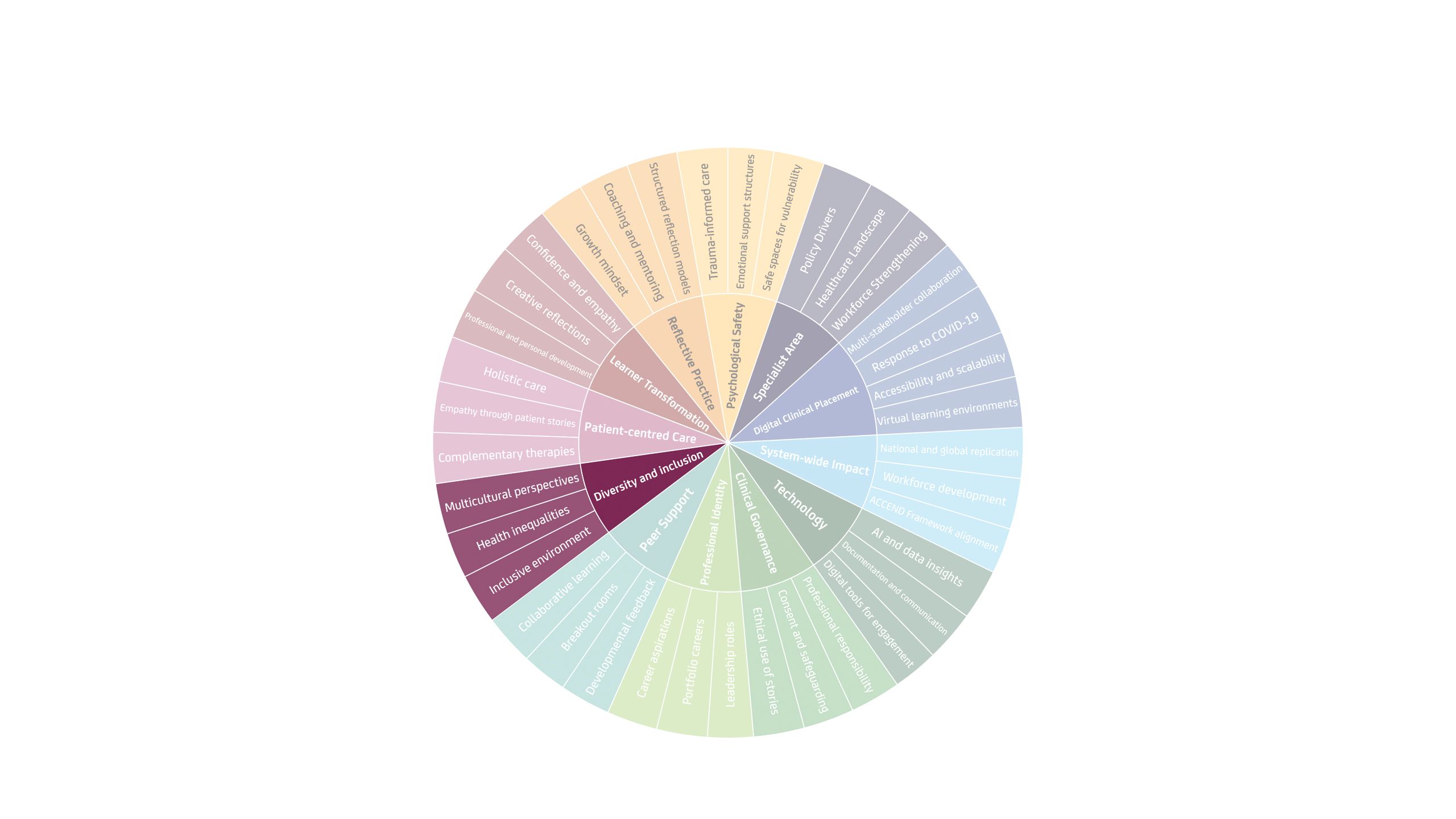

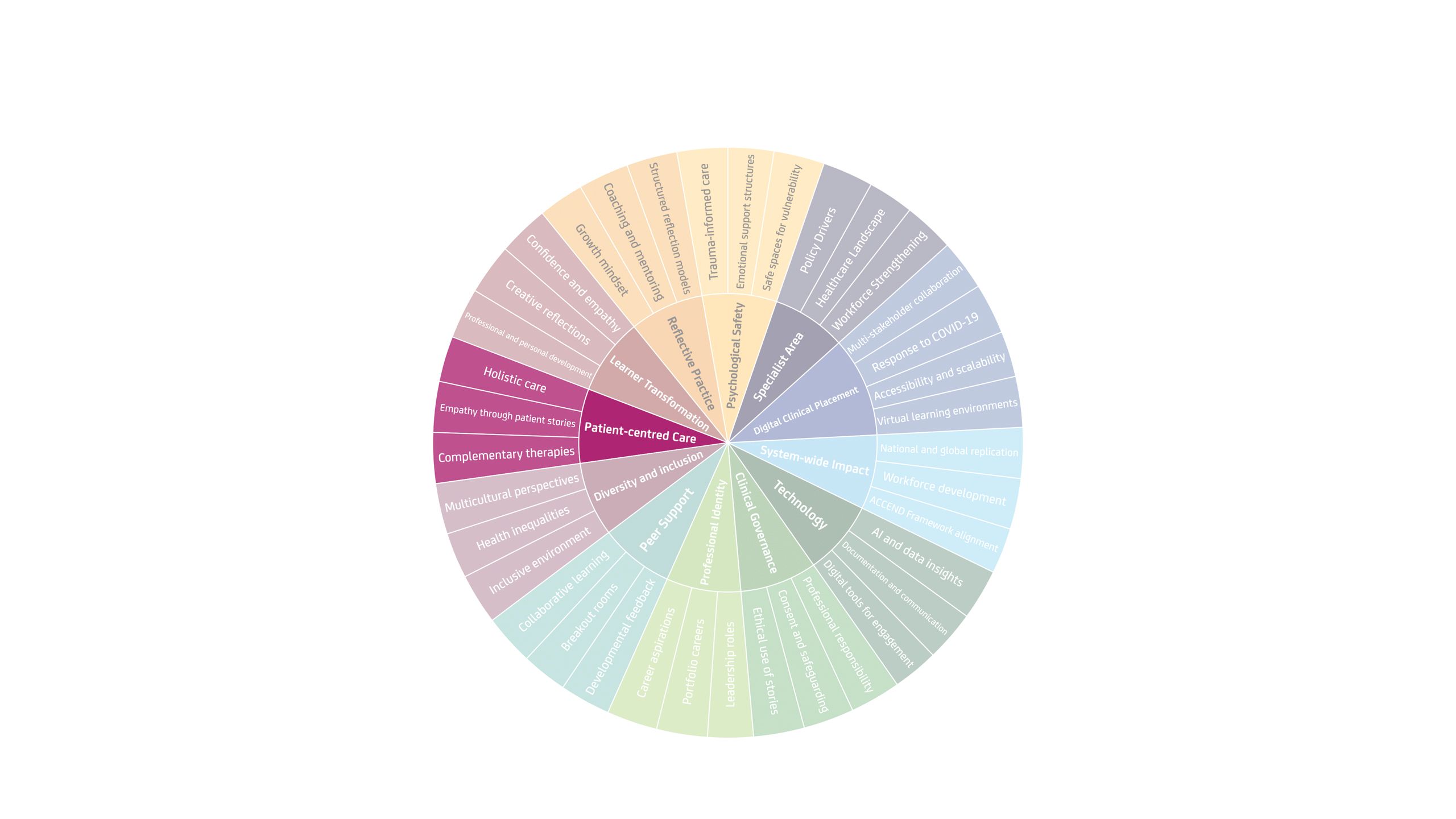

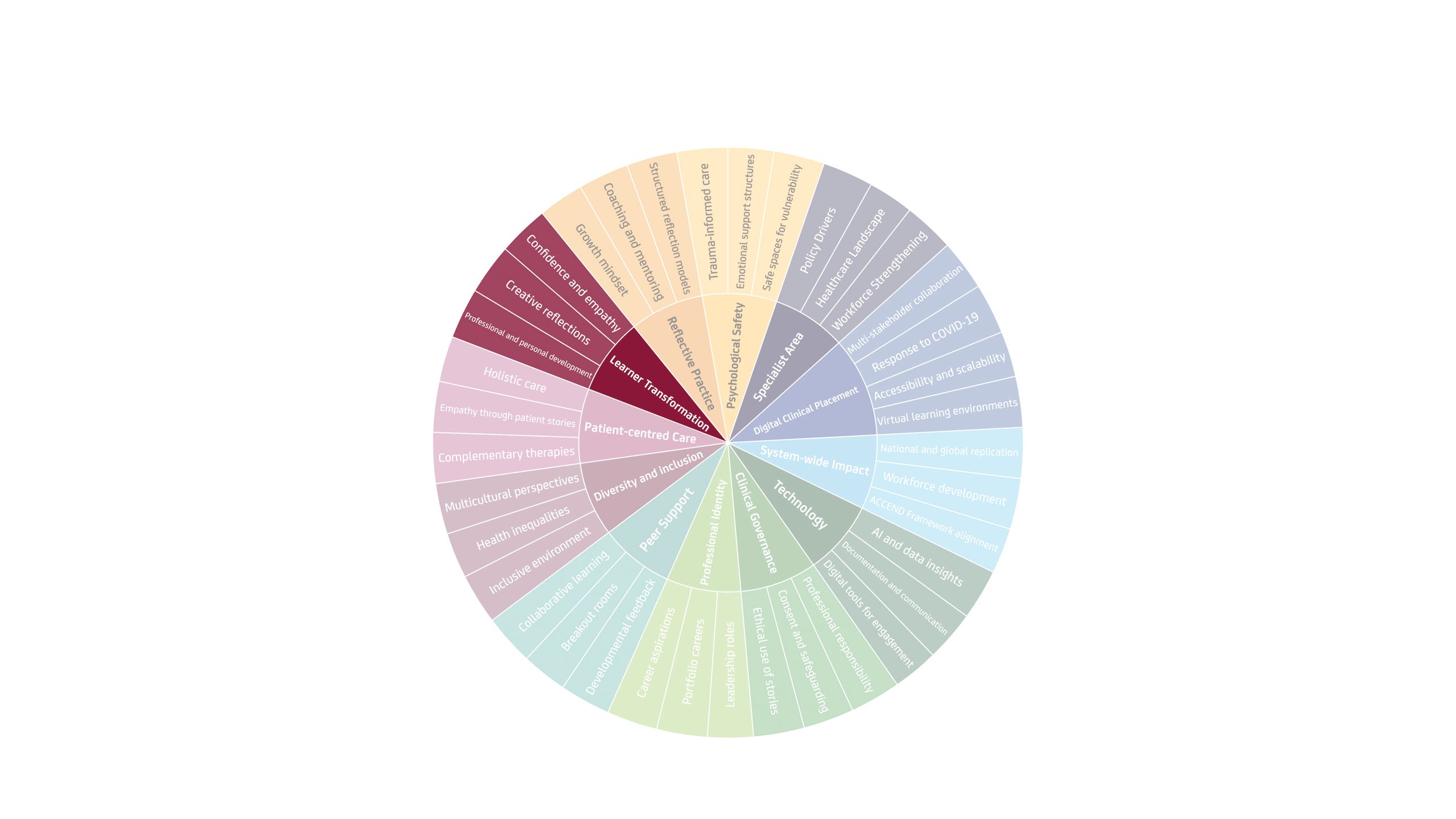

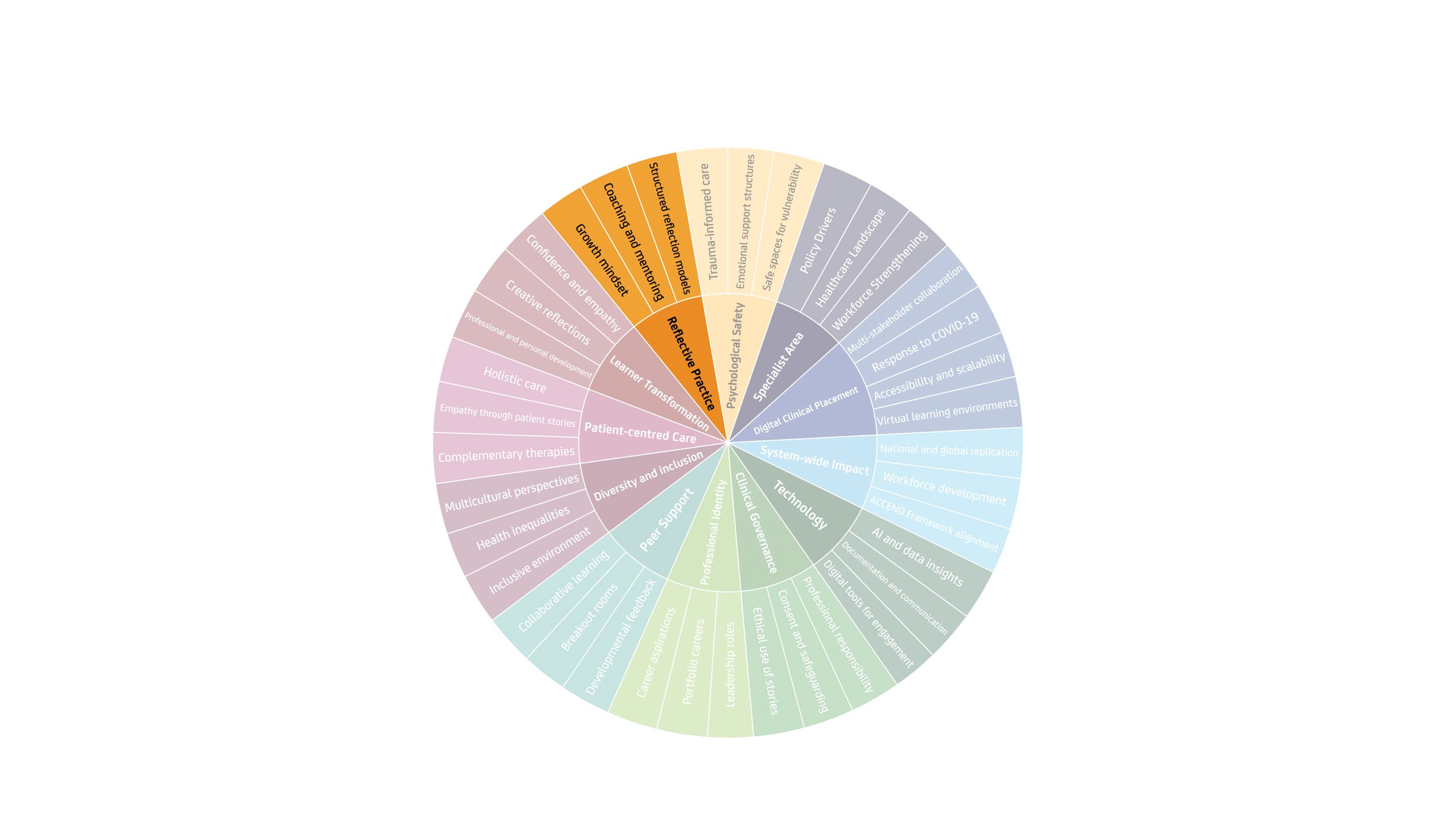

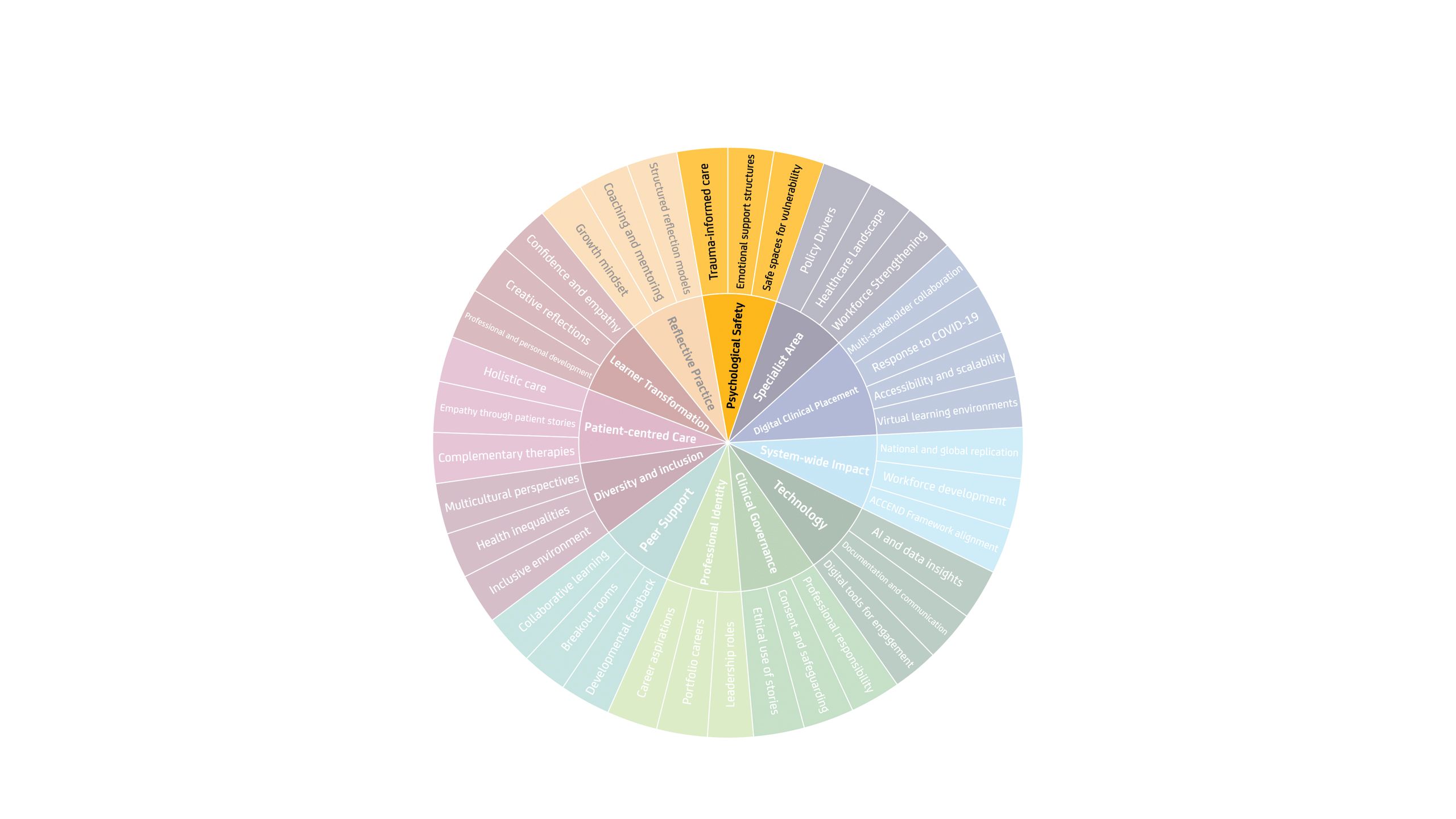

Preliminary impressions have identified 12 core components that must be in place to complete the DCP Manchester model blueprint. These components have been identified through evaluating formal and informal interview data from 40 stakeholders, including internal DCP contributors, higher education institute partners and learners. Themes have also been identified, using artificial intelligence, from more than 2,000 reflective reports from learners, to inform the core and subcomponent criteria. Two years of internal and external formal research analysis is currently underway, with a view to be published this year, adding to the rigour of the DCP initial impressions.

The 12 components of the DCP Manchester model

Component 1: The specialty

When the DCP team are invited to design and implement a DCP in an area or for a topic, stakeholders ask fundamental questions, including:

- What are the policy and professional drivers informing the agenda?

- What is the topic and why is it important to address and strengthen this regarding patient and community outcomes?

- What are learners already exposed to?

- How would a DCP support existing curricula and synergise with wider clinical education offers?

- Who are the key stakeholders and wider contributors?

- What is the expected outcome from introducing a DCP?

- How can the DCP be evaluated, scaled and sustained?

For example, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, provides a national proton beam therapy clinical service. A key policy and professional driver is that our future Therapeutic Radiographer workforce has a comprehensive understanding of this modality to ensure they can provide accurate and relevant information to patients in their care. This includes eligibility and any advantages of proton beam therapy and comparison to conventional modalities, in a measured way. There is a need for a Therapeutic Radiographer to be competent in understanding radiotherapy modalities in their professional sphere.

A further driver includes exposure to proton beam therapy as a career opportunity, cultivating the future workforce pipeline. The proton beam therapy DCP provides a systems view of radiotherapy services, including commissioning, multi-agency systems-level care and collaborative services, wider exposure to paediatric care and modelling Therapeutic Radiographers’ adaptability and careers portfolio. A national DCP ensured all pre-registration learners across the UK had the opportunity to learn about proton beam therapy from clinical experts, avoiding inequalities in accessible clinical education. The digital offer ensures learners do not have to travel, reducing placement costs to the learner and offering them time to balance responsibilities, such as caring or employment commitments.

Component 2: The stakeholders and accessibility

DCPs require multi-agency collaboration. Key stakeholders include professional and regulatory bodies, higher education institutes, charities, clinical experts, service users, learners, clinical educationalists (DCP experts) and alliances associated with the subject matter.

DCPs are maturing and are beginning to be written into curricula for programme approvals. Professional regulators are required to understand DCP outputs and to agree the model as contributing to learners’ clinical hours. The Nursing and Midwifery Council, following a midwifery DCP pilot, evaluated output and recognised the DCP Manchester model as a high-quality clinical teaching and learning experience that aligned with clinical practice. This is an important message to approval panels across multi-professional provision.

Higher education institutions require assurances of high-quality clinical teaching and learning, supported by environmental audits and continuous performance reviews. Aligning with the NHS England National Learning Contract, placement provision is secured with local, regional and national agreement of learner numbers under the DCP provision supporting scalability and sustainability.

Component 3: Systems influence and impact

Clinical experts, charities, service users, learners and clinical educationalists shape DCP curricula. Informed by policy, healthcare trends and inequalities, contributors work in collaboration to respond to individual and community needs. Experts in practice are invited to peer review DCP programmes and map activity to professional standards of proficiency and associated national health and social care frameworks.

The blueprint of the DCP Manchester model demonstrates the resources and infrastructure required to complete this educational paradigm at scale. If the DCP Manchester model is the ‘cake’ that provides consistent quality and assurances, the programmes introduced are the ‘added ingredients’ – offering DCP in different flavours to meet the appetite of the national health and social care drive.

The platform provides unique insights and opportunities to guide curious conversations.

Component 4: Technology

The DCP model is hosted on a Microsoft Teams independent domain, which replicates the NHS digital tenancy. An independent domain overcomes obstacles of learners requiring an NHS email account and allows international learners to access their placement from outside of England. Utilising the same software as NHS users supports future workforce in software features that will be required in employment, and builds technical awareness and confidence.

Learners are required to have access to functioning cameras, microphones and headphones to facilitate engagement in the learning environment. This can introduce challenges related to digital poverty, and the DCP team works closely with higher education institutions and learners to address this.

Clinical education methodologies are reinforced on the platform, encouraging and developing independent clinical reasoning, self-awareness, self-regulation, emotional intelligence and reflexivity, all of which cannot be artificially generated. The DCP team leans into the potential of AI and seeks to explore where value is added and where it can stifle professional maturity. AI applications include supporting the structuring of personal and professional learner reflections and evaluating large quantities of data to feed back the impact of teaching and learning for subject matter experts and wider audiences.

Component 5: Clinical governance

Clinical governance is a core component of the DCP Manchester model, encompassing safeguarding, ethical approaches to storytelling and the sharing of sensitive experiences, data protection, informed consent and rigorous data collection and evaluation. For example, learner cohorts accessing the DCP platform typically range from 50 to 150 participants, with programme correspondence cross checked against unique learner ID codes. Registers are maintained using only the minimum necessary personal information.

Patients who generously share their personal care experiences are provided with time to decide what they wish to share, provided with written consent to sharing and are made aware that they may withdraw consent at any time. Patients sharing stories are required to be under the duty of care of NHS organisations or affiliated to a charity, in the event that trauma is reintroduced when storytelling.

The DCP team pays attention to the learner and subject matter experts’ safety needs. Stakeholders are encouraged to share their own stories, whether personal or professional. They become the expert through experience and require the same level of due diligence of care as patients.

Component 6: Professional identity

The DCP model offers multi-professional clinical environments where every professional voice matters. Learners work with colleagues from other universities, professional disciplines and different backgrounds. Learners may be at different stages of their formal training and have different life experiences. Each learner can hear from legacy professionals, sharing career insights and portfolios. It proves key that clinical conversations are relatable to one’s professional identity while sharing important insights and perspectives from wider world views. A feature of the DCP Manchester model is to showcase diverse and rewarding careers, demonstrating to learners their potential reach and rewards in health and social care.

Component 7: Peer support

Peer support, breakout room collaboration, peer feedback, socialisation and celebration are key features of the DCP. Across one and two-week placements, peers form their own clinical team and take responsibility for individual and team effectiveness. Learners experience a range of emotions, navigating through cold dysfunctioning teams, cosy teams, through to highly functioning teams. They benefit equally from developing reflexivity and learning to balance the social and process aspects of effective team functioning. Individuals naturally adopt roles within a team but may need to adapt these roles in response to the team’s needs. They remain responsible, accountable and empowered to influence and shape team dynamics and manage conflict without external interferences. Learning and leadership development emerge organically through the DCP and are consistently recognised by learners as impactful at the conclusion of the programme. Learners benefit from rich, peer-led 360-degree feedback that validates their contributions and development.

Component 8: Diversity and inclusion

Diversity and inclusion run as a golden thread throughout the DCP Manchester model and are actively implemented, reviewed and monitored. Public, patient and community involvement is central to its development, with a clear commitment to an inclusive workforce that reflects the populations served. All contributors – including patients, subject matter experts and learners – are encouraged to value difference and consider how lived experience shapes perspective. This includes attention to identity and demographics, health inequalities, socioeconomic factors, sexual orientation and gender, intersectionality, respect, dignity, accessibility and cultural competence.

Component 9: Patient-centred care

A clear line of sight to patients and their families runs throughout the DCP Manchester model. Learners are supported to recognise that how they engage in placements reflects how they care for patients, reinforcing professional responsibility, responsiveness and attention to what matters most to individuals. The learner emerges with a deep sense of compassion and empathy, appreciating that, as professionals, we treat people, not disease.

Component 10: Learner transformation

Staff delivering the DCP Manchester model, including subject matter experts and clinical supervisors, are formally trained in coaching and have access to coaching supervision. Using a coaching framework, the DCP provides an individualised approach that encourages authenticity, appropriate vulnerability and supported adaptation and change.

Robust DCP evaluation demonstrates significant improvements in learners’ confidence, empathy, creativity and personal and professional development. Self-assessed leadership capability shows statistically significant increases across learners, with qualitative and quantitative evidence confirming transformational impact across large, multidisciplinary cohorts.

Component 11: Reflective practice and reflexivity

Reflection and reflexivity underpin professional self-regulation, adaptability and continuous improvement. Through a coaching framework, learners develop these skills as core clinical competencies, supported by models such as Driscoll’s reflective model6 (‘What? So what? Now what?’). The DCP Manchester model builds confidence, capability and commitment, enabling knowledge transfer and meaningful behavioural change. Each learner is supported by an independent, trained clinical coach who recognises contributions and offers constructive feedback. This coaching approach helps learners identify and address factors that may hinder care, empowering them to make informed choices to maintain or adapt practice in the best interests of patients and their families.

Component 12: Psychological safety

The DCP Manchester model commits to all stakeholders feeling seen, valued and psychologically safe. This philosophy starts from the earliest contact, aligning expectations through building relationships and mutual contracting. Key to this safety is clear boundaries, expectations, resources and rewards. Language applied in the DCP forums is clean, aims to be non-judgemental, reduces bias and avoids power and positionality. The DCP model prides itself on creating a psychologically safe teaching and learning environment that acknowledges people and their lived experiences and worldview. It shows genuine concern and consideration for all participants as a global professional family, with one common interest to improve clinical outcomes and care experiences for patients.

Scale and sustainability

Pre-registration courses, including radiography programmes, require learners to secure a dedicated number of clinical learning hours. Our workforce has a duty to ensure these hours are purposeful, high quality and rewarding to learners, who will then be adequately prepared for future practice.

The DCP Manchester model is approved as clinical practice hours by professional regulators; this is a key message to stakeholders, including learners, that teaching and learning in this virtual environment is endorsed by regulators and holds equal merit to physical or patient-facing practice learning. The NHS England Education Contract awards a learner tariff for clinical simulation or practice placement hours. This tariff generated from hosting learners enables scalability and sustainability of the DCP portfolio. In 2021, The Christie Hospital NHS Foundation Trust designed and implemented its first DCP on the topic of proton beam therapy. Therapeutic Radiographer learners across universities in England benefited from access to this specialist modality placement. Building on this, NHS England invested further in the DCP design. 2022 and 2023 saw the implementation of two additional DCPs, Specialist Radiotherapy Modalities for Therapeutic Radiographers, and Oncology Pathways for Nurses and Allied Health Professionals. Five years on, DCP investment has expanded across diagnostic radiography programmes, midwifery, global health, multi-professional preceptorship and community practice.

Looking towards a sustainable future – the vision and affirmations

The NHS faces significant workforce challenges in meeting patient and community needs over the coming decade, while reducing health inequalities and improving care outcomes. To respond, the future workforce must be able to adapt, evolve and transform within an increasingly technology-driven healthcare environment. This requires elements of workforce development – including knowledge, clinical capability, wellbeing and professional growth – to evolve and transform in line with needs.

Over the past five years, the DCP Manchester model has demonstrated a proven innovation in clinical education, complementing theory and skills-based learning with expert-led, real-world clinical experience. The model is agile, overcomes geographical and capacity constraints, and reinvests all income directly into workforce development. It ensures that high-quality clinical education is sustained and keeps pace amid competing system pressures.

References

- Sanneh, A. and W. Doherty. Creative provision of radiotherapy clinical placements. 2022 01/09/2022]; Available from: https://society-of-radiographers.shorthandstories.com/creative-provision-of-radiotherapy-clinical-placements/index.html.

- Health Education England. HEE Quality Framework. 2021 [cited 2021; Available from: https://nshcs.hee.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/HEE-Quality-Framework-from-2021.pdf.

- NHS England. Educator Workforce Strategy. 2023 23/08/2024 07/01/2026]; Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/educator-workforce-strategy/.

- NHS England. NHS Long Term Workforce Plan. 2023 07/01/2026]; Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-workforce-plan/.

- NHS England. Safe learning environment charter: what good looks like [Internet]. London: NHS England; 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 14]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/safe-learning-environment-charter-what-good-looks-like/,

- Greene, J. Driscoll model of reflection. 2024 07/01/2026]; Available from: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/health-and-medicine/driscoll-model-reflection.

Read more